Right around 2000, I became frustrated with the artificial division between text and image in Western art and I experimented with combining them. Emerging out of my sketchbooks were characters and historical interests that I worked up into a series of large posters. Honestly, I had no idea where they’d end up when I started, but a few landed in independent weeklies around North Carolina, and the rest were exhibited in galleries, local gathering places and, to my delight, were used by various organizations. Working with text actually gave me more imaginative freedom, as the images were no longer burdened with the responsibility of telling the entire story.

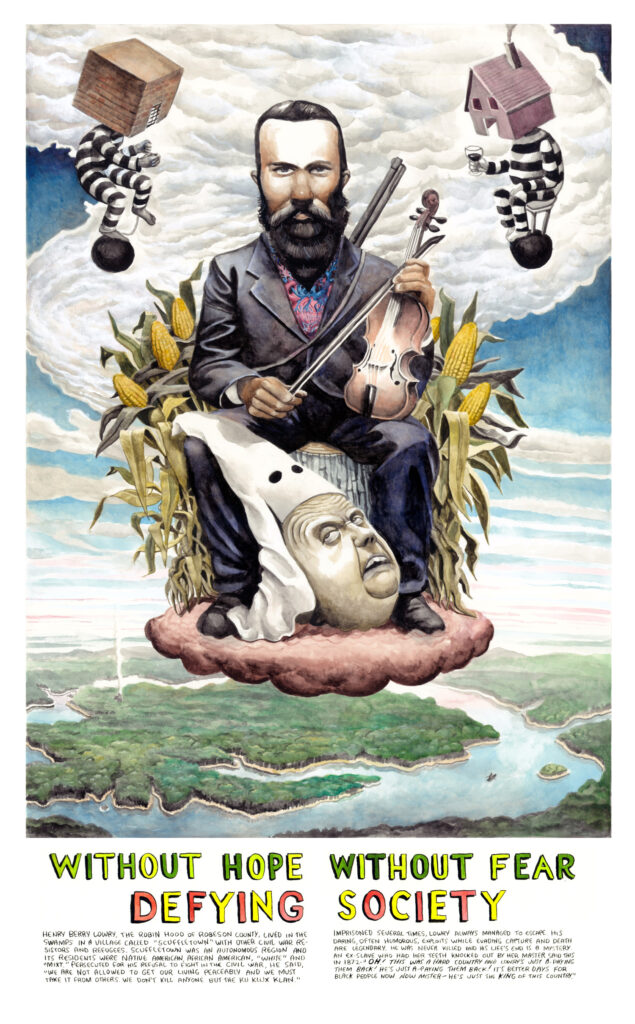

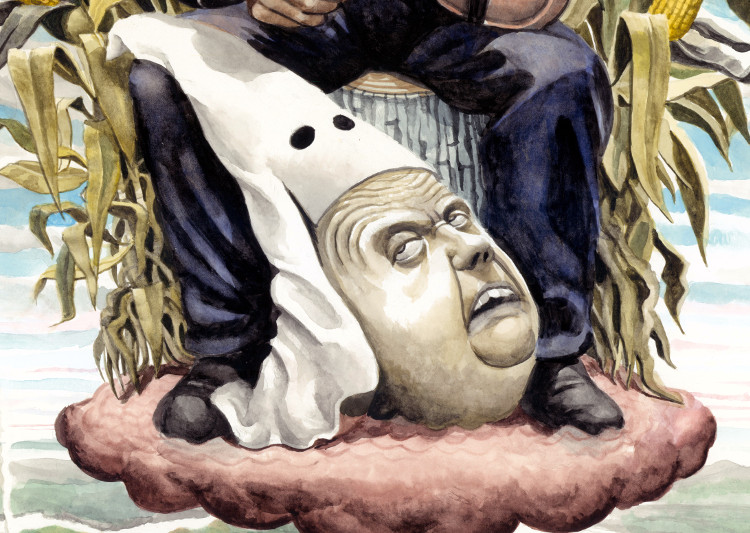

In Primitive Rebels, Eric Hobsbawm wrote that the Robin Hood phenomenon wasn’t limited to one figure but was part of a historical wave of such figures around the world. One of them was surely Henry Berry Lowry. Active in North Carolina (around Wilmington) during the post-reconstruction reaction, Lowry led a band of merry multi-racial/ethnic rebels from his base in the local swamps, where the local militia couldn’t reach him. He did it all—broke out of jail multiple times, stole from the rich, gave to the poor, and even insisted once on playing a fiddle tune before a rare negotiation with the town’s white ruling class. He was once the most wanted man in America but he was never killed and never found.

