Aelita, Queen of Mars

Aelita, Queen of Mars (1924) was based on a 1923 novella by Aleksey N. Tolstoy, a distant cousin of War and Peace author Leo Tolstoy. It is set against the background of the then just concluded Russian Civil War, and tells the Walter Mitty-like tale of a rocket scientist whose fantasy life (on Mars) parallels his marital troubles and the revolutionary situation.

It’s not always an easy film to follow: there are several well-developed major characters (as one would expect from a Russian novel), and the transitions between fantasy and reality are not clearly marked. What makes this somewhat boring film worth seeing are the sequences set on Mars, which are masterpieces of Constructivist costume and set design.

In the early twentieth century Russia embraced, simultaneously, fifty years of art history which Europe went through in successive phases. Impressionism, Symbolism, Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism and Futurism, all coexisted in Moscow and St. Petersburg. When truly abstract art arrived in the teens of the twentieth century, Russia was already up to speed, and painters like Malevich and Kandinsky were in the forefront.

Constructivism was the application of geometric abstraction to the design of functional objects, from bridges to teacups. One could view it as the Russian version of the Bauhaus. What was most unique in Russia was short-lived embrace of this avant-garde style by the government, as the official revolutionary aesthetic, before Stalin outlawed it and replaced it with the kitsch of Soviet Realism.

Aelita was a propaganda film, and the architecture and costumes in the Martian sequences are Constructivism in motion. In the YouTube film,

one may wish to see these first, and perhaps these only: they are from 4:25-9:15, 17:55-18:37, 31:18-38:14, and from 60:00 to the end of the film.

Alexandra Exter, who designed the costumes, was a mostly Cubist painter, whose work is quite respectable, though not really remarkable. The costumes in Aelita are not really on the same level as the Oskar Schlemmer’s for the Bauhaus Triadic Ballet. Nor are the sets, by Isaac Rabinovich and Victor Simov on a par with the engineering feats of Vladimir Shukov. But unlike their high-art betters, the experience of Aelita is unabashedly easy and fun.

And contextually, Aelita is not without significance. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the Flash Gordon serial from the 30’s, and even Barbarella owe more than a little to Aelita. What Salome (1924) was for Art Nouveau, and The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari was to Expressionism, Aelita is to Constructivism.

But wait, there’s more.

Interplanetary Revolution

Originally designed as part of Aelita, but released on its own (since Aelita is confusing enough without it,) Interplanetary Revolution (1924)

is one of the strangest pieces of early animation you will ever see. It would be best to view the seven-plus minutes before reading my explication, since it’s even more wondrous if you don’t understand it.

The cartoon opens with the smiling face of Comrade Cominternov, who wears a budenovka hat, a pointy, soft woolen hat which was standard gear for Russian Communist soldiers from 1917 to 1922. The cartoon rendering of this headpiece makes it look a bit like the German Spiked Helmet (Pickelhaub), which may cause some confusion for first time viewers, but the Red Army star makes it clear that this is the hat of the good guys.

We are then introduced to the Capitalist powers, in top hats with white ties. These have features associated with the powers that opposed the Revolution and supported the Whites. The English (Bulldog), Germans (Swastika, a German nationalist symbol for some time before its adoption by the Nazis), the Americans (the stars on the top hat suggest Uncle Sam), and the French (who eat frogs). These international capitalist greed-monsters drink the blood of the worker.

But the truth of Marx, as expressed in Pravda, is hair-raising even for these death’s heads. The red star, which now appears even in their mirrors, shows them to themselves in their bare-naked ugliness, to the amusement of Cominternov.

The failure of Capitalism is announced globally via telegraph, to the consternation of Russia’s enemies, particularly the axis powers Turkey (fez with crescent) and Germany (Iron Cross). The long arm of Communism reaches out for the Capitalists in their homes, and they hide ineffectually under their beds. In the darkness of their bedrooms they are quite literally haunted by the specter of Communism.

The Capitalists, sporting the symbols of wealth (top hats) religion (cross) nationalism (swastika) and militarism (medal, uniform) flee into outer space (literally) to save their fat asses that are now under fire. Their space-ship is shaped like a shoe because they are using it to run away.

A Soviet space ship is sent in pursuit, with a good Communist pilot. (It’s not Stalin: such moustaches were pretty standard of working class men of the time.) We see in silhouette Cominternov (recognizable by his budonovka hat,) puzzling over a map. (The pilot is not holding a gun, that’s his hand, index finger extended to point out the right route.) Cominternov is now oriented among the stars and planets, which fit into his hat (his understanding encompasses the cosmos.)

Pursued now by the Soviet ship, the capitalists first encounter Venus, the planet of love, with painted lips and goo-goo eyes, from which emerge a pair of lovers. The woman’s breasts extend with arousal (a shocking sight for the decent Cominternov) and the lovers’ shared breath forms a heart from which new-borns emerge.

