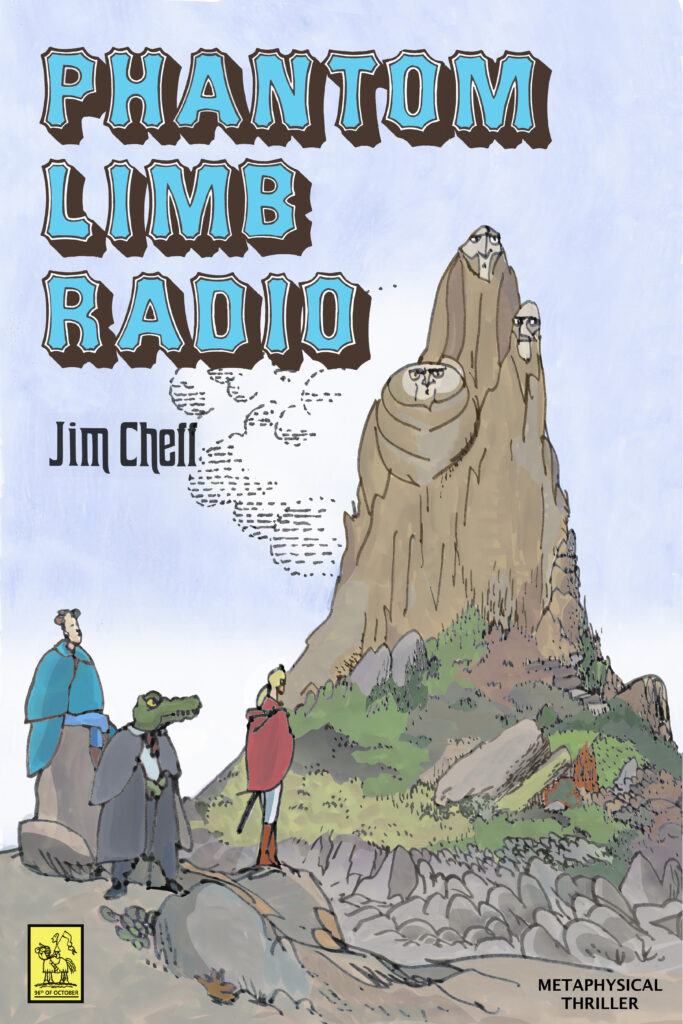

This is an excerpted chapter from Jim Cheff’s novella Phantom Limb Radio, the first book to be published by 96th of October. The title here is linked to the Amazon page.

Damn it! The alarm didn’t go off!

Or, rather:

“Damn it! The alarm went off and he didn’t hear it!”

His ears were buzzing, loudly. And he’d had that dream again.

The woman and the birds.

The small mechanical clock had exhausted its ringing more than an hour ago. Vayle Endlight opened his eyes long enough to check the time, then shut them again. He’d wanted to get an early start on the last leg of his journey, in order to reach Barrelslee before dark. He opened his eyes again and fixed his gaze on the now-silent clock. His vision held steady, with no rolling or shifting to the side. That was good. He shook the last traces of sleep from his head and sat up.

The rosy glow of the volcanoes was already being dulled by the white sun, a quarter of the way up the sky. The volcanoes rumbled and spat. They formed a smoky line of rock and redness to the south. He heard nothing of their grumbling.

From a distance, it might have seemed the man had slept with his head resting on his horse, which, with legs crossed beneath it, head held erect, had been very still for the duration of the night.

But a closer look would make it obvious that the horse was smaller than a regular horse, or even a pony. And no horse had ever sat so still for so long.

No, it was an artificial horse the man had used as a pillow. Now, in the daylight, one could see it was made of cloth and wire and yarn, knitted and stitched together from bright fabrics and ornaments. It was a hobbyhorse. Not a child’s hobbyhorse, but the kind one saw in village festivals, designed for celebratory and ceremonial use.

Vayle Endlight rose and gathered up the supplies and small bundles he’d assembled around the “horse” before going to sleep. Then he buckled himself into the artificial horse, wearing it at his waist, its decorated head pointing forward. He wore the hobbyhorse (he called it “the Rig”) like a big belt. Its body opened sidewise, hinged at the middle. Once it was buckled around his waist, he fastened the shoulder straps.