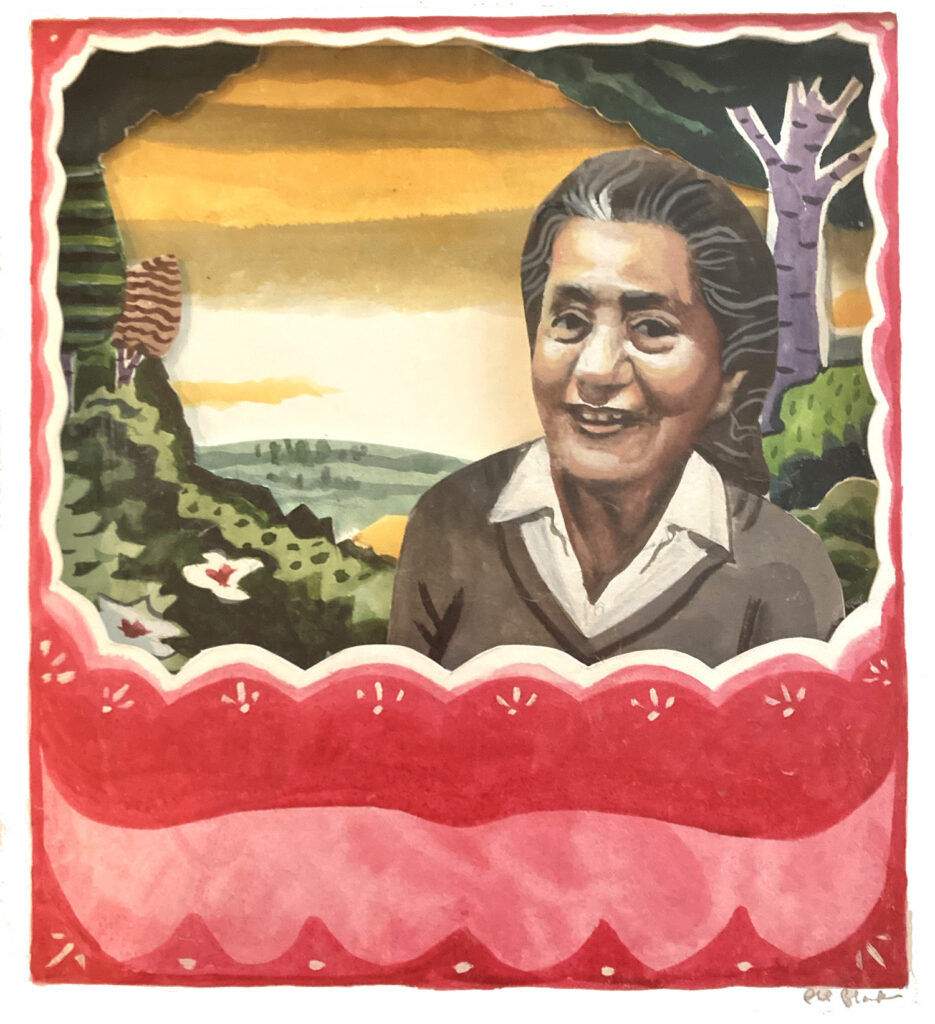

Vera Lachmann was a believer. As a German Jew, she always insisted on a life of art, music, poetry and good company. In 1939, she escaped the Nazis and landed in rural North Carolina. Against all odds, she established a magical little camp in the mountains full of both avant-garde and classically informed music and art. The centerpiece of the camp were midsummer performances of classical plays. In addition, over the eight weeks of camp she told (not read, told) the story of The Iliad and The Odyssey by the campfire. I did this painting as part of a story about her that ran in the Asheville weekly, The MountainXpress.

