Evan Fowler, Seeing Thing, Atmosphere Press 2023. 79 pages

Several poems from this book have already appeared in in 96, and this link will lead you to them. Needless to say, we greatly admire Fowler for his poetic skill, though it is easier to enjoy than this than to characterize it.

If one had to fit him to a niche, the best match would probably be surrealist. The narrator moves through shifting dream-like landscapes, overshadowed by elegant dread and a detached agony—

sometimes I need to scream

just toss my head back and exit through the mouth (“Entourage”)

—a mood reminiscent of the most foreboding de Chirico landscapes.

There are also fully realized narratives, like “Ennead” (a fantasy masterpiece of personified Neoplatonic numerology), and “Mermaid” (reproduced in this issue) which are Dali-like in their visually realized plausibility.

The overall mood of these poems is a feeling of unreality, expressed especially in images of drowning or weightlessness,

Once, on a long flight over sea,

I saw how dark it is up there,

how lonely it must be, sad

for shivering angels—and saw too

some clouds are just

breathlike fog! (“You Again”)

A mood which reaches perhaps its most definitive expression in the poem “A Family of a Certain Age” (previously published in 96) which begins

what should be here is not, what’s here is strange,

all the more so for seeming right. It turns a door-knob

nowhere near a door, windows are alternately

sunlit and dark, packed with blurred reflections.

The theme of loss recurs, and the one love poem, (titled “Love Poem”) though weirdly and strikingly erotic, is bracketed between evocations of death. It begins,

Of course we’ll die, in the dark

we’ll remember there was a planet once

where life pushed sweet, wet fire

through and through a glistening knot

The surreal loneliness reaches its apogee in “Age of Discovery” (reproduced in this issue)

The following excerpts from a correspondence with the author will bring him into slightly better focus,

I am certainly scarred by grief —who isn’t, at our age?— although not so badly that I frighten children and passersby. But “haunted” is a good description . . . . And being raised and coming of age on Air Force bases, particularly a few in Germany, may have something to do with my feelings of transience, this awareness I’m destined for departure. All this pops up in the book, along with my mother’s descent into dementia.

I’m an Army vet, but an Air Force brat, if it matters.

The book emerged from a full-on PTSD breakdown in 2010, during which I pretty much wrote to stay alive. And I worked hard to keep the dissociation and depersonalization in, nailing the terrors down.

The many “you’s” in the book are mostly ghosts.

. . . it’s a book of feelings, pure and simple, with minimal biographical content. I was just writing what I felt. Some poems fed on me and reflect their food, some skew memory or magically allow me to reinhabit the past, but they still have to stand on their own. I’m not interesting enough to write about, there’s enough craziness on the news.

Th. Metzger, Flaherty’s Wake, Ziggurat 2023, 402 pages. Also available direction from the publisher.

This tome, eleven years in the writing, is one of the less expected productions from Metzger’s eminent pen. It is a narrative history, a docudrama. It is written entirely in the first person voice of the main character, Charles Flaherty, Roman Catholic priest, boxer, amateur physician and abortionist, who lived in early twentieth century Rochester.

Over the years Metzger has written a number of essays and books dealing with the “Burnt Over District,” the western part of New York State which was home to so many utopian religious and social experiments in the nineteenth century: the Mormons, the Shakers, the Spiritualist Fox Sisters and the Electric Chair. Flaherty’s Wake is the magnum opus and masterpiece of Metzger’s many excurses into this weird regionalism.

Every detail related here is authentic, every event described is real. Metzger, writing in Flaherty’s literate but unpolished voice, has connected the minute particular facts into an account which is oddly credible and meticulously matches the (mostly newspaper) records. It is truer than an actual first person account could have been—for Metzger has no personal interests to protect.

This is a style of history writing that would have seemed natural to Livy or Thucydides, but which has fallen far from favor since the nineteenth century. But unlike most history written in the days of Carlyle and Michelet, Metzger’s is scrupulously unbiased. Here you will gain a true view of the beliefs, ethnicities, and social circumstances of early twentieth century Rochester and environs. It could not be bettered by the most impeccably dull academic account. And one does not have to pay the dues of boredom which is the usual price of such fine detail. This is a compelling, page-turning read.

It is, however, a little bleak. It made me think of Scorsese’s film The Irishman, which is similarly a docudrama, but focused on an associate of Jimmy Hoffa. There, as in Metzger’s book, the narrative was weirdly compelling albeit grim throughout. The chronicles of men whose lives are full of somewhat illegal action tend to have a gloomy glamor.

In the life of Flaherty the abortionist priest, you will not find a hero of feminism or of faith. The only real faith he seems to have had was faith in himself.

Metzger has created here a valuable work of history, which raises more questions than it answers, but which one thanks him for asking.