Endlight attached the “blanket” he’d slept under to the sides of the horse, so that it fell like a riding gown, down toward the sand. The riding gown bore a striking diamond pattern of red and gold. The Rig was less heavy than it looked. Endlight took off at a brisk pace towards Barrelslee.

From a distance—a much greater distance, now that the sun was up and bright in the sky— one might have thought they saw a man riding a horse.

Vayle Endlight tried to ignore the buzzing and hissing in his ears and listen to the sounds of the desert. He wasn’t listening for the usual sounds—the sharp cries of sand-hawks or the subtle coaxings of the wind against the dunes—but those other much-more-elusive sounds of the desert radio stations. He heard its vague voices at the edge of his consciousness, and sporadic bits of music—and there, just there, was it a fragment of disembodied laughter that he heard?

It was always hard to hear desert radio clearly though, and today his tinnitus completely overwhelmed its murmurs. Endlight wondered if he would lose the ability to hear the radio stations, too, when he completely lost his ability to hear the everyday, normal world.

Purposely goofy, and imposing in an absurd way, the Rig’s head bobbed as Vayle Endlight walked faster. Small bells jingled from the Rig’s fancy bridle.

When Endlight accelerated his walk to a trot, the Rig took over. Vayle and the Rig glided swiftly over the crusty terrain.

Vayle’s feet, toes pointed downward, skimmed over the Salt Flats, six inches off the ground.

Heading away from the volcanoes, Vale guided the Rig toward the Salt Flats, that great grey portion of the desert covered with ropy veins of glistening salt. The mountains that were his final destination were just a rocky scribble on the horizon.

His thoughts turned to the dream he’d had, and had been having, for weeks now: The woman and the birds. He’d been seeing the woman in his dreams for much longer than that. Since he was a boy. He never remembered them very well. But lately, the tone of the dreams had changed. Last night he saw the woman lying on a stone altar under a cloudy sky.

Birds circled, then descended.

The birds tore into her. She became a hot avian pie of birds, the vessel of their bloody internal nesting. They filled her with feather and beak and claw. They fed on her from within, they ate her hair from inside her scalp, they pecked out places behind her eyelids. They left her dazed, the color of ashes, sapped and exhausted.

It was a horrible, disturbing image, and he tried to put it out of his mind. But not the woman.

He tried to picture her face clearly for the millionth time, and failed.

Vayle glided more slowly through the last miles of the Salt Flats. He was now at the desert’s edge and past the reach of the desert radio stations.

He had only the insistent buzzzz of the recently begun tinnitus in his right ear and the familiar, quieter burrrrr in his left ear. The tinnitus rose and fell in volume. He had good days and bad days. This was a bad day. The mountain towns would be noisy when he got there and that would be hard to take if the tinnitus didn’t die down before he arrived.

But he had a few quieter stops to make before his ascent into the mountains.

The first of these would be the clockmaker’s shop.

At the base of the mountains, houses and small dwellings began to appear. He soon reached the clockmaker’s place. He handed him the alarm clock. Vayle Endlight’s clock was a handsome, box-shaped thing, wrapped on three sides in faded leather. Its face was burgundy and the dial and numbers were the color of sour cream.

“Lower the pitch, please, and make it louder.”

He’d made the same request the last time he’d been there. He was losing the higher tones, that was certain.

The clockmaker asked for no explanations and nodded, disappearing into his workroom. The two brass bells at the top of the clock would be replaced by two that were larger, louder, and lower.

While the clockmaker worked, Vayle Endlight searched his shop for useful items. Like most of the shops at the desert’s edge, it served more than one purpose. There were books here, and maps, along with other small items useful to the traveler.

Current maps of the Periphery were always of use. The shape and contents of the Periphery were always changing, and the mapmakers published revised maps as often as they could, hoping to keep up. Endlight studied the one with the most recent date of printing. He saw that Coomreedin had crept west since the last time he’d purchased a map. And new towns were appearing in the honeycombed hills near Diloxhyl. The once-towering realm of Serfendry had been sinking into the ground for years and now seemed to have sunken completely. But a new sand formation had been documented on the other side of the volcanoes. Endlight made a mental note to go there soon to have a look.