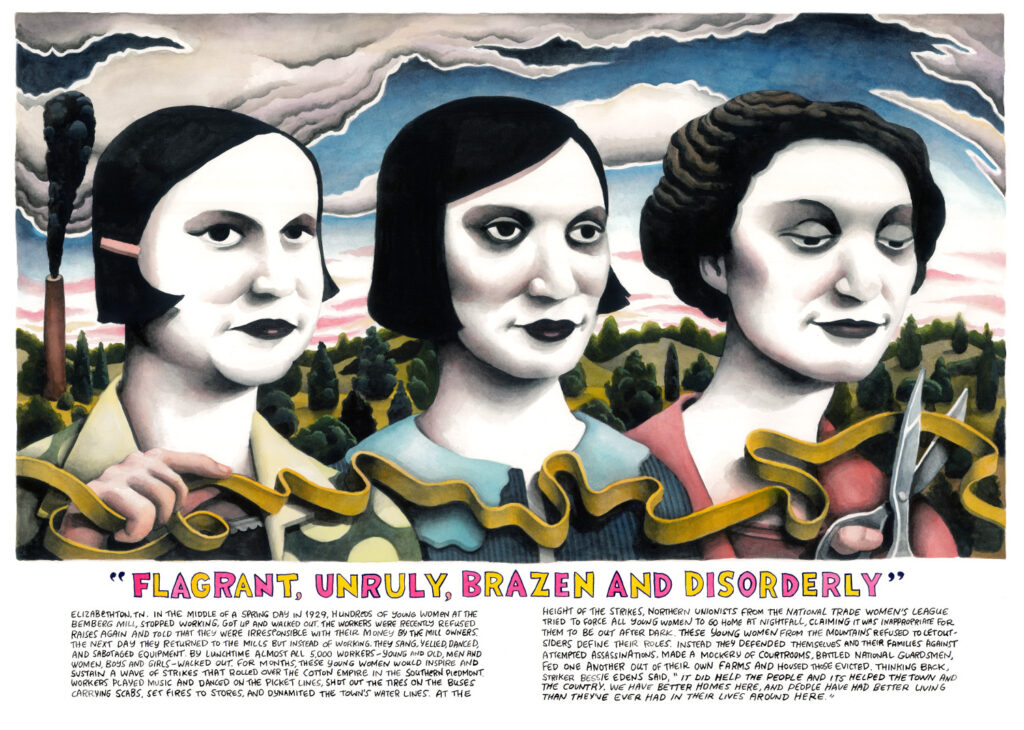

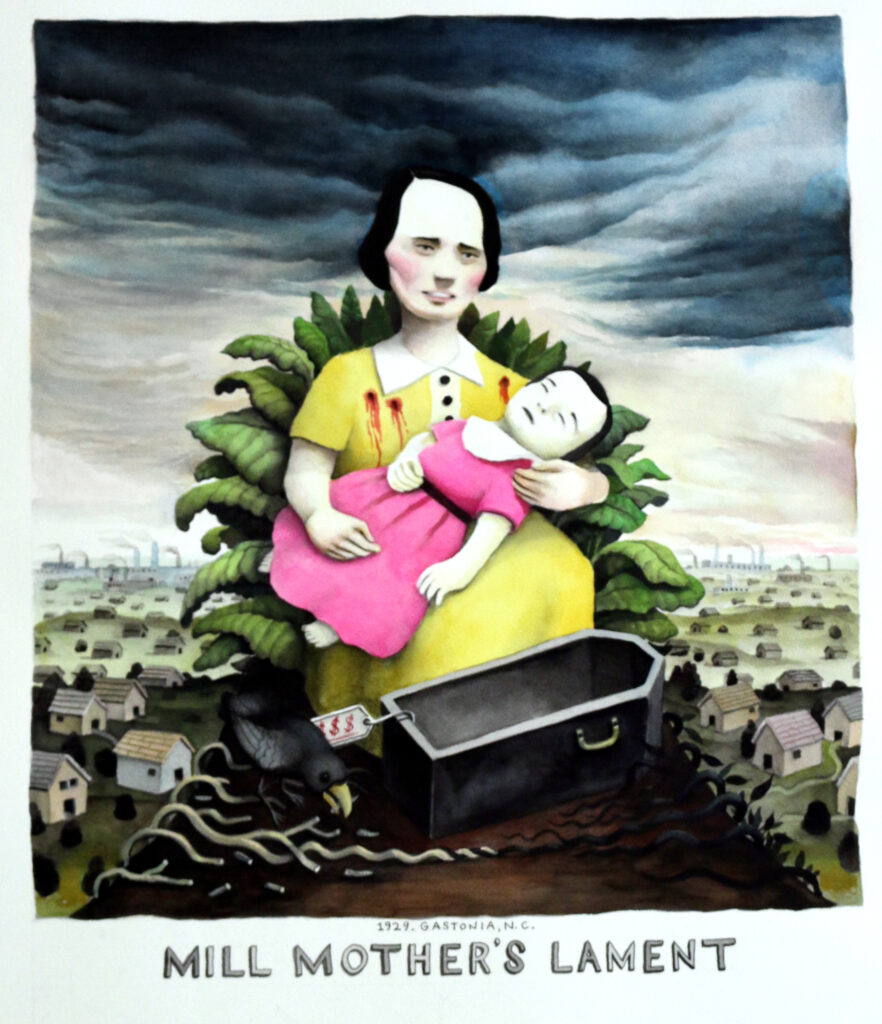

Around 2013 or so, I started a series of paintings in partnership with the authors of Dixie Be Damned: 300 Years of Insurrection in the American South. This painting was a testament to the women who worked in the textile mills around Charlotte and Gastonia. The story centers around a huge strike and is long and complicated. As opposed to other stories which had identifiable heroes, I wanted to paint pictures of people who could stand in for the hundreds of anonymous workers who participated, and came up with this trio of Fates.

The textile strikes also produced another figure, the worker, musician and martyr, Ella May Wiggins. The writers of Dixie Be Damned mention her briefly but I wanted to tell her story more fully. She was, in many ways, a labor hero similar to Joe Hill. She wrote songs, she fought for the union and she crossed color lines during one the heights of Jim Crow segregation. Like Joe, she was killed by the ruling class for her transgressions. Here’s the painting before I added the text. Read more.

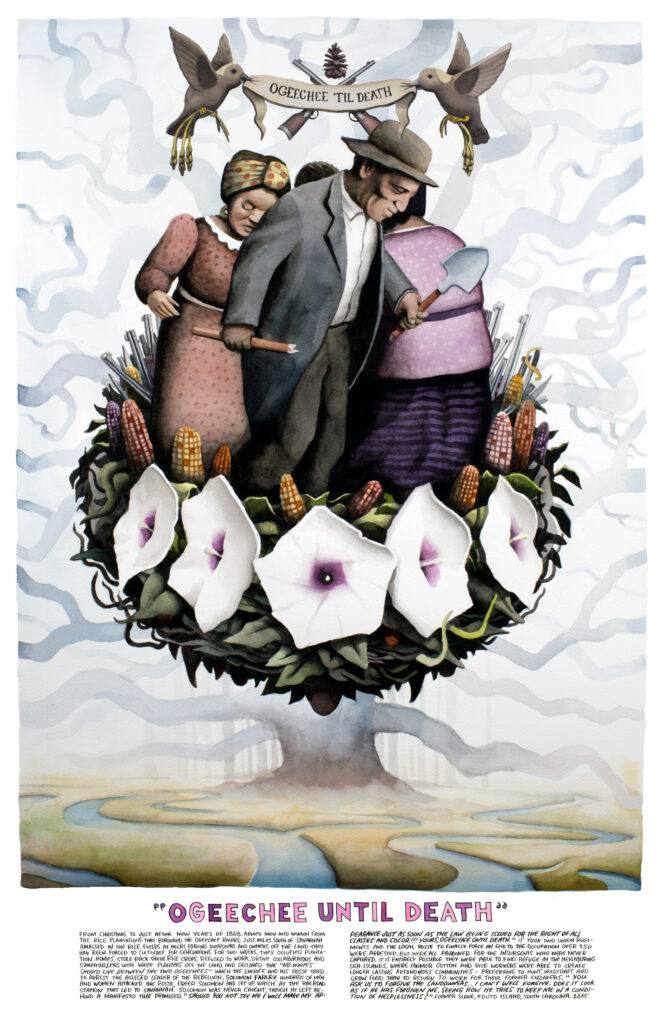

The next two images were also made for the Dixie Be Damned series. Ogeechee Until Death tells the fascinating story of what happened to the rice plantations, and the former workers and owners of them, in the wake of the Civil War. The story involves a problem—what happens to cash crop plantations when no one is forced to work on them? The answer, at least here, was that, even when the almighty Gospel of Profit was preached, the ex-workers were happy to just grow their own subsistence crops and did their best to be left alone. Without Southern slavers forcing them to work through violence, the federal government had to step in and basically fulfill the same role. This image again required me to paint a collective of people as opposed to specific people.