The capitalists fly into the mouth of Venus, and love-intoxication makes them lose their money. (Capitalism leads to prostitution.)

They pass Mercury, who is of course the god of thieves and merchants. Next comes the sun, whose many hands indicate his powerful rays, and he blows the space travelers away from his dangerous heat.

Cominternov and his navigator discuss the best route to take while Mars appears ever closer through their ship’s window.

We first see Mars in the person of two robot-like figures who represent the planet’s energy and industry. There is considerable airship traffic. The planet itself, like the sets of Aelita, made in Constructivist style. The pilot and Cominternov fight the space-centurions who police it. Electric bolts fly to indicate ray-gun activity. Cominternov rallies the workers, there is a space-ship battle between capitalist and revolutionary forces. The success of the workers is telegraphed back to earth, where Lenin (who had died a few months previous to the film’s release) flickers into view as the information arrives, to show that his dream of global revolution has been realized on a cosmic scale.

Seducing the Ferryman, Whimsical Tales of Sex! and Death!

Burlesques by Forsythia Groundhogg-Robin, Faust’s Bargain Books 2019.

The collector’s drive for completeness is an understandable, if demanding, obsession. Little boys collect stamps, little girls acquire herds of toy horses. Generally speaking, such pursuits are abandoned at puberty, and one seeks the grander satisfactions of accumulating money or grudges.

Yet there are always a few determined persons who retain the faith that happiness may be captured in a microcosm. Encyclopedists and museum curators are respected representatives of this species—of which sexologists form a memorable genus.

A genus with two main families. Those who, like De Sade, are exhaustive within the spectrum of what they unabashedly enjoy, and those who, like Havelock Ellis, take a seeming interest in everything, to misdirect attention and gain themselves liberty to discuss at, unblamed length, what they really like.

To which category does the present volume belong? A difficult call. The perspective is so broad that, had a thematic index been provided, it might have been articulated as animal, vegetable and mineral. Sex with vampires, statues, flowers, all the way up (or down) to sex with Vladimir Putin, all figure in this unabashed mènagerie.

This is not, however, a “one-hand read” or “breathless prose.” The author is a true encyclopédiste, eighteenth-century style, like Diderot or the dear old Marquis. What makes it worth reading, and has earned its author a place in the pantheon of our regular contributors, is the understated humor and poetical style that disarm disbelief and create an experience of the extraordinary. Like her forebear Ovid, Ms. Groundhogg knows that we’re still ready to believe in mythology if we aren’t first told we must take it seriously. Here, as at the opera, you leave your common sense with your hat and coat on entering and enjoy a rich aesthetic experience on its own terms.

Another interesting feature of the book, which may not be immediately apparent, is the author’s utterly pagan point of view. Magic and metamorphoses are present everywhere, without excuse or explanation, as a steady feature of the physics of existence. Death and gore are as omnipresent as the sex, and the most primal topics are handled with the easy glee of Greasy Grimy Gopher Guts. It is as though the aforementioned Ovid, the amoral Roman master of erotic verse, had been reincarnated in the North Jersey of the Sopranos. One of the Ferryman tales, Chasing Golden Autumn, which appears in this issue, is a good example of the erotic nature mysticism, carried to an almost mukbang level of sensory overload, delivered with poetic power, that sets this strange volume apart.

