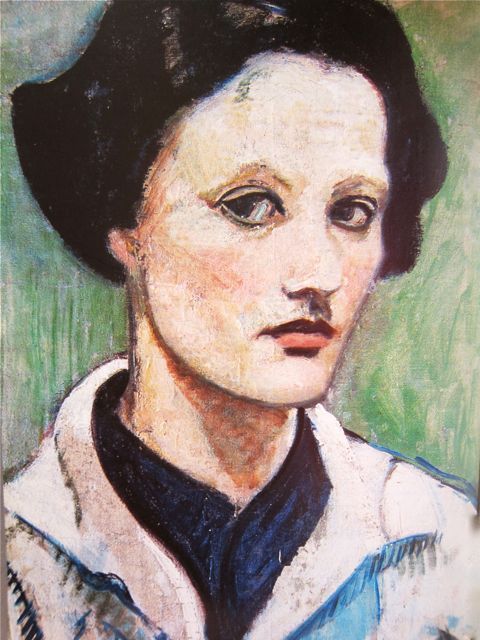

self-portrait c. 1925, Eva Zeisel Archive

Her Life

The playful, fluid, abstractly organic shapes of her iconic white pottery are featured in the design collections of MOMA and the Victoria and Albert Museum. She spent sixteen months in a Soviet prison accused of attempting to assassinate Stalin. She evolved new ceramic designs that were put into production from America to Japan, without a break, until her death at the age of 105. For those who can name the great industrial designers, Eva Zeisel, along with Ray Eames, is probably the only woman whose name comes readily to mind. Her sculptural ceramic work made use of distinctively feminine shapes as Georgia O’Keefe did in painting. Reckoned by her achievements, scope of career, and celebration of the female forms, Eva Zeisel is a heroine of feminism.

Eva Striker Zeisel (November 13, 1906 – December 30, 2011) was born inBudapest, Hungary, when it was still a twin capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Hers was a wealthy, highly educated, assimilated Jewish family. Her mother, Laura Polányi Striker, a historian, feminist and political activist, was the first woman to get a PhD from the University of Budapest. Her father, Alexander Striker, was a successful textile manufacturer, the first to produce Rayon in Hungary.

Zeisel’s early education was in “advanced” schools where the children ran around naked and learned to dance and paint. Later, she was more formally educated by private tutors, and went on to study painting for three semesters at the Hungarian Royal Academy of Fine Arts, but then put painting aside and apprenticed herself to a master potter, becoming the first woman to be enrolled in the guild. A year later, at age 18, she set up her own studio in a garden shed behind her parent’s house. She affected then a draw-string blouse and leather sandals, and produced folk-art style pottery which she sold at a local market.

This was a time when a back-to-nature life style, and disapproval of industrialization, were very much a part of avant-garde and youth culture. Throughout her career, Zeisel would remain faithful to the folk-art simplicity of her first work. Her latest creations, though highly streamlined and abstracted, were still visibly inspired by animal forms and naively ergonomic shapes of folk pottery. She was always at odds with hard-edge doctrinaire modernism, which she characterized as “soulless,” “high-falutin’” and “dictatorial.”

But she soon put behind her any dogmatic adherence to folk art ideas, and went work in German ceramics factories, first as a hand craftsperson but rapidly rising to the rank of designer. Her work from this period is extremely competent, in the Art Deco Style.

She would not discover her own idiom until after her return from Russia , where she went in 1932. She expected that “the worker’s paradise” would provide limitless artistic freedom in the company of ceramic designers whose work was truly new. This had not even been entirely the case in the first years after 1917. In the experimental early days of the revolution, when Modernism had freest play in graphic design, especially in posters, abstract pattern decoration was ceramics was allowed, but it was still applied to the traditional shapes.

In 1932, when Zeisel arrived, Socialist Realism was abruptly declared the only legitimate artistic style. Before she had any chance of conflict by ceramic innovations, she was caught up in the whirlpool of denunciations that spread virally with the onset of the Stalinist terror.