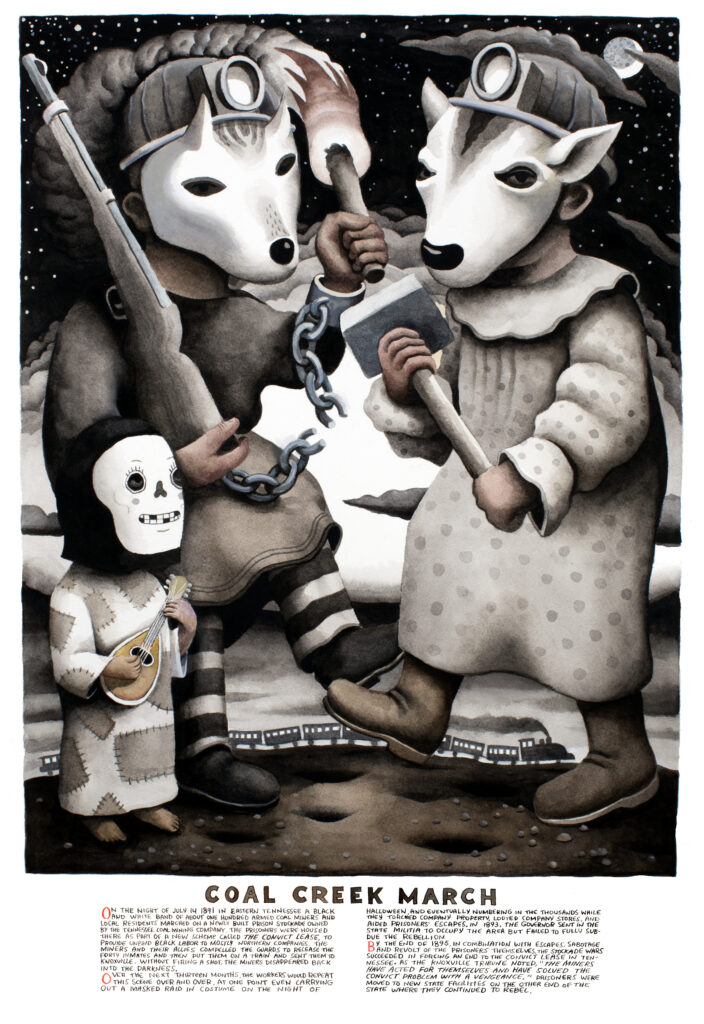

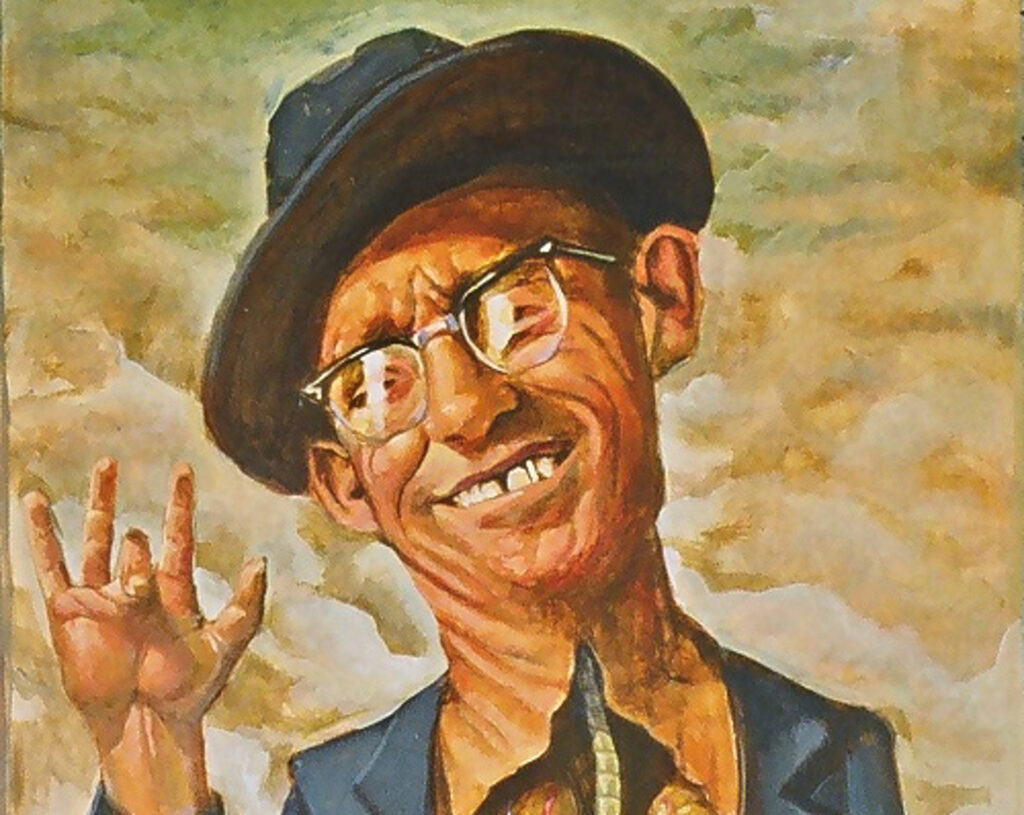

Coal Creek March brings us to Tennessee at the end of the 19th century. This is a story that takes place well before the better-known Harlan County strikes but is equally fascinating. The climax occurs on Halloween night, 1891. Under the pretext of celebrating at a country dance, some of the miners, disguised in Halloween attire, slipped out and launched an attack on the local mine.