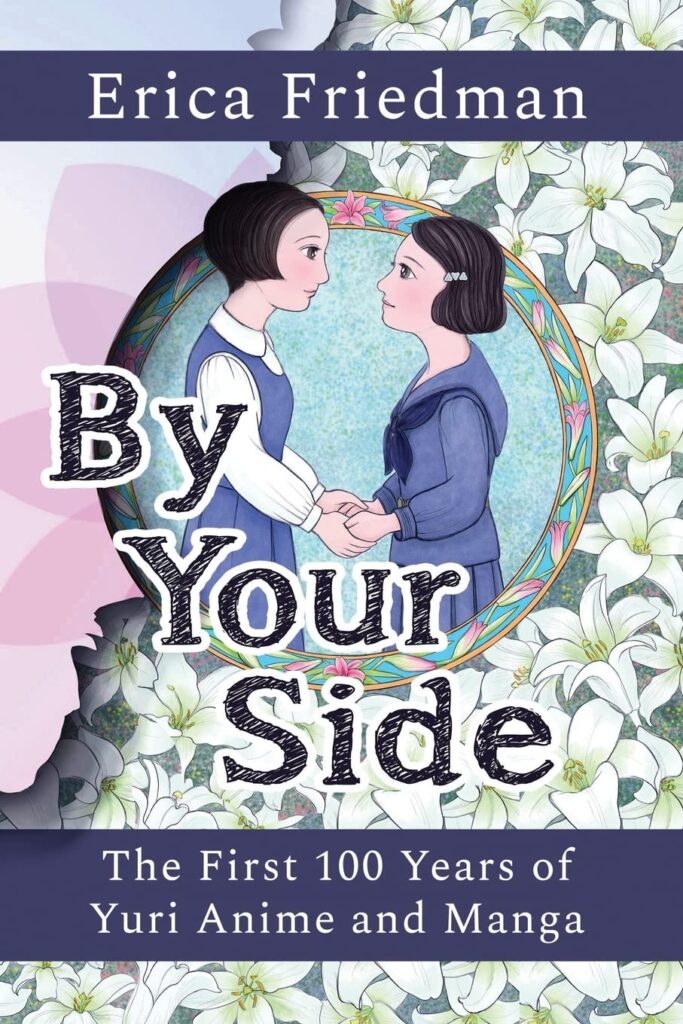

By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and Manga Erica Friedman, Journey Press, 2022.

This is a magisterial treatment of lesbian anime and manga; a groundbreaking work that provides the first mapping in English of a little known and fascinating subcultural world. The book contains articles and essays Ms. Friedman has written over the last twenty years, during which she has made an international name for herself as an expert in the field—and has been interviewed in 96. The particulars of her website and credentials may be found here.

The writings are a kaleidoscope of topics and insights which the reader is invited to browse through at random or as led by whim and interest. This was well advised. Despite this modest presentation, the thematically grouped studies offer an encyclopedic tour of the now century-old phenomenon of lesbian-themed cartoon narrative. In every section one finds detailed, precise, insightful and accurate information. It is the indispensable point of departure for any further research in this field.

It is a reference work: Ms. Friedman’s training in library science has served her well. The book has all the virtues of such a work. But as such, it may not be the best choice for the general reader. Reference works presuppose a certain level of familiarity with the subject.

Who may consult this with pleasure and profit? Those who are already dealt into the game, either as fans of the genre, or as academic researchers in Japanese popular culture. Outsiders who wish to appreciate the depth of Friedman’s work will want to read this in front of their computer, Googling the references. This is particularly at issue as regards pictures. The greatest obstacle to enjoying this book is the small number of illustrations. One understands that a small press has not the means to secure permission to use all the contemporary art cited here, but it can make the text opaque to someone not already very familiar with the material.

One comes away from a consultation of this book wishing that Ms. Friedman would write another, less profound and more chatty one. The tone in By Your Side is serious and professional, describing the evolution of Yuri themes from the earliest Well of Loneliness type lurid allusion to twisted tastes, through such well-loved cliches as religious all-girl boarding schools or all-girl motorcycle gangs, to alternative families where lesbianism is accepted and valued. Friedman relates this evolution as a chronicle of political liberation and successful Feminism, a perspective which is accurate, and claims respect for the subject.

But Friedman’s knowledge could also, I think, produce a widely appealing, timely, and fun book. Now, when one thinks for writing a book to sell, one immediately pictures something squalid, along the lines of “Hot Lesbians of Wacky Japan.”

A presentation more antithetical to Friedman’s could not be imagined. The problem is not that lesbians aren’t erotic beings, or that Japan isn’t an exotic place, it’s that presenting these facets of the topic as merely matter for monetization is in effect a kind of psychic tourism.

Tourism is about appropriating and degrading the Other (as dear old Simone de Beauvoir used to say). The full criminality of tourism can fully be appreciated when we compare it with pilgrimage, which is a manner of visiting that adds to the sacrality of the place visited. The pilgrim makes the journey, while the tourist takes a vacation, takes pictures. Language itself makes my point.

A book in which Ms. Friedman went into more detail about her own evolution of identity, her own pilgrimage, for which Sailor Moon provided a validating catalyst, would be a tale worth hearing. And a fuller treatment of Yuri anime and manga in the context of Japanese culture, as a specialized lens through which to view it, would make for a rich experience. Let me take up just one of the countless glittering bits of insight that are mentioned, but not developed, in this little encyclopedia. Osamu Tezuka, was in a sense the Japanese Walt Disney, the father of Japanimation. His work is best known to us in the cartoon of the space-age Pinocchio, Astro Boy.

This androgynous android, with huge and seemingly mascara’d anime eyes, and shellac’d flapper’s bob, is a symbol of Japan’s self-reinvention in the wake of World War Two. How this came about, and succeeded to the point where and the western world, at a certain age, finds the realm of Pikachu irresistible, is part of the story of Yuri, and one which would find many interested readers. Ms. Friedman has the particular expertise and the breadth of culture to accomplish this, and she does not lack the strong opinions necessary to shape the material.