Zeisel’s Soviet Prison Photograph, 1936, Eva Zeisel Archive

On May 28, 1936, she was arrested on suspicion of plotting to assassinate Stalin. This was the beginning of the Purges, in which millions were executed on trumped up charges as Stalin eliminated anyone he thought might oppose his consolidation of power. Zeisel was held and interrogated for sixteen months, ten of them in solitary confinement, until September 1937 when she was abruptly released and deported to Vienna, thanks to personal interventions that remain a bit murky, but may have involved a lover who rose to rank in the secret police.

She returned, terribly traumatized, and was promptly married by Hans Zeisel, a distinguished sociologist one year her senior, who had been in love with her since 1931. As she put it, “I simply did anything I was told, almost like a robot. . . . Hans took over.”

Eva and Hans emigrated to America just in advance of the Nazi takeover, and then began a hardscrabble existence. Zeisel was sculpting a plaster Himalayas for a film set for fifty cents an hour, when she heard of a job opening at the Pratt Institute, which led to her founding of its ceramics department.

1946 Castleton Museum service: vegetable dish, creamer without handle, Eva Zeisel Archive

From there she found various employments designing for pottery companies, and built a reputation, which crested in 1946 when she was given the first MOMA exhibition to feature a single woman designer. It also was the first such to be devoted solely to pottery. Her creation, the Museum dinner service for Castleton China, was the first modern dinnerware line in fine white china produced in the postwar United States. This austerely beautiful set proved a commercial failure—the 20% failure rate firing the delicate, subtly undulant pieces made it too expensive to produce. But these critically lauded dishes launched her career as a serious designer. Zeisel herself said that this set marked the transition between her “compass and ruler era” and her “lyrical” style with its “poetry of the communicative line.”

It would be unhelpful to list her projects and successes from this point in chronological order. As a freelance designer for the better part of a century, she worked for some thirty different manufacturers world-wide, whose concerns ranged from the purely commercial or practical to high-end and high-concept. To narrate every episode would obscure the overall trends and give too little attention to her masterpiece achievements. Thus I will survey only the work which best represents her unique and sculptural vision.

Triumph of the Heimish

In 1947 Zeisel followed the critical success of the Museum line with a popular one, the Town and Country set of inexpensive “luncheon ware” produced by Red Wing Potteries in Minnesota, in an informal style appealing to younger, post-war consumers, and which was intended to feel “as Greenwich Village-y as possible.”[4] Unlike the museum line, this was solid, durable, and brightly colored, in playful bulbous shapes. Among these were the iconic salt and pepper shakers, which may have inspired the “schmoo” character which appeared in Al Capp’s Li’l Abner comics a year later.

The Town and Country “schmoo” salt-and-pepper shakers., author’s collection.

Judaism was not an important part of Zeisel’s conscious identity—in 1940 she joined the Unitarian Church, to facilitate her integration into American society. But the emotional warmth of the forms she created, many of which naturally nestle together, like the salt and pepper shakers of the Town and Country dinner set, are very Jewish in the way they exalt human relationships. Zeisel said,

“I have rarely designed objects that were meant to stand alone. My designs have family relationships. They are either mother and child, siblings, or cousins.”

The kitchen, more than any other room in the house, has historically been the center of the Jewish home and warm, relaxed Jewish hospitality. Zeisel’s friendly ceramic shapes, which beckon and invite with their relaxed curves, expresses a very Jewish sense of the heimish —a Yiddish word which means “informal, cozy and welcoming.” There are many designers contemporary with Zeisel who used similarly softened streamlined shapes, but none which so convey the sense that not only the guests, but the very tableware, is part of the family.