This area’s history, especially as regards the solidarity between the white and African American miners who worked in this region, is largely forgotten. I also had to do quite a bit of research on what halloween costumes looked like in the 1890s—turns out they were properly creepy. The mandolin player is an homage to “Louie Bluie” aka Howard Armstrong, an African American polylinguist, musician and artist who recorded originally as part of the amazing Tennessee Chocolate Drops.

North Carolina is a “vale of humility between two pillars of conceit.” Meaning that because its neighbors, South Carolina and Virginia, had better ports, they developed a strong moneyed elite class and culture that North Carolina never quite had to the same extent. North Carolina’s coast was less suited to big ships and became, for example, a harbor for pirates. It also required skilled and capable sailors, which in the 19th century, mostly meant transatlantic Black sailors. This has always had a subtle but persistent effect on the culture of North Carolina and may be one of the reasons the holiday Jonkonnu, mostly celebrated in the Caribbean, was also found here and nowhere else in the American South. Jonkonnu features rough music and congenial begging (think Halloween and Mardi Gras) during Yuletide, the week between Christmas and the New Year. The holiday itself has gone through transformations and appropriations, similar to other mummer traditions, that have turned its already topsy turvy meanings upside down and inside out over the years. When I did this painting there was very little published about it in North America. I’m pleased to see there is now much more information available.

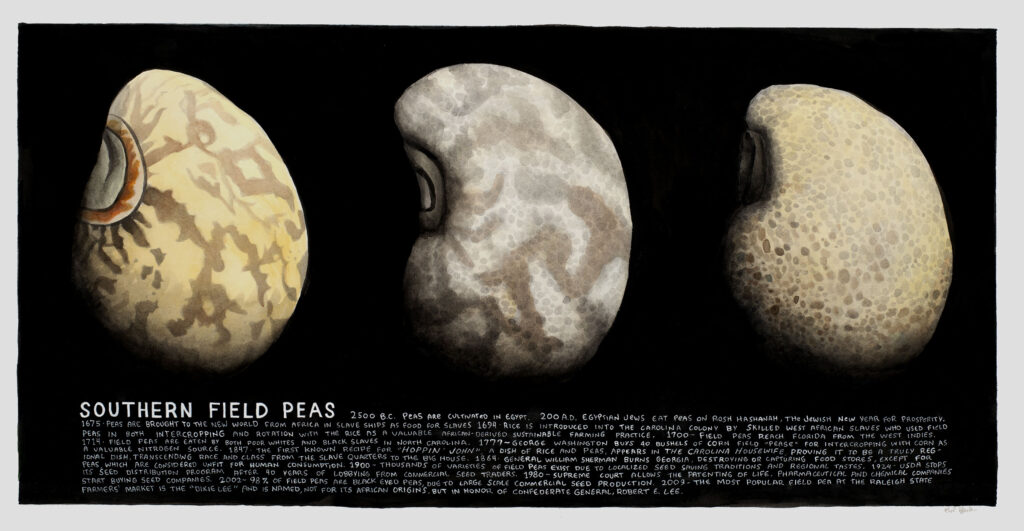

I’ve probably done more paintings of Southern Field Peas than just about anything else. In the South, it is the custom to eat these on New Years’ Day, a tradition that extends back to ancient Egypt and was part of the Saturnalia traditions of Rome (but don’t tell Pythagoras, the notorious legume-o-phobe). This particular image was part of a bunch of paintings that tried to highlight the history and diversity of vegetables in Southern cuisine, as an antidote to the endless clichéd images of BBQ.