He scanned the changes in the dimensions of Whorsnest with less interest, having sworn never to go near it. He saw that its borders had bulged a little, but that should surprise no one.

Then Endlight turned his attention to the books. Books were among his chief pleasures in life, though he only carried a few with him at a time. A small collection was lined up neatly on a low shelf. Endlight chose one with an ornately engraved spine and slid it out from its station.

Ah—Pinapplio, The Pineapple that Yearned to be a Boy.

Pinapplio was a well-known fantasy tale, an old chestnut that illustrators were attracted to for its wild and risqué imagery. He read a few lines from its first page: “Pinapplio wanted nothing more than to be a boy; a living, real boy, instead of a pineapple. He yearned to tell the rude jokes they told, play their rowdy games, and experience the thrill of their childish conspiracies and ill-timed erections. . . .”

Vale left with the altered clock, the map he’d chosen, and a tin of hard mints for the friend he was going to see in the mountains.

The Rig bore him into the mountains. Endlight was, perhaps, a more impressive sight than he’d have guessed, with his cape and long blond hair, and decorated fake horse.

Behind him the volcanoes were now just a luminous fizz on the horizon. The abrupt and unlikely transition from arid desert to the lush mountain lowlands began in earnest, and the trail became subtly but unmistakably tilted upward.

He passed small farms. Then buildings of stone and impressive masonry became more common, finally culminating in the gabled roofs and chimneys of Barrelslee. It was just before dusk. Lamplighters were beginning their work. The streets were cobbled and he shared them with other travelers on horseback and in carriages. But most were on foot. There were apothecaries, rooming houses, a grain store, and several pubs. He saw several impressive fountains. Roofs were steepled and covered with curled orange shingles. It was late summer, and the city was full of bright flowers, lush, in striking contrast to the desert he’d left behind him.

The Rig drew little attention from the citizens of Barrelslee, as fashion or means of transportation. People rode all sorts of beasts and contraptions through the cities and outlands of the Periphery.

Vayle bore the Rig easily and steered its artificial equine head masterfully through the crowded places. Beneath the gown of the Rig, he walked as one normally would. Travel by means of the Rig—that is, becoming a passenger, a mere rider of its low skimming over the ground—took psychic energy, and more attention from Val than an onlooker might have guessed. In the vast reaches of the desert, letting the Rig “fly” was the best way to cover ground. But in places such as Barrelslee, it was easier to wear the Rig, but walk in the normal fashion.

He navigated the half-remembered streets until, without much difficulty, he found the Musetoreum. The Musetoreum was owned and operated by the friend he had come to see: Vaughn Earl-Royal, who had recently begun referring to himself as “The Pale Ontologist.”

Vayle Endlight rang the bell of the Musetoreum and Vaughn Earl-Royal appeared almost instantly. He was a slight man with a high forehead and rather long flat nose, with a pile of great bushy hair on either side of his head.

The two men greeted each other warmly, and Vaughn Earl-Royal guided his guest into the Musetoreum, which was only shown to visitors by appointment and was, but for themselves, empty.

Endlight detached himself from the Rig and left the hobbyhorse folded up neatly in the antechamber. Vaughn Earl-Royal guided him into the Musetoreum’s first gallery.

The centerpiece of the room was a huge and monstrous puppet head, with twenty bulging eyes and large box-shaped teeth. Great tufts of camel’s hair were fastened in patches to its chin. Green paint was peeling from the surface of the puppet’s angry face. At the top of each pointed ear was a metal ring big enough to put one’s hand through.

“I’m delighted you got here this evening, Val,” Vaughn Earl-Royal said, using the casual version of Endlight’s first name. “I’m having dinner at eight with a remarkable friend. I can’t wait to introduce the two of you.”