This sense of inclusion was literally “baked” into Zeisel’s pottery. The sense of play in Zeisel’s shapes has often been remarked, but there is more to this than fun. The seeming mobility of her work, the way her forms seem to be unrehearsed and still happening, is part of what draws us in. An appreciation of lucky, accidental and momentary grace, the potential candor of form, was a deliberate principle for Zeisel, who said,

“Spontaneity is, of course, a most engaging aspect of communication. It gives us a feeling of immediacy and participation in the act of creating the work. By contrast, one may feel excluded when looking at something precisely formed and well finished.”

The Body Ceramic

Zeisel’s postwar work is part of a movement in design called Biomorphic Modernism. This tempered geometric Bauhaus austerity with organic, irregular, wavy curves. Such fluid organic shapes were already prominent in the surrealist art of Hans Arp and Joan Miro, and the architecture and objects of the Finnish designer Alvar Aalto; they entered the world of industrial design in Russel Wright’s pottery and the furniture of Breuer and Saarinen. In America, they often characterized the far-ranging design work of Charles and Ray Eames.

Zeisel was part of this major movement in art and design, but within this she had a special gift for continuous forms:. This is particularly visible in her spouts and handles, which flow seamlessly into the body of the object, and which made them seem like living things rather than constructed objects. To this she added a uniquely feminine quality, a mood of nourishing undulant abundance which is visible even in the most slender and elegant of her shapes, which always manage to have curves and never seem meager.

Describing her work, Zeisel liked to use womanly and maternal terms. The rounded curves of her 1950 Norleans China porcelain dinnerware, which was cream-colored and nearly flesh-toned she likened to “a baby’s bottom.” The wood and ceramic dining accessories she designed in 1951 for Salisbury artisans, with very rounded bowls and cruets and similarly curvy but thin and upwardly stretched candlesticks, she describes a “bulging” and “waistline.” The Tomorrow’s Classic dinnerware she designed for Hallcraft in 1952, she called “a happy family of shapes.”

The Feminine Divine

Teapot, 1952 Hallcraft China Tomorrow’s Classic series. Photo: author’s collection.

In the Tomorrow’s Classic dinnerware, designed specifically for daily use, she perfectly balanced her distinctive style with practicality. The elegant curvaceous shapes express an inner generosity: they are visually satisfying. The teapot from this series is a splendid example of her plenteousness—infinitely appropriate for tableware. These rounded, abundant shapes bespeak fullness even when they’re empty, while their large swooping handles invite the hand.

Belly Button Room Divider” prototype, 1957. Photograph by Brent C. Brolin, Eva Zeisel Archive

In 1958, Zeisel designed, for Mancioli pottery near Florence, Italy, startling and iconic wall and space dividers in glazed ceramic. These close-fitting grids of naveled shapes were a design failure—the pieces were too easily chipped to be used. This is a common hazard met by brilliant designers: their sculptural vision may make them lose sight of the practical purpose for which the object is being made. Forming beautiful objects within the creative constraints of cost, ease of manufacture, durability and practical use is what makes a person a true designer.

I dwell upon this particular design failure because if provides a visual key to understanding Zeisel’s work. The “swollen spindle” shape that is one of her trademark shapes, seen again the room divider, by its “belly button” makes its fertility symbolism explicit. Zeisel was so entranced by this daringly explicit shape it overwhelmed her usually excellent design sense. Clearly, it was a form that was meaningful for her.

And her delight in the shape is generally felt—this is one of her most iconic, eye-delighting forms. One wishes someone would produce it in plastic, lowering the cost and solving the durability problem!

The Royal Stafford One-o-One set—named for Zeisel’s one hundred and first birthday in 2007, the year it debuted at Bloomingdales, is distinguished by its repeating swollen-spindle shapes, familiar from the room dividers. These might suggest abstracted versions Asherah idols, the fertility goddesses with cylindrical bodies and protruding breasts, that feature abundantly in ancient Israel’s archaeology from the time of Solomon’s Temple.