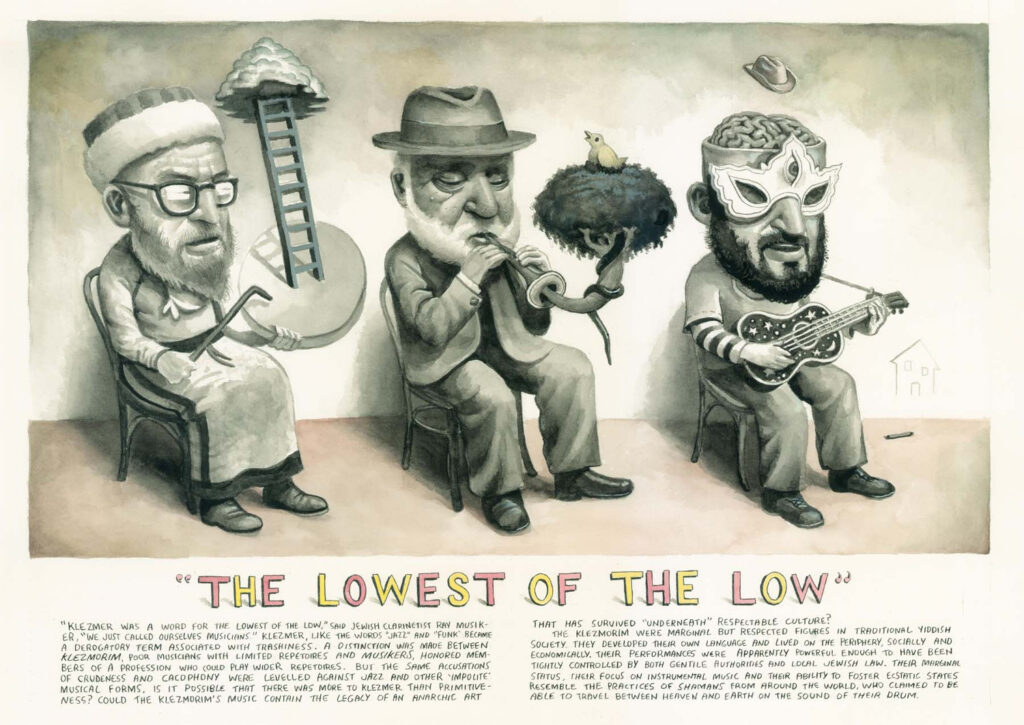

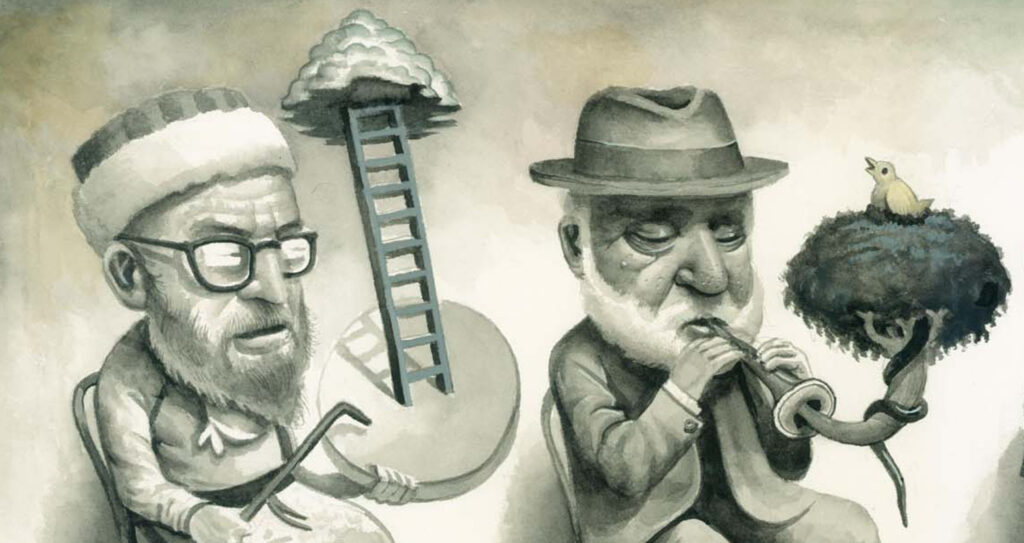

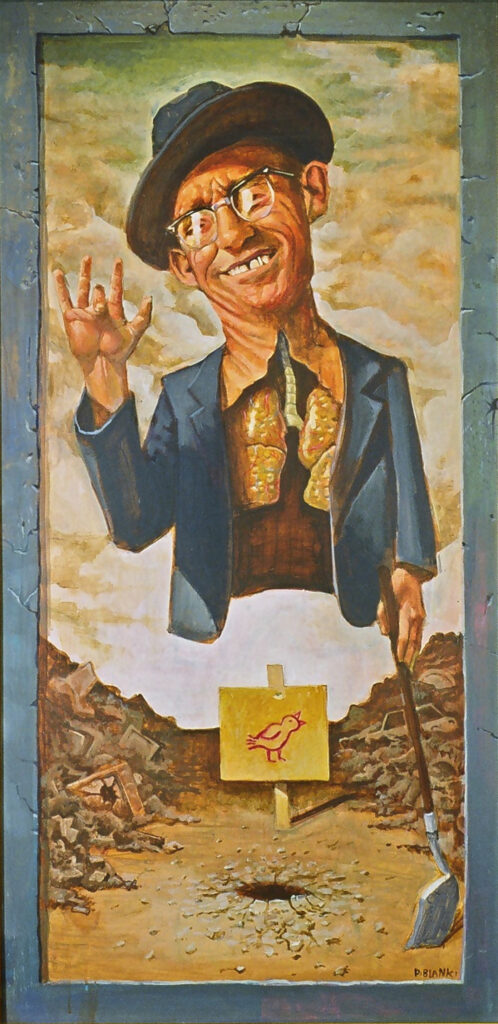

A Tickle in the Heart is a great documentary about The Epstein Brothers, one of the last of the pre-revival klezmer acts. In it, one of the brothers scoffs at the word “klezmer” (Jewish instrumental folk musician, more or less), which he said referred to the “The lowest of the low.” In the klezmer scene, this sentiment is usually conveniently ignored or apologetically ceded. But I wanted to take a look at it from a different angle. Maybe the klezmers never quite got to tell their side of the story.

By the 20th century, they were (possibly, probably?) the holders of a quickly vanishing ecstatic trace whose presence had represented a threat to the normative power structure for hundreds of years, much in the way similar “folk” musicians have functioned in the South and indeed, worldwide. It’s complicated and I ended up devoting a good chunk of my life to studying this music and culture and even ended up writing a book on it that no one will ever read. Oy!

Why do they say “a land of milk and honey”? Is it significant that they are both pastoral foods (as opposed to the crops grown by sedentary folks in the land of slavery)? Is it significant that they are key ingredients in a primitive alcoholic beverage? Is the honey referred to bee-honey or sugar from figs? I never did find out! But In my research on Judaism and its repressed musical traditions, I came upon the female drumming prophets, including Deborah (“Bee”) and the ancient Bee-cult which extended throughout the female Mediterranean. This image was discovered and used by the delightful College of the Melissae, who do a great job of researching and maintaining this fascinating culture today.