Vaughn Earl-Royal’s clothing was almost princely, but Vayle Endlight knew that Vaughn Earl-Royal came from modest beginnings. He favored the colors blue and gold, and his outfit was a clear illustration of that preference. He was wearing a periwinkle waistcoat, white breeches with gold buttons, and a short silk cape of very deep blue. The cape had a high collar trimmed with lacy gold ornament. Vaughn Earl-Royal’s sense of fashion was considered flamboyant even in cosmopolitan Barrelslee, whose citizens were used to the excesses of foreign visitors’ clothing.

Vayle realized that the gold his friend wore was artificial, as was most of the “gold” on display in the Musetoreum. Vaughn Earl-Royal had some wealth from an inheritance, but he was not rich. Nor did he make much money from the Musetoreum, nor were the items he found and curated there of any real value to anyone but a collector of the most rarefied sort of taste.

Earl-Royal guided Vayle Endlight past costumes on mannequins, smaller crumbling puppets under glass, and the spiked tail of what might have been a mummified dragon, toward his office in the back of the galleries. This was Earl-Royal’s inner sanctum, and it was where he kept the truly remarkable stuff.

Vaughn Earl-Royal’s inner sanctum was a small but well-appointed place, filled with curiosities and examples of recent advances in metaphysical tools and esoteric machinery. This was the part of Earl-Royal’s collection that anyone could see. His more serious finds were only for him and his close circle of friends. Vayle stole glances at items on the shelves he didn’t recognize, although he was sure that Earl-Royal would make him formally acquainted with them before the end of the visit. The walls were covered with masks of monstrous faces and the shelves were lined with fake constructions of all sorts of wild beasts. At the end of the pleasantly lit room was a papier-mâché replica of a huge dinosaur bone (Vayle guessed it was a femur). On a cluttered worktable next to it he saw a partially dissected Victrola and three imposing and ornate sound horns.

Vayle paused to look at a carefully sealed poster inside a thick frame on the wall. It was ancient, and one had to look closely to make out the faded image on the crumbling paper it was printed on. He knew the image, and the history of the poster. It was one of Vaughn Earl-Royal’s most-cherished possessions, dating back to the age of the Desert Mummers who’d once roamed the deserts, projecting mystery plays on giant stone screens.

The Desert Mummers were a vanished sect of powerful mystics who’d pioneered the art of “motion pictures.” The fake monsters and artificial cities Vaughn Earl-Royal hunted down and excavated were made by the Desert Mummers for use in their films. Hundreds of silent films were made by the Desert Mummers before they’d disappeared. Their habit, apparently, was to abandon the props and creatures they created after completion of their films, leaving them to be covered and borne away by the restless movements of the sand.

The life’s work of the Pale Ontologist was to bring these strange chimerical deities and artificial gods to the surface; to study and finally display them in the Musetoreum. Endlight knew there was a theater in the lowest floor of the Musetoreum where Vaughn Earl-Royal hosted rare screenings of the ancient films.

Earl-Royal had even recovered a few of the actual films of the Desert Mummers, but he kept these finds to himself and a small circle of friends. In one of those ancient films was the giant head displayed in the first gallery. It had been part of a complete puppet, twice the size of a human being. The rings at the side of its head were the fittings for two of the long poles that the puppeteers used to animate the creature, which Earl-Royal thought was a minor demon called Ursevus. Other non-human roles in the Desert Mummers’ motion pictures were played by small, animated models. They were animated using a fascinating technique called “stop-motion.” These could be even more convincing on film than the human-controlled puppets as they left no clues, on film, as to the artificial cause of their movements.

The Mummers had also devised means of combining these stop motion creatures with live actors, so that the invented creatures, though actually small models like the ones on Vaughn Earl-Royal’s display shelf, seemed to tower over their living human co-stars. The people of the Periphery, of the present or the past, had never seen the productions of a Melies or a Harryhausen, but if they had, they might have seen a similarity in their methods of making moving pictures.

There were rumors that the Desert Mummers killed the human cast of their productions after filming, but Earl-Royal said this was probably not true. But they did bury the elaborate sets and props and costumes from their productions in the vast sands of the desert, as soon as a film was completed.

Vaughn Earl-Royal’s obsession with the Desert Mummers and their creations was not simply that of an antiquarian. He was convinced that the Mummers were mystics of the highest order, and that the films they made were the summation of their understanding of existence, and all the forms of consciousness that emerged from it. The stop motion monsters and fantastic creatures in them were icing on the cake.

