Margot Farrington, The Blue Canoe of Longing, Dos Madres Press 2019. Available from Dos Madres and Amazon

Margot Farrington’s Blue Canoe is an unqualified pleasure. Every poem in it is readable, well-worded, and, be it narrative or descriptive, the meaning is always clear. It’s like looking at paintings by someone who can really render, and does, canvas after impeccable canvas.

Modern poetry is all too often an evocative chaos from which meaning occasionally peeps. I know it’s a well-respected style, but not one I can long enjoy. For me, it soon seems a long slog through the murk , waiting for the prize of a few dazzling lines.

Margot Farrington is an intensely welcome dissident. And hers are not the empty lucidities of the MFA trained, or the pessimism and conventionalities of the New Formalist, but well-wrought polished compositions animated by a sense of wonder.

We are fortunate to be able to reproduce in full four complete poems from this book , so I will mine other poems from this collection to illustrate the points made here.

Farrington is especially strong when she presents landscapes, grand or petite. These she describes in phrases where levels of meaning effortlessly combine and coincide so everything seems meaningful as if seen in a dream.

From Conception in May,

I must have known May was the only month I

stood a chance to be conceived. People’s coats

came off, the lindens lifted bicolored bouquets

while the mockingbird married ecstasy

on the highest aerial of the neighborhood.

Laundry flirted along the lines—a pair of panties flew off

while the rest swelled with innuendo.

The language is so exquisitely select you can feel its texture; it’s hard not to read it aloud—and if you do, it’s like running your fingers over a sculpture or a seashell to really exult in those smooth contours.

From Highland,

Thistle on the hill. Purple too, the evening cloud.

The sunrise orange, the fields orange, the window glass

licked orange then gold, licked clear as glass again.

This inwoven musicality, is something I associate with poetry written by women. I realize that I’m on sensitive ground here, liable to draw fire from all sides. Now I’m not saying this is a characteristic in all poetry by women or in all the poems by any given woman, but it is something I have seen brought to an unusual level of perfection by women. Men tend to choose words that get the job done with eloquence (fluency, power, and appropriateness). What Donne calls “my words’ masculine persuasive force.” Men love nothing better than a phrase that rings out brief and clear with oratoric power. Not to put too fine a point on it, boys like things that make a big noise.

At the risk of seeming to merely refurbish clichés, women more often take pleasure in dressing their thoughts, with everything that assonance, alliteration and unusual words can add to the palette. It’s something I have always loved in the Sylvia Plath, and obviously in Margot Farrington. A very bouncy example of this richness is perhaps Christina Rosetti’s Goblin Market. Not that men can’t do this and just as well—especially the more feminine Romantics, like Keats—but it’s not their typical choice. This richness of language gives women’s poetry a special emotional warmth.

One will not always find this particular strength among the canonically great women poets in English: Dickinson, Barrett-Browning, St. Vincent Millay, not even Louise Bogan or Amy Lowell—because, it appears to me, they were all trying to write like men. They took great pains to set forth suitably deep ideas with proper logic, and demonstrate flawless mastery of form, in fine, to show they could compete with the boys—and the result was too often eloquence. In the case of Dickinson, this led to so cruel a corseting of thought that (as the punctuation attests) the verses only emerge as a series of gasps.

For me, women’s poetry in English begins with Plath and those wonderful first two books by Anne Sexton—before quick fame had her churning out mediocre chap-books to maintain her one-woman circus of symptoms.

But back to Farrington. She absolutely has the textured density of language, charged with emotional depth, that women seem most able to manage. Another notable feature of her verse is the close and precise observation of physical things. This is of course part of modernism, and is not gender specific. The Imagist poets are the pioneers here. But Farrington, like Plath, infuses material details with an emotional charge.

It’s instructive to compare the style of that great master of physical description, Allen Ginsberg. His language was as richly textural as can be, but he wasn’t primarily concerned with beauty—modernists aren’t. Ginsberg was interested in poetry as a vehicle of naked truth, and his language favors precision a little more than musicality . Farrington takes the opposite approach, which makes her truths attractive. Ginsberg went for vividness, so exactingly and intelligently that the effect can even be a little clinical.