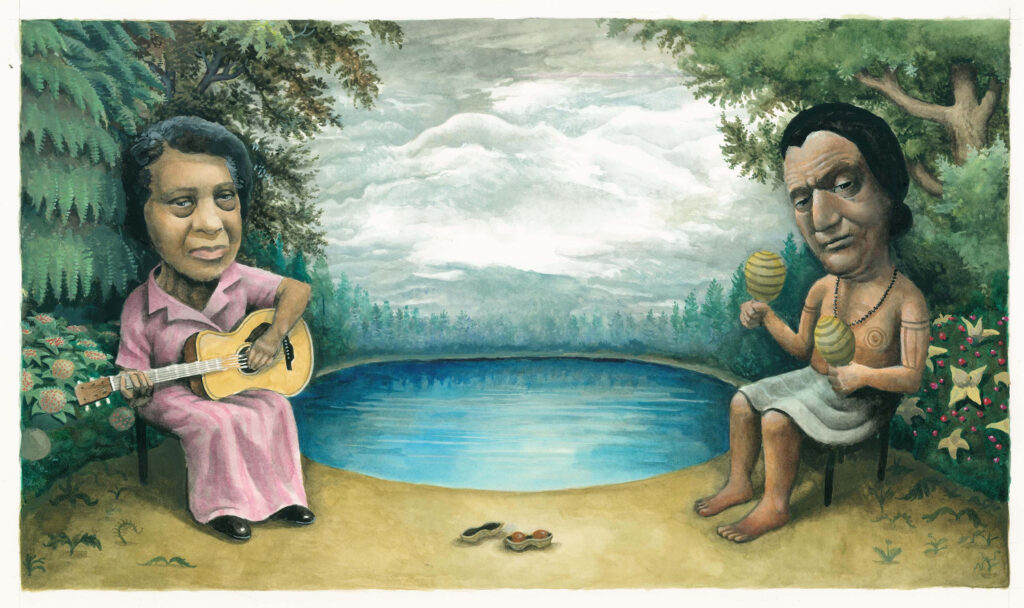

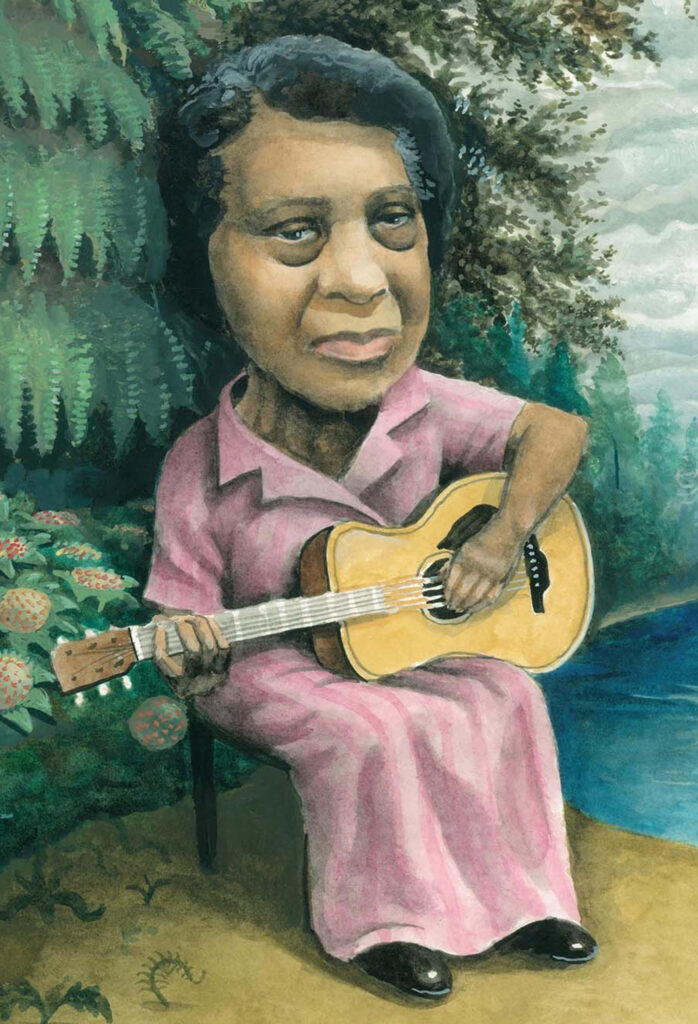

Here’s one I wish I could do over, as I was still emerging from my “big head” phase and the exaggerated heads don’t do justice to the seriousness of the subject. In some ways, it’s the most important image to me of all. Elizabeth Cotten lived in Carrboro, NC before she moved up north and was “discovered” while working as folk musician and scholar Mike Seeger’s housekeeper. Ms. Cotten was a deceptively brilliant guitarist and songwriter who, due to her gentle style of playing and unobtrusive personality, had a tendency to be sentimentalized by her admirers.

In studying Central North Carolina’s indigenous and musical history, her song “Shake Sugaree” became entwined with several other histories, including an amazing account of a musical performance in 1701 by Enoe-Will for the sleepy English explorer, John Lawson. It’s a long story but you can read it here: The peanut shell refers to her lyric: “I got a little secret, I ain’t going to tell, I’m going to heaven, in a brown pea shell.”

This is an example of an earlier phase of painting that happened right before the watercolors. This is a large acrylic painting of Roscoe Holcomb, a powerful musician from the middle of the 20th century. I’ve always been drawn to his strange contradictions- he sang and played banjo in a painfully intense manner but was known as a warm, gentle man.

His music was considered archaic, and was, but he was younger than, for example, Bill Monroe, who was already negotiating an escape from the culture of the pre-modern South. He seemed to float right above the crossroads of the industrial and the pre-industrial, somewhere between the heights of spiritual beauty and depths of material pain.