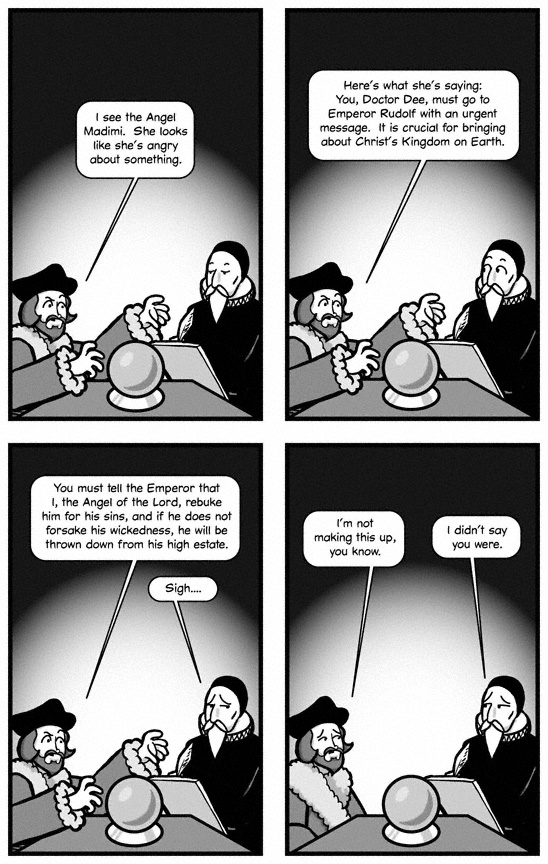

Me & Doctor Dee, A Jape, comic book, Drowned Town Press 2012

In what the publisher correctly describes as “thirty-six pages of occult Renaissance high jinks,” E. J. Barnes relates the partnership of John Dee and Edward Kelley, the former a gullible astrologer, the latter a charismatic rogue. Seeking their fortune, and sometimes their safety between Elizabeth I’s England and the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, they commune with angels, transmute base metals into gold, and experiment with free love.

It might be better described as a play than a comic book. The figures are fairly static from frame to frame, but the dialogue is very funny indeed, and the changing facial expressions support it well. As the bibliography given at the end would suggest, all the events are meticulously researched and accurately related. The speeches however are done in casual modern vernacular, enlivened here and there by an archaic phrase. The effect however is not shallow or smirky, but genuinely entertaining. One thinks of the Monty Python sketches and films where the influence of Terry Jones is particularly evident, as in Holy Grail or Life of Brian. Jones studied literature and medieval history at Oxford, and his renditions of Arthurian chivalry and the politics of ancient Palestine go to the heart of the matter in a way that delights the knowledgeable. So it is with Barnes’ Doctor Dee. It’s a wonderful piece of historical comedy. I wish someone would film it on their smartphone and post it on YouTube as a series of sketches. With real actors and a good director, this would be a wonderful addition to the canon of Elizabethan comedy.

Barbara A. Holland, After Hours in Bohemia, The Poet’s Press, 2020. Free download at Archive.Org, and at the Poet’s Press

In the 1970’s and 80’s, the poetry-reading scene in Manhattan was divided into the St. Mark’s Church Poetry Project, run by Naropa apparatchiks and the open readings, which were dominated by out-patients. The only qualifications to perform at either venue were a loud voice and a shameless mind. The open readings were however haunted (I used the term advisedly) by two remarkable talents, the brilliant Brett Rutherford, whose stories are a regular feature of 96, and Barabara Holland, whose poems make their 96 debut in this issue.

Holland was a tall gaunt sibyllic crone who recited her mantic masterpieces from memory, standing straight, fingers fanned, eyes fixed on infinity. In the last few years Rutherford, Holland’s oldest and most loyal friend, has published her work through his own Poet’s Press—one of the longest-lived and most distinguished small presses in America.

After Hours in Bohemia is the uncollected poetry: the work that appeared in small magazines and never made it into a book, or never got past the notebook and manuscript stage. Rutherford has done a magnificent job collecting and editing these, sometimes adding a polish or other completion to the manuscript work. This is entirely appropriate: Rutherford knew her for decades, as a friend and fellow performer and as her publisher, so he is well placed to fathom her intention. And also, Rutherford is a first rate poet, one of the finest now writing in English, so even if he has taken some liberty, he knows well what he is doing and we are the richer for it. Indeed, having acquired Holland’s poetical works in the new Poet’s Press edition, I picked up this volume first because I wanted to see what a Rutherford-Holland synthesis was like.

Holland was, by twentieth century standards, a disciplined and classical poet. Her most remarkable achievement is her poetry in the style of Magritte. Magritte himself, so far as the pure rendering went, was merely an accomplished academic painter. It was his ideas that were wonderful, though some of these, like the man with the apple in front of his face, have been reproduced to the point where our eyes are numb to the startle.

Holland has admirably managed truly Magritte effects in her poems, of which those excerpted in this issue give a fair sample. And even her language in these poems has the clarity and restraint of Magritte.