Prologue

I will tell you the secret of human happiness . . .

Once upon a time there was a king who had one son, and he wanted to hand over the kingdom to his son, not as an inheritance but as an outright gift, while he, the king, still lived. To celebrate this transfer, the king held a great feast. Now, whenever a king gives a feast, you may be sure it’s a very joyful event—even more so when it’s made on the occasion of the king giving, while he still lives, the whole kingdom to his son.

So the celebration on this day was exceptionally glad. All the nobles were there, the princes and the dukes, and everyone, of whatever rank, had a delightful time. In fact, the entire country rejoiced that the king was giving the realm to his son, for the king’s recognition of his son’s worthiness redounded to the king’s own glory.

It was quite a party, nothing lacked that could have perfected the festivity. There were musicians and acrobats and clowns, everything that could intensify the general pleasure.

When all the joy was at its height, the king stood up and said to his son,

“Because I am also an astrologer, I can read in the stars that the day will come when you will lose this kingdom. Whether you forget it, or forfeit it by some sad act—it really doesn’t matter. The day will come when you will find yourself fallen from this royal state. When this happens, take care you don’t succumb to sorrow. Even though you’ve lost this kingdom, remember this one thing: strive to be happy in spite of all. If you can manage to be happy, I will be too. But even if you succumb to sorrow I’ll still be glad, because this kingdom is well rid of a such prince, for how could someone take care of a whole country who can’t even look after his own happiness? What sort of a prince deserves to be happy if he can only be so when he has no problems at all?

“But if you do manage somehow to recapture happiness in spite of everything, then I will be preternaturally happy.”

The king’s son energetically assumed his royal responsibilities. He created nobles to administer the kingdom, dukes and lords directly responsible to him, who would implement his plans exactly.

The king’s son became a great intellectual, a philosopher, a scientist, a lover of everything reason can do. He gathered around himself the foremost thinkers. If any remarkable specialist or profound expert came to the kingdom, he could be sure of recognition and reward. Persons of scientific distinction were given riches, honors, whatever they wanted.

Since science was held here in such extraordinary esteem, the whole country dedicated itself to research. That was clearly the career of choice for anyone with talent. Due to this exceptional emphasis on knowledge for its own sake, the military arts were forgotten. Such practical matters took a less than second place in the rush for knowledge. Before long, the stupidest person in the country would have been considered a sage anywhere else. And as for the wise men of that country—these were wild, promethean geniuses! But all this wisdom led its possessors into skepticism. Since they now knew nearly everything, they believed in almost nothing. This same fate befell the king’s son. He became a materialist and an atheist. The malaise didn’t extend to the common people. They remained unscathed because such vast disbelief required a depth of insight which was quite beyond them.

Now the king’s son was a good man. He was born good, his character was good, and he couldn’t help wondering, “What is my place in this wide world? What am I supposed to be doing?” He was sure he had known it once, and he struggled now, with deep groans and sighs, to remember.

He kept wondering, “Why on earth am I pursuing these lofty studies that leave me with more questions than I started with? What does it all mean?” But no sooner had his common sense awoken in this manner, it was crushed by his critical faculty; his skepticism was too strong. And thus he went on questioning his own questioning of his questioning until all he could do was groan.

It came to pass in a certain country that everyone had to flee. They made their escape through a forest, and there they lost two children, a boy and a girl, a son from one family and a daughter from another. They were very little children, only four or five years old. The children had no food with them, and when they got hungry they screamed and cried.

Meanwhile a beggar approached them, a beggar with a sack on his back. The children hugged and clung to his legs. He gave them bread; they ate, and he asked them where they came from.

They answered, “We don’t know!”—and how could they? After all, they were very young children. When he was about to leave, they begged him to take them with him. He said, “You can’t follow where I must go.” While he spoke, the children looked up at him, hoping to see the chance of a better answer, and they noticed he was blind. That was a surprise. If he was blind, how did he know where to go? And indeed, it’s no less of a surprise that that the children wondered about this: they were hardly more than toddlers. But since they were exceptionally bright youngsters, it did strike them as remarkable.