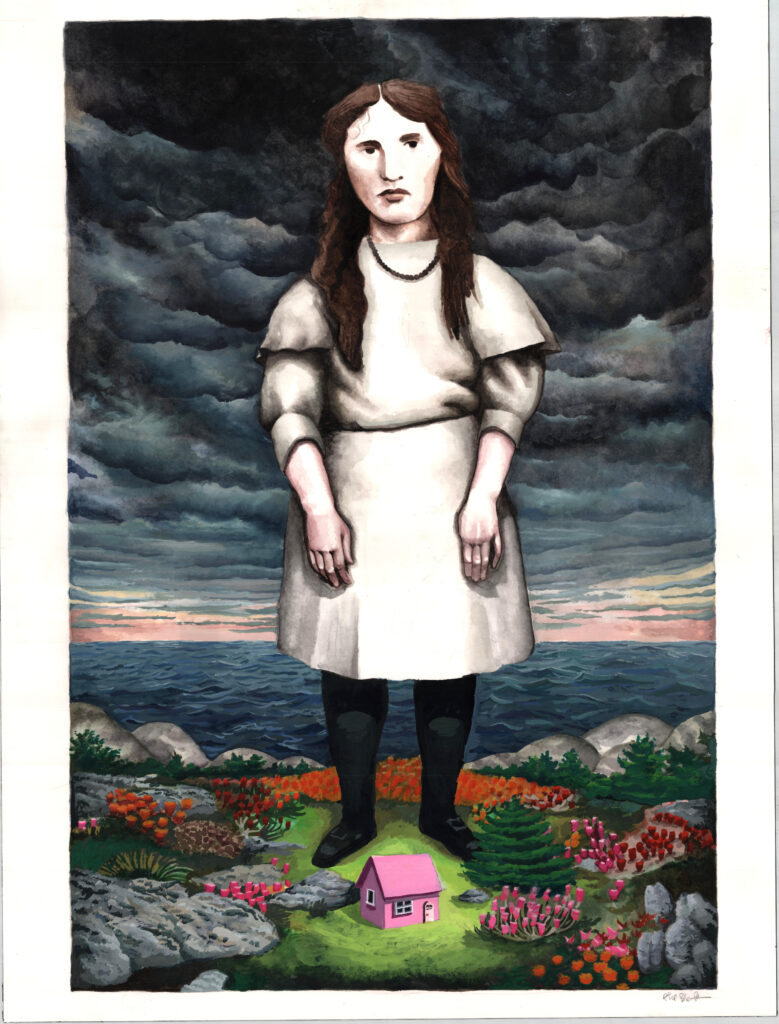

This is my wife’s favorite painting and it still hangs over her dresser. It’s an image of Sara Carter of the musical Carter Family fame, wearing a dress she made herself and dreaming of homes in the midst of heavy storms out on the oceans deep. Maybelle Carter was the guitar genius and steady heartbeat of the trio, but my wife April helped me hear that Sara’s high harmonies were the soul and animating genius of the band.

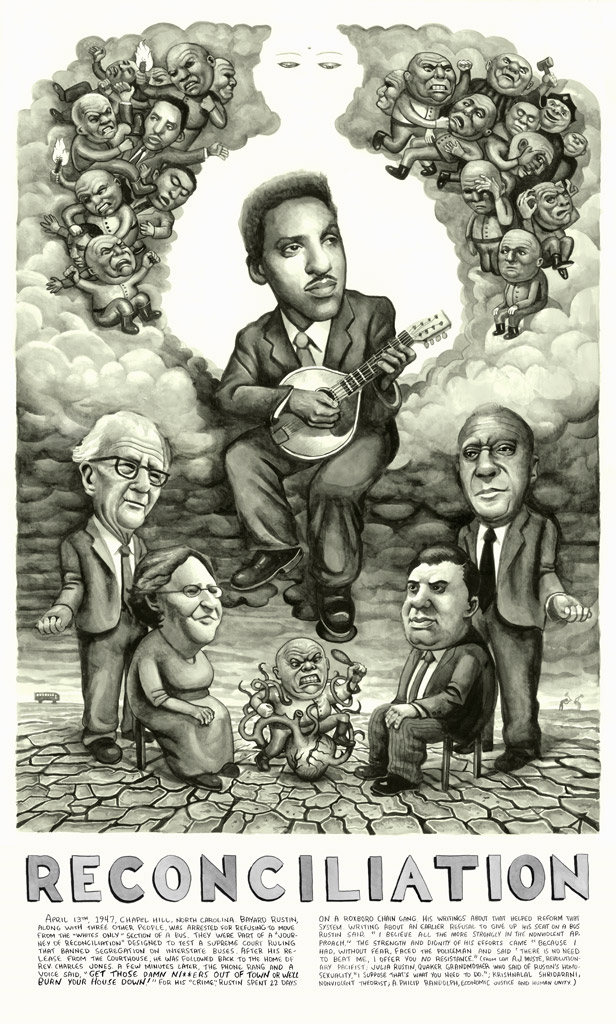

Bayard Rustin was an activist central to the history of Civil Rights in the 20th century. The importance of his influence was intentionally repressed due to this homosexuality. Among his many contributions, he was instrumental in translating the ideas of nonviolence from Krishnalal Shridharani (pictured) to the Civil Rights movement. In the background is a bus and a chain gang, referring to his time in Chapel Hill where he was arrested and put on hard labor as part of an effort to desegregate interstate busing. Turning his adversity around, he wrote about his experiences and contributed mightily to reforming the brutalities of legalized penal slavery. In the figures above Rustin, I tried to portray the journey from aggression and ignorance through shame and rage and into profound awareness.