But back to the poster: the writing on it had crumbled and faded beyond reading. It seemed though to have been so ornate as to raise the possibility that it was not writing at all, but some sort of abstract imagery. The Ontologist said though it was definitely writing, most likely the title of the film and possibly where and when it could be viewed.

The illustrated portion of the poster had fared better. One could still make out a carefully rendered image showing a man in “wizard’s clothing,” walking down a mountainous incline, followed by six large, intricately decorated spheres. The spheres seemed to be rolling in a line behind the wizard.

Vayle remembered the first time Vaughn Earl-Royal showed him the treasured movie poster. “This poster was hand-painted, thousands of years ago,” Earl-Royal said reverently (although time was different in the desert, especially under the sand. Time was malleable, and in the deep desert, Time could change its mind about how old something was).

Val had peered into the faded pigment. The huge spheres that followed the wizard looked like children’s toys. They were decorated with swirling stripes, stars, and pinwheels. He imagined in its original colors the picture would have been eye-popping. The balls were the first thing one noticed in the picture, then the wizard, who seemed to be leading their way down the mountainous incline, in his tassel-belted robe and curvy-toed sandals.

The third thing one noticed was the dogs. There was a pack of rambunctious dogs running alongside the balls, which were twice the size of the wizard. The dogs were running gleefully, from what Val could make of the faded image. Their mouths were open and they seemed jubilant and lively. One had the sense that the dogs were pushing and herding the balls down the slope.

“It should be obvious what this depicts, Val” Vaughn Earl-Royal said, on that first night.

“Of course,” Val answered. “It’s the escape of Pin-Uthra.”

”Exactly!”

The story of Pin-Uthra was a famous one. It was one of the oldest legends in the Periphery. Countless books had been written about it—variations and interpretations, naturally, but all sharing the same basic elements. There were children’s songs about Pin-Uthra. Any doll or statue or picture of a generic wizard was called a “Pin-Uthra.”

Tonight, though, was not the time for studying the poster again. Endlight turned his attention back to Vaughn Earl-Royal, who was again promising that Vayle would be fascinated by the friend they’d be having dinner with. But he hadn’t gotten very far when he stopped and asked: “Val, are you hearing me all right?”

He had noticed that Val seemed to be listening to him with some effort since he’d arrived.

Vaughn Earl-Royal knew all about Vayle Endlight’s hearing problem. It had started ten years ago with a sudden and disturbing loss of hearing in his left ear. At first, Val could hear nothing through it but a roaring tinnitus and loud bursts of bizarre noises. Sometimes it was like the cracking of ice. Other times, the hum of a machine. And other times, loud, wordless voices, an insistent chorus void of content or meaning. Meanwhile the left ear’s ability to hear sounds from the real world was practically nil.

Eventually, these most unsettling effects of the hearing loss receded. But the left ear was left with a sharp and ever-present HISS that was with Endlight to this very day. The hearing in his left ear improved slightly, but what he could hear sounded flat and distant. Endlight adapted as best he could. He found ways to ignore the tinnitus, and he relied mostly on his right ear, with some small assistance from the diminished left.

He told Vaughn Earl-Royal that he’d recently suffered a second event similar to the first, this time in the right ear.

“I have to say it is maddening,” he confessed. “And considerably worse than what I experienced ten years ago on the other side of my head. If I cover my left ear—strangely, it has now become my “good” ear—what I hear through the right ear is far off and distorted, like a signal from a very tiny radio receiver. The tinnitus is loud, and the hiss on the left mingles with the humming and buzzing on the right in a totally unsettling manner.”

Vaughn Earl-Royal was uncomfortable with bad news, and while he could boast of a great social dexterity, his forte was not the comforting of troubled friends.

So he was relieved when Vayle Endlight’s said: “However, I have a plan.”

Then Vayle Endlight told Vaughn Earl-Royal what his plan was.

The clock chimed.

“Eight ‘o clock,” Vaughn Earl-Royal said. “We must leave for the restaurant. You’ll like my friend Maigraive, Val. He’s a most unusual fellow.”