To make a general comparison of the epic and prophetic Ginsberg with the intimate and miniaturist Farrington would of course be silly. I only contrast here their different approaches to Imagist descriptiveness. Farrington communicates how everything looked, smelled, sounded, tasted—in a way that musically includes how she herself felt. She emotionally takes us into her curated personal landscapes, perfect worlds, lucent and engaging as a tidal pool, or a bell-jar still life.

As for the inhabitants of her perfected realms, she describes people and living things with playful, Ovidian wit,

From Wine,

So I had a glass or two.

Soon I was swaying like a cobra,

not to music others could hear.

To my mind, her finest poems are those set in nature, which show us scenes of jewel-toned vividness, such as we find in the poets of Alexandria (Callimachus and Theocritus, and Virgil where he imitates them). —or, to give a reference that may be easier to catch, in the Pre-Raphaelite painters.

Farrington’s book is a wonderful treasury of images, vignettes, situations and stories, all lapidary in language and cinematically realized, in fine, she gives us lucid dreams. [MF]

Anne Myles, Late Epistle, Headmistress Press 2023, available from Headmistress and Amazon

After a decades long retirement from writing poetry—which not surprisingly began with graduate school (the grave of so much imagination!) Anne Myles took an early retirement and recovered at once her power to create. Late Epistle is the first-fruit of this resurrection, and it has all the excitement of a manifesto—along with a very winning humility about just what it’s manifesting—a memoir, a credo, a remarkable book of poems. (We are fortunate to be able to give several of the poems in full here.)

The book as a whole is dedicated to her parents, and opens with the splendidly ominous opening Bane, a boding of her own her doomed sense of family, heredity, and place.

Part One is devoted to recollections of childhood, parents and relatives, which reach crisis in accounts of her parents’ dementia. This final horror, though delicately expressed, makes for uneasy reading. What can one place as the coda of such an account? Myles offers “The Swims,” an elegy which gives meaning and completeness to the history, with a water metaphor she has been developing throughout the section, most fully in the poem “Fishing in Childhood.” This lake with its symbolic depths, and the figure of herself as an only child curiously comforted in the undisturbed immensity of her own aloneness, takes us to a place of painful awe, like a Bergman film or a Munch painting.

Part Two describes her adulthood, and unambiguously expresses her lesbian identity. The poem “What Is” does so with particular poignance. This section abounds in archetypal psychological situations: horseback riding, painting a O’Keefean flower, pondering John Donne’s eroticism, a crush on an older girl. “Luxe, Calme et Volupté” is a little masterpiece. It describes a picnic idyll, modeled on a Matisse, which drolly unfolds difficulties worthy of an Ovidian nymph. The author is caught between a man whose love she can’t really reciprocate and a woman who can’t reciprocate hers. Part Two is a series of poetic monologues with enough self-revelations to satisfy the dramatic cravings even of our present “great age of television.” The section ends with poems to a woman in upstate New York, which exemplify one Myles’ leitmotifs: painful estrangement resolved into poetic longing. The sentiments are unquestionably authentic, and the poems have a harrowing beauty.

These landscapes of longing are exalted into otherworldliness by a sense of existential solitude—a note struck several times in the poems of childhood, but now expressed with such vast clarity it rings out like a knell.

The parade example here is “The Midwest of Grief,” immediately followed by “Red Door,” a vision of an unduly normal life which opens onto the world of the dead in the final lines. This is a theme that recurs throughout the book,

how something never planned would open wide,

immersing me within the stinging cold

of some foreign, deep, and penetrating element. (“Immersion”)

Death, madness, isolation from people, and transfiguration (as in the poem, “My Abstract Sublime”: the joys of emptiness—so vast, a world of blue.) —these are initiatory motifs, and any shaman from an archaic society would know exactly what she means. Whether Myles herself understands the labyrinth she is threading with these allusions is a question worth pondering. But, conscious or not, these archetypal images give the book a singular power.

The third and final section brings us to the present, the Vita Nuova that began with the realization that the groves of academe are, finally, Persephone’s. As she already tellingly noted in “The Crack,” which describes the life of a graduate student,

I knew one thing at least,

how to contain myself.

“Waste Places” and “The Flash” amply fulfill the promise of what has gone before—a personal illumination, to which I cannot do justice in a summary.