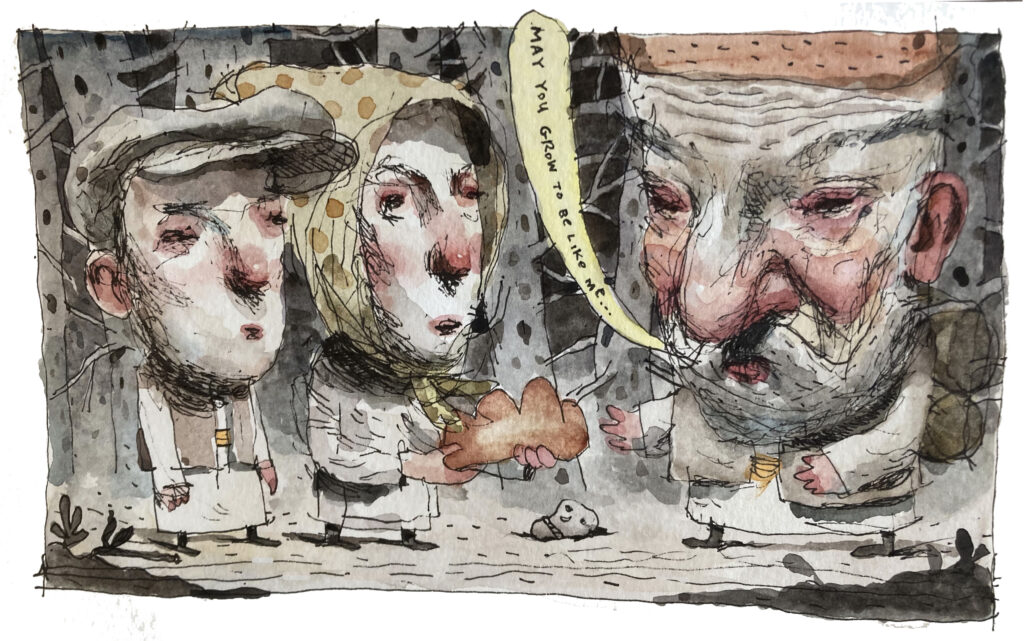

He blessed them, the blind beggar did. “May you grow up to be like me!” He gave them more bread, then went away. The children understood that the Holy One, the God of Israel, was watching over them and had sent the blind beggar to feed them.

But later, when the bread was all gone, they started screaming again, “We’re hungry!” Night fell, and they slept right there, with the forest floor for a bed. Early in the morning they woke up and realized they still had nothing to eat, and began again to weep and wail—when another beggar arrived, a deaf one. The children began talking to him, both at once, but he raised his hands and motioned to them to stop. He said, “I can’t hear at all.” This beggar also gave them bread to eat. When he began to walk away the children wanted him to take them with him, but he wouldn’t have it. He did however bless them, saying, “May you grow up to be like me.” He gave them more bread, and left.

When they ate up that bread they started to wail again, and another beggar came, this one with a terrible stammer. When the children tried to speak to him, all his replies were broken and tongue-bumbled. They couldn’t make out a word, though he understood them perfectly well. He too gave them bread, and as he left he blessed them too, saying “May you grow up to be like me.”

The next beggar had a crooked neck, but otherwise this encounter worked out the same as the previous two. Then came a hunchbacked beggar, a beggar with no hands, then one with no feet, and every one of them gave the children bread and blessed them, saying, “May you grow up to be like me.”

By the next time they ran out of bread they had come to a settled region. The forest path became a road which led them into a village. There they were received into a house where people took pity on them and gave them bread. They knocked on the door of another house, and there too they were given bread. And so they went from house to house. This was working out quite well, they never wanted for food. The children decided they would always stay together. They got themselves sacks to hold the bread they collected. They went to all the celebrations, circumcisions, weddings and bar mitzvahs, where the take was even better. The went to a city and there they begged at fine houses and in the marketplace. They took their place with the professional beggars at the city gates and held out a bowl for coins. Eventually they became well known in beggardom—everyone had heard of the two children who were lost in the forest.

One day there was a great fair in a big city. All the beggars went to it, the two children as well. It occurred to the other beggars, wouldn’t it be a fine thing if the two children were to marry one another? The discussion ended in a pleased and speedy agreement: so the children became engaged. But how could they celebrate the wedding?

Now on such-and-such a day the king would be celebrating his anniversary. They could all go there and beg fine white bread and roasted meat, and that would take care of the wedding banquet. They went, they begged, and collected all the royal leftovers. Now they needed a hall in which to celebrate the wedding. They hadn’t the money to hire one, or the skills and materials to build one, so what they did was dig a deep wide pit. Like the grave, it was big enough to fit everyone. To make a roof, they covered it over with fallen tree-trunks and branches, then reeds, then they shoveled dirt and dung-heaps on top of all that. You would never guess it was there. It was a buried palace.

They went in to hold the children’s wedding, set up the wedding canopy. Everyone was very happy, none more so than the bride and groom, who remembered all the loving kindness shown them by the Holy One, the God of Israel, when they were lost in the forest. They began to weep with longing to see once more the first beggar, the blind one, who had fed them in the wilderness.

“If only that blind beggar were with us today!”