The Pale Ontologist took Vayle Endlight to a lofty restaurant with a windowed dining room that overlooked the valley. Endlight followed him though the reception hall where there was a cage full of colorful songbirds. Their twittering sounded flat and off-key to him, and reminded him of the birds in his dreams. He hurried past them.

The dining room was all rich wood and shadows, and a fireplace glowed from the middle of the almost empty room. Night was falling, and through the windows they could see the other side of a deep valley. They could see the lights of a neighboring mountain town beginning to glow. Higher than that, the cliffs drew up and surrendered their details to the encroaching darkness.

Vaughn Earl-Royal led Vayle to the dining room, an enclosed balcony that looked out at the mountains.

One diner sat at a table.

Even if the room had been full, which it was not, Endlight would have guessed that this was the friend that Earl-Royal wanted to introduce him to. The diner was a large crocodilian, broad-shouldered and stout, who amiably raised a stein of beer in their direction as they entered the room. He sat in the chair in the manner that a man would, and he was dressed as a man, too, in a full suit with vest and burgundy cravat, made of a cloth Endlight could not name, but felt certain was expensive. A dark cape was thrown over the back of the crocodile’s chair. His mouth was open in a reptilian half-smile that showed a fearsome set of conical teeth, and beneath the immense lower jaw was a bulbous and jowly throat, out of which the crocodilian croaked a jovial “good evening.”

Earl-Royal led Vayle to the table with obvious satisfaction and made the introductions. He introduced Vayle to the crocodile first, then followed with: ”Vayle, this is my illustrious friend, Cassius Maigraive.”

“Delighted!” Cassius Maigraive growled, extending a scaly hand toward Vayle. He added, “I have never regretted meeting a friend of the Pale Ontologist.”

Like most people, Vayle Endlight had never met a crocodilian. But he knew a thing or two about them, as they were the stuff of legend in the Periphery. A crocodilian’s life—at least the long first half of it, anyway—was spent in battle, far beneath the surface of the mad city of Whorsnest. Only late in life could crocodilians leave the war behind and make the hard climb to the surface, if they did not perish first in their eternal, subterranean war.

After they’d taken their seats, Vaughn Earl-Royal said to Maigraive: “Val is undoubtedly excited to meet a crocodilian, and is definitely bursting with questions. But he’s far too polite to ask them outright. Lest he dance around his curiosity the whole evening, let me impose on you, Maigraive, to tell us about your unusual life, and of course your experience as a crocodile soldier.”

Cassius Maigraive nodded good-naturedly and settled back into his chair. “Of course! I would be glad to. To begin with recent history, I came to the surface three years ago almost to the day. Since that emergence, I have made it my business to tour the Periphery as much as possible and learn its many ways. I have sought to experience as much as I can, in as many places possible. Most recently, I visited the great Fissures of Kazkdan. You may have heard of them. Great splits in the earth where Knowledge itself rises up in steaming clouds! Scholars flock there to bask in the fumes and soak up as much as they can. Indeed, I found myself growing smarter by the day! But I only stayed a short while.”

“Why is that, Cassius?” Val inquired.

“I grew tired of their wise cracks,” the crocodile said with a straight face.

Then he tilted his head back and laughed.

Endlight had long considered puns a disappointing form of humor, and he felt that brief letdown at hearing an interesting story suddenly deflated as the set-up for a joke. But he nodded in recognition of the crocodilian’s play on words.

The crocodile’s opening remarks bore out one part of their legend: they were irrepressible fans of puns, jokes, and comical narratives. It was a remnant of their years of battle in the wet, jam-packed tunnels beneath Whorsnest. Their turgid, clawing warfare took forever, so packed in were they, so while clawing at each other they would tell these stories and jokes to pass the time. Crocodile wars were more an endurance contest than a battle, for there was no apparent goal, no objective, no hill to take, no flag to plant, using stories and puns to pass the time as they tore and bit at each other, while Whorsnestian citizens, far above—their plumbing clogged by the subterranean conflict—cursed their plugged up sinks and toilets.