What an extraordinary Late Epistle this proves to be, a real message in a bottle from a far explorer! The book is beautifully produced, with a cover painting that could not have been better chosen. If you haven’t already completed your Christmas shopping, we wholeheartedly recommend this book as a rare gift for one’s more intelligent friends.

[The publisher of this book deserves a word. Headmistress press is run by Mary Meriam, in whose remarkable online magazine, Lavender Review, we first found the Anne Myles’ poems. As the only magazine devoted to lesbian poetry and art, it would be remarkable enough, but the quality of its content makes it particularly worth a visit. Meriam, herself a notable poet, was inspired to these literary ventures by Lillian Faderman, the great and ground-breaking historian of contemporary lesbian history. ]

Jean Lorrain, Blood of the Gods¸ translated by Jacob Rabinowitz, Snuggly Books, 2023. Available from Snuggly Books and Amazon

I first became aware of Jean Lorrain, as most folk of my generation did, from references in Philippe Julian’s Dreamers of Decadence. Fairly recently, a number of publishers, began to make his novels available in English. Particularly Snuggly Books, which is known for their line of translations from the French Decadence, and whose catalogue is well worth a visit. Lorrain’s stories are delicious, impossible bonbons of lurid fun, like a Ken Russel movie—though without the film-maker’s deliberate humor. For a classy horror story, Lorrain can’t be beat.

He, however, always thought of himself primarily as a poet—an opinion never shared by the French reading public. And it’s rather a pity, because he almost was a wonderful poet. He had the verbal magic, the imagination, the literary culture. All he lacked was a good editor.

In French, his problems, all of them quite soluble, are obvious. He repeats favorite words like “pale” till you want to smack him. He ruins perfect stanzas with desperately seized-upon rhymes. There are simple continuity problems: someone is described as towering and then as crouching, apparently simultaneously.

A good editor would have made Lorrain a very creditable poet. No doubt some of his friends made suggestions. But Lorrain was always impetuous and rather too full of himself. His overwhelming self-confidence was a spectacular asset in his career as a public intellectual, larger than life and twice as scandalous. But when it came to his cherished poems, he’d brook no criticism. Any change would rob the work of his “voice.”

Rabinowitz as translator has done perhaps the greatest service ever rendered by a living author to a dead one. He’s cleaned up the text, with incredible sensitivity, and brought out the wonderful poetry in Lorrain’s work. I expect this book will make Lorrain’s reputation in English, and baffle the French who have the disadvantage of reading him in the original.

As to the content: there are a number of short stories told in luxuriant narrative verse, set in the Romantic Middle Ages of Lorrain’s dreams. Then there are brief Arthurian poems, vignettes that rank with the finest passages of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, and surpass it in their gem-like Pre-Raphaelite perfection. Arguably best of all are the final series of poems, descriptive of the perverse Greek gods. I will quote the opening poem of this section, Ephebes, which should suffice to decide that this book is indeed for you, you sad, wicked man.

Risen from the long-dead centuries

like a strangely troubling perfume,

these phantom beings—like slender, naked

archangels; without clothing, without names,

without a gender, dancing before the shrines

of less expected gods.

Creatures of filth and splendor,

lips shaped for forbidden kisses,

beings of the sewer as much as of the temple—

you despise them? They retaliate

with demons’ triumphant laughter!

Sculpted on Grecian pediments

(like the frontispiece of an erotic book),

I have sketched them in these pages,

crowned their brows with lilies;

for me, these creatures have their own eternity.

Beautiful, stupid, tragic

figures in the antique style,

boys, but in subtle, disquieting ways

more feminine than girls.

It’s a magnificent book, and anyone who has a taste for Symbolist and Decadent art is sure to love it. More importantly, this is one of the finest modern works of male homosexual poetry predating Ginsberg. Those who admire the dignified Calamus section of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and the refined erotic wit of Verlaine’s Hombres will be glad to add this volume to their collection of worldly books.