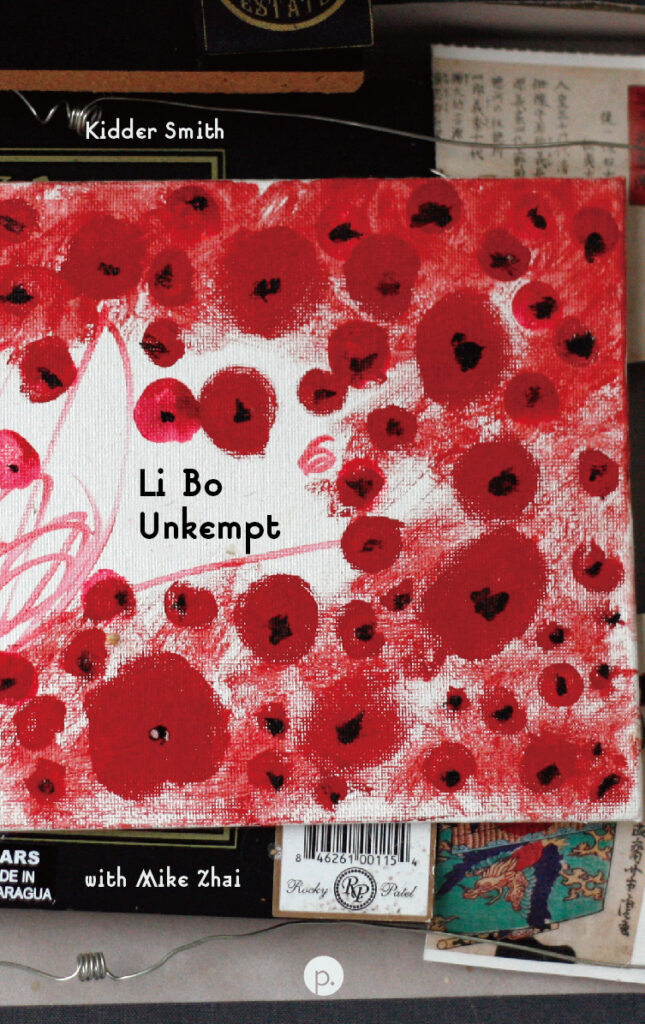

Kidder Smith, Li Bo Unkempt, Punctum Books 2021

Though published a few years ago, in 2021, I can find no review of this book online. Since it is a work of rogue scholarship, neither dully academic nor shallow and popular, it is meant for that rarest of markets—people who neither have to read it (for their thesis) nor want to read it (because there’s nothing good on Netflix they haven’t seen.) This is a book for people who need to read it, because they’re looking for something rare and strange, something that might transform their existence.

It creates, from an ever shifting perspective, a kind of holograph portrait of the Chinese poet Li Bo, contemporary of Du Fu, who like him lived through the collapse of the Tang dynasty.

Li Bo is generally regarded as one of China’s greatest poets, on a par with Du Fu. Yet the experience of reading him in translation is oddly unsatisfying. Arthur Waley, the twentieth century’s most gifted translator from Chinese to English, didn’t think Li Bo deserved his reputation. The surviving thousand poems attributed to Li are in fact rather flat. But they have been included in all the great Chinese poetry anthologies since his own time (the 8th century), and at this point they are “classics,” with whatever that implies.

Personally, I think the beauty of Li Bo was lost with the pronunciation. Since Chinese is non-syllabic, there is no secure record of just what it sounded like. Think of how much English has changed since Chaucer, when the “k” and the “gh” in “knight” were still audible. And Chinese, being pictographic, doesn’t have syllabic tracks to reconstruct the sound with.

Whether we consider (with Waley) Li Bo as bit of a fraud, or consider him, as I do, a victim of the Chinese writing system, he had a tremendous reputation in his own day, and indisputably great poets like Du Fu honored him. There is no reason to doubt his achievement.

He was also, by every account, a charismatic, fascinating character, whose claims to Daoist magical attainment and daring swordsmanship were, true or not, enthralling to listen to. He was a great drinker, a free spirit, a wild and charming eccentric. He makes me think of the Beat poet Gregory Corso, who was similarly brilliant, self-destructive, startling and hilarious.

Kidder Smith has restored to us Li Bo as he must have appeared to those who knew him. Smith gives generous and accurate translations of the poems (Chinese text legibly included), makes racy digressions into the background history: the weak corrupt emperor, the femme fatale favorite who toppled the dynasty, the barbarian general who led the insurrection and burned the capital. These alternate with excurses into Daoist mythology and alchemy, fetchingly phrased and psychedelic in effect. Throughout we veer from scholarly citation to pop-culture quotation. Smith uses every means, fair or unfair, to bring Li Bo to life.

Trying to review this book is like attempting to describe Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. It’s a vast overcrowded vista of occult-poetical detail, which can be enjoyed as much for the sheer language as for the content. No sober translation so much as touches the hem of this re-creation. And Punctum books makes it available for free pdf perusal or download, so you needn’t take my word for it before you pony up the modest sum for a hard copy of this magnificent (and richly illustrated) book.