Crocodiles were soldiers in the young adult stage of their mythic lives. Later, if they reached a full maturity, they would climb their way out of the vast network of plumbing beneath the city. Once in fresh air, they sometimes matured into erudite retired warriors, done with warfare but still fond of the old verbal games they played for so long.

Having just witnessed the crocodilian fondness for puns and plays-on-words, Endlight had a sudden (and correct) intuition that it was Cassius Maigraive who had cleverly combined the two passions of his friend Vaughn Earl-Royal—his love for abstract musings on the nature of Being and his equal passion for the digging up of ancient things in the desert—into one amusing nom de plume—The Pale Ontologist—which reflected his passion for ontology, and his own peculiar form of paleontology. Adding to its cleverness was that it also took on a descriptive dimension, considering Earl-Royal’s ghostly complexion.

Thus began a complex and lively discussion as they waited for their meal.

Vayle Endlight and Vaughn Earl-Royal were studious types, and the topics they introduced had to do with ideas. Cassius Maigraive was of a more earthy nature, and his contributions had more to do with news and experiences of the world.

After only a little conversation, Val reversed his first impression of the crocodile. He found him quite impressive, indeed.

We might privately wonder, during the course of this three-sided conversation, at the erudition of the crocodilian—considering he had only joined those on the surface of the Periphery a few short years ago. Cassius Maigraive had quickly defined himself as an inexhaustible source of gossip, trivia, and indeed bona fide scholarly knowledge, before the first course of the meal had been served. But his knowledge of the surface world was not so great a mystery as it might seem to some. For the sewers, packed with waste from the denizens of Whorsnest, was a vast informational network of excrement, from which the crocodilians, miles of pipes and plumbing below, absorbed the thoughts and ideas of those who shat into it. One might well become the sort of good-humored scholar that Cassius Maigraive appeared to be, through a lifetime of judicious and well-considered absorption of shit.

This leads us to consider—hastily, before the food arrives—the waste management situation of the wretched city of Whorsnest. While it was true that Whorsnest was a cauldron of ignorance and depravity and the worst that the human recipe could result in, it was also true that among its captive citizens were intelligent and educated souls. The thoughts of these tortured souls were what Maigraive had built his emerging psyche on. Their hard-earned education was what took root and flowered, eventually, in his crocodilian mind.

The higher demons—the torturers—of Whorsnest did not use the plumbing at all. Otherwise, only madness and evil would have made its way down to the crocodiles. It was said that the feces of these lunatic flying monsters detonated upon expulsion, and atomized, becoming one with the very molecules of the air which the lesser citizens of Whorsnest breathed.

You see? Whorsnest deserved its awful reputation.

At any rate, this was how it was possible, and common, for crocodilians to “educate” themselves, in a second-hand way, from the city that existed above them. There were soldiers who, once retired, climbed happily up to Whorsnest and stayed there. But there were others, like Maigraive, who left the city, and most of its madness, behind them.

And here is the food.

Two waiters brought out platters of roast turkey and spicy gravy, and there was schnitzel and baked potatoes and roasted greens and asparagus. A loaf of black bread was placed within the reach of all three diners, and dishes with slabs of fresh butter. More beer and tall glasses of cold mineral water.

If the crocodile really had spent most of his life in the sewers, he looked and smelled no worse for it. His clothing was clean, and if any scent came from him at all, it was of beer and a subtle but robust cologne. His table manners, too, could not be faulted. He took care to sit back in his chair, so as not to crowd or menace anyone with his long snout. And he handled the silverware with great dexterity, placing the food sidewise into his mouth just at the corner of his great jaws.

Maigraive’s exposition on the life of a crocodile soldier was just ending.

“The crocodile war beneath the surface is a cosmological fact. There is, perhaps, no explaining it. But to deny the reality of it is not an option. I myself am living proof of its reality. We are born in the sewers, we fight there, and some of us live long enough to leave the sewers and claw our way to the surface. One “reason” for the whole affair, that I will share with you now, has been proposed. It has been said that the subterranean war of the crocodiles, the primal heat of it, its lack of ending, is a power source, a sort of engine, that fuels existence on the surface. That its raw brutal power and intensity is the engine of this higher plane of reality. This explanation, if true, makes our war the foundation of the creation of higher worlds. It casts the whole thing in a Divine light. The point of our warfare may be the realization of higher worlds.” The crocodilian asserted this with pride.