Federico Andahazi The Merciful Women, Grove Press 2002

Mr. Andahazi is a popular author based in Buenos Aires who seems to have an obsession with genitals, if you judge by the two novels of his that have been translated into English, The Merciful Women and The Anatomist. (The latter won the Premio Fortabat in 1996, but the prize’s sponsor, María Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat, objected that the novel “does not contribute to exalting the highest values of the human spirit.” That may be accurate.) I don’t think all of Andahazi’s work is burlesque, but these two are what we have in English.Anyway, of the two, I thought The Merciful Women the better, more entertaining story.

In 1816, poet Percy Shelley, his fiancé, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, her half-sister, Clair Clairmont, along with Lord Byron and his doctor, John Polidori, are staying in the Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva in Switzerland. As legend goes, while stuck inside by lousy weather they had a story-writing contest, out of which Mary Shelley came up with the idea for her novel Frankenstein and Polidori started writing The Vampyre, the first modern published vampire story.

The plot and atmosphere of Andahazi’s novel seem to be based more on Ken Russell’s 1986 film Gothic than historical sources, which just makes it more entertaining (if you liked Gothic), except that Andahazi’s plot follows Polidori rather than the more famous writers.

Polidori is visited by a strange twisted creature who offers to write his story for him in exchange for, um, his male fluids. After several exchanges of liquid for story chapters, Polidori becomes obsessed with the creature and tracks it across Lake Geneva to its lair. I won’t give away the ending, but I thought it was perfect. [FGR]

Federico Andahazi The Anatomist, Anchor 1999

In The Anatomist, we have a fictional account of sixteenth-century doctor Mateo Colombo, who discovered the clitoris and linked it to sexual pleasure, naming it Amor Veneris.

[According to Encyclopedia Britannica (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Matteo-Realdo-Colombo), in his De re anatomica (1559), “On Things Anatomical,” Colombo was also the first European anatomist to correctly describe the circulation of blood and movements of the heart.]

I imagine Colombo’s find was just too juicy a story for Andahazi, and he couldn’t stop himself writing about it.

In this fanciful, tongue-in-cheek account of Colombo’s discovery, no mention is made of any woman having noticed this exciting tidbit of her own anatomy. Further, the clitoris is described by Colombo as something men could use to control women. In fact, when Colombo is put on trial for “heresy, blasphemy, witchcraft, and satanism,” part of his defense is that his discovery proves that women have no souls—as the clitoris is an organ that “performs similar functions to those of the soul in men, but whose nature is utterly different, since it depends entirely on the body.” In women, a clitoris is a substitute for a soul, and it controls all a woman thinks and feels. Who controls the clitoris, controls the woman. Colombo, however, is oblivious to how much his complementary organ is commanding his own actions.

I felt the portion of the novel taken up with the church tribunal’s charges and Mateo’s defense, while interesting, bogged down the story. The trial is as fictional as the rest of the book, which consists of Colombo’s desperate courting of a prostitute, who brusquely and continuously rejects him, and his “examinations” of other prostitutes. A short subplot follows the widow who owned the first of the clitorises Colombo “discovered” and her reaction to that discovery.

I enjoyed this odd glimpse into Renaissance politics and religious philosophy, despite the rather ridiculous plot. [FGR]