Teapot, Creamer, Sugar and Salt & Pepper from the One-O-One set, Eva Zeisel Archive

Judaean female clay “pillar figurines”. Jerusalem, Beer-Sheva, Tel Erani (8th-6th BCE). Photo: Chamberi. CC BY-SA 3.0

Zeisel’s unconscious visual invocation of the divine feminine nearly breaks through to conscious awareness in this series’ iconic “Rockland Bowl” (named after Zeisel’s home in Rockland County, New York.) The stylized uterine cavity and upswept fallopian horns of this bowl, which could really only accommodate fruit or rolls as a serving piece, is audaciously explicit in its celebration of the feminine. A point which has escaped all male writers on Zeisel’s work, which can escape no woman who views it, though so far all have observed a politic silence.

Rockland Bowl from the One-O-One set,Eva Zeisel Archive

One of the keys to understanding Zeisel’s work is appreciating the physical femininity of her shapes. There is nothing unusual about this. Humans like human shaped things. We enjoy symmetrical objects, in part, because we are very happy to have two eyes, two hands, and so on. And male industrial designers show a preference for phallic shapes, in everything from weapons to vehicles, which is not entirely determined practicality and physics. So we needn’t be shy about recognizing the feminine and body-conscious element in Zeisel’s aesthetic. Part of what makes her work unique is that she asked herself questions about shapes in a way a man would not,

“When does something slim and graceful become skinny and emaciated? When does something rich, ample and voluptuous turn into just fat? When do emotions you want to convey become caricatures?”

Eva Among the Archetypes

Part of the power of Zeisel’s work lies in her unconscious use of the symbolism of water, of the moon, and of woman. This constellation of related ideas need not be discussed here at great length, since it is still so much with us. The moon’s monthly rebirth, its effect on the tides, the parallel between lunar and female cycles are clichés. Only slightly less commonplace is the analogy between the shapes of certain shells and the vulva, which accounts for their use by archaic peoples as charms to aid in birth or as grave-goods to assist the departed’s rebirth. This is the shell symbolism at play in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, in the status pearls enjoy as the archetypal feminine ornament, and the nearly universal use by scriptural religion of the pearl as a symbol for the wisdom that gains one eternal life, as in the New Testament’s “pearl of great price.”

The shell-like forms Zeisel created, the unornamented pearly glazes she favored, the lunar rondure her shapes, ranging from attenuated crescent to full orb, and the wavelike curves that flow throughout her opus, can all be viewed as moon-ruled. The simple fact that she was designing tableware, to present food, gives it an implicit relation to nurture, while the pitchers, creamers, and teapots, in shapes so often suggestive of water drops, carry the lunar into oceanic symbolism.

Zeisel’s most spectacular, one might say splashiest, designs, the Century line designed for Hallcraft, brings this to a crescendo. Her stacked large and medium platters, salad bowl and gravy boat,

Century Bowls, Photo Brent. C. Brolin, Eva Zeisel Archive

and her similarly liquid concentric series of dinner, salad, bread plate and ashtray,

Century Plates, photo Brent C. Brolin, Eva Zeisel Archive

with their ripple effect, are unambiguously aquatic. Of course these dishes would never be seen in such spectacular arrangement when it ordinary use, but their repeating shapes would make an equally real if subtler impression of family unity even spread across a table,

In the context of the sublimated female forms Zeisel created, which powerfully recapitulate the fertility figures of the ancient middle east, the water-theophanies of the Hallcraft Century line reveal a truly sacral dimension. When we bear in mind that religious altars begin as tables where food is prepared and shared, the reemergence of religious symbolism in tableware may seem inevitable.

Zeisel was herself an entirely secular person, and would have been amused at best to hear that she had recovered the feminine divine. But religious archetypes only gain freedom and power by being relegated to the unconscious.

One might make the case that Zeisel has recuperated the divine feminine in her work, in a particularly Jewish fashion. She has remained faithful to the Jewish resistance to images by abstracting them into symbols, into visual language.

Special thanks to EZ’s daughter, Jean Richards, for permission to use the EZ Archive photos, and for her valuable insights, helpful corrections, and gracious support.