The Pale Ontologist said “You appreciate honesty, Cassius, so I’ll say it outright. Crocodiles, wrestling in a sewer full of shit, does not strike me as Divine.”

The crocodile took the comment in stride. “Alas, it is the life we’re born to. An ugly life, perhaps, but it is ours. The fortunate among us find the Divine in what we’re given.”

They clinked glasses. Vayle recognized it was the good-natured sparring of close friends. (And shall we call Vayle “Val” from now on, too, now that we’ve gotten to know him better?)

Vaughn Earl-Royal decided it was time to change the topic.

He leaned in toward Maigraive and said: “Val’s got the most extraordinary project in the works.”

“Does he?” the crocodile asked, very interested. Val however felt a jolt at Vaughn Earl-Royal’s blunt and unasked-for introduction to Val sharing his plan. It was one thing to tell it to Earl-Royal a few hours ago, in the privacy of the Musetoreum. But he had only known Cassius Maigraive a few hours.

He knew that Vaughn Earl-Royal was proud of his friends’ eccentricities. Was he trying to impress Maigraive with the unorthodox nature of Val’s thinking, and Val’s new, admittedly audacious, response to his hearing loss? Earl-Royal had, after all, beamed, when he surprised Val with an unexpected dinner with a crocodilian soldier.

But, what of it? Cassius Maigraive seemed like a deep and unconventional thinker, and not without his share of unusual knowledge. He might have something useful to add to Val’s plan.

So he leaned toward Maigraive as well and spilled the beans.

He told him about his tinnitus, the vertigo, and his rapidly declining hearing. Cassius Maigraive had, in fact, noticed that Val seemed to be straining to hear the conversation at times. And there were a couple of times he was certain that Val hadn’t caught something that was said and merely pretended that he had. “I’ve consulted doctors of both the scientific and magical disciplines, with no results. Artificial ears and potions have done no good. Hearing trumpets only make me look silly. To be honest, the situation has caused me a great deal of unhappiness.”

“No doubt,” the crocodile said.

Magic and Medicine were on mostly equal footing in the Periphery. Both Magic and Medicine were for the most part crude and unreliable callings, and both had their share of quacks, cure-barkers, and con men. Both doctors and witches preyed upon the desperate and gullible, and many suffering people saw both professions as a last resort. But of the two, Magic was the most popular approach to things in the Periphery. It was the experience of all three diners in this conversation that non-ordinary means were the best solutions to both physical and metaphysical problems.

Val Endlight had abandoned the practice of consulting doctors about his hearing loss and had come to consider more fantastic ways of combating it. But magic had failed him in this regard as decisively as science.

“Having tried a variety of spells and enchantments and consulted witches, oracles, and magicians of many persuasions, none of whom were able to stop the deterioration of my hearing, I have imagined a way of exploiting the dimensions of my apparently incurable and progressive loss of hearing. To adapt to it, with gusto!”

Val leaned forward. “Have you heard of the phenomenon called the “phantom limb”? Cases where a person loses an arm or leg, through amputation or accident, but after recovery from the loss, continues to feel pain and sensation in the missing limb?”

The crocodilian nodded from the other side of the table. Of course, Val realized. Of all the diners in the room, it was Cassius Maigraive who was most likely to be familiar with it.

“In the sewers, many of us lost limbs. I remember the complaints of soldiers who felt tingling, or outright pain, in limbs they’d lost, years before.”

“I am told that tinnitus—the maddening hiss I hear in my damaged ears each day—is a form of the phantom limb phenomenon,” Val said. “The brain seeks to supply information to an area that is suddenly void of it. Tinnitus is the phantom limb of the inner ear. What vacant space is left by a loss of hearing is filled by the roar and hiss of tinnitus, courtesy of the brain.

“But why does the brain throw garbage in? The brain is a versatile and some say mostly-untapped organ. Why can it not fill that space with something more valuable?”

“I see,” said the crocodile. “