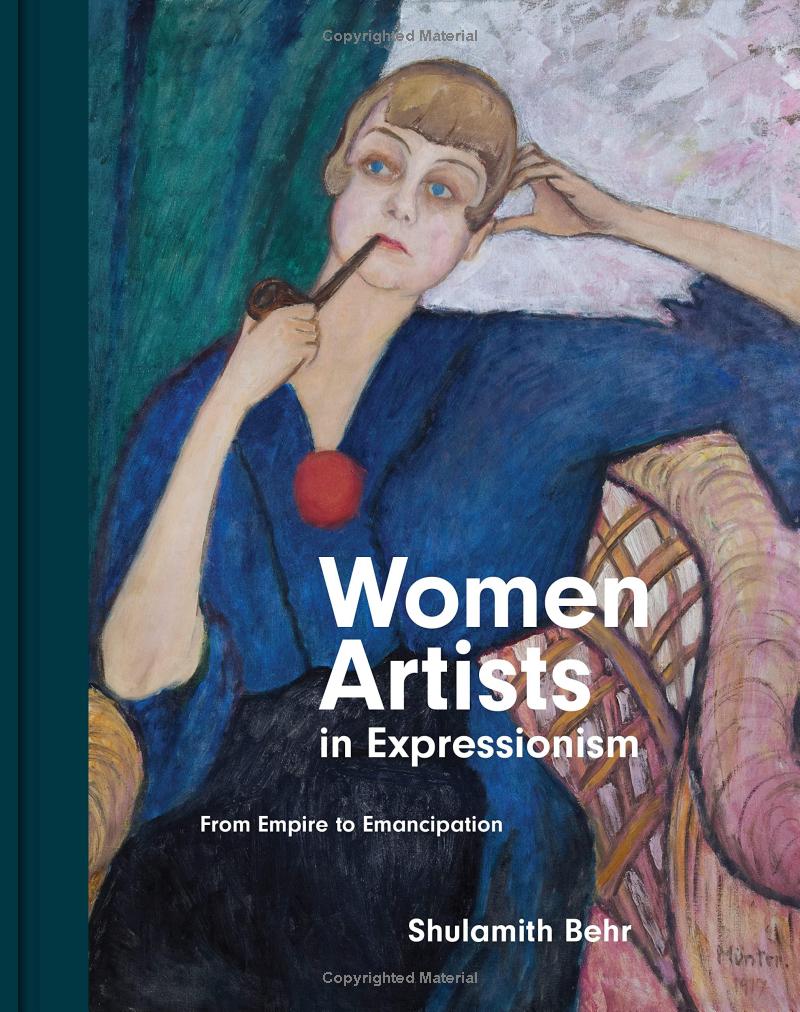

Shulamith Behr, Women Artists in Expressionism, Princeton 2022.

Sadly, Dr. Behr passed away in her London home this July. This book is a suitable close to a distinguished career. It provides an overview of the kinds of questions scholars have been asking about the first two generations of German Expressionists, with a focus on women’s part in this essential phase of Modernism. The key players, Modersohn-Becker, Kollwitz, Münter, &c. are all considered in this beautifully produced volume, with sewn signatures and extremely high quality reproductions (printed in Italy).

My best acquaintance with this field is through the works of Paula Modersohn-Becker, so I shall only discuss the treatment of her work. It has proved difficult for many to fairly assess her achievement, since one desperately does want to see through the eyes of a great woman painter, one who didn’t feel it necessary to adopt the unimpeachable style of her male contemporaries. Personally, I have some doubt whether one can really claim a first-rank woman Expressionist before Alice Neel, who is temporally and geographically beyond the range of this book.

Modersohn-Becker, who was undeniably a brilliant woman and a fine painter, died at the age of thirty-one, before she had developed her own style. She deserves infinite credit for taking her cues from the Impressionists, whom she studied first-hand during several trips to Paris—while her husband and his contemporaries at their little artist colony at Worpswede were painting sentimental landscapes—an improvement over official Wilhelmine nationalist art, but hardly adventurous. Modersohn-Becker seemed on her way to evolving an interesting style of her own, which I think one can glimpse in paintings like her 1902 “Child With a Doll Among the Birches.” But her own style, which I prize, hasn’t the primary colors and urgent primitivism of truly Expressionist painting. If we’re being honest, she’s a late minor Impressionist.

Child With a Doll Among the Birches, 1902

Modersohn-Becker owes her reputation to a carefully curated book of her journals and letters, which became a bestseller in Germany. Her friend the poet Rilke. although invited to edit it, refused to have anything to do with her repackaging as a conventionally tragic sentimental heroine. The reputation this book gained her was the greatest factor in her inclusion in Hitler’s famous exhibition of “Degenerate Art” alongside Kirchner, Klee, Marc and Nolde. With a romanticized backstory leading into her posthumous beatification as a Nazi target, Modersohn-Becker was ripe for canonization when the world wanted feminist heroines of the palette.

This unglamorous but factual account of Modersohn-Becker, rich in those grotesque ironies that hover like the maguey worms in the tequila of history, would be difficult to extract from Behr’s account, which meticulously catalogues Modersohn-Becker’s career and influences, along with every echo evoked in scholarly writing. As an academic account, the Modersohn-Becker chapter, and as far as I can tell the rest of the book, is faultless. It is a very valuable survey of the scholarship to date. But she is so careful to color inside the lines she sometimes fails to read between them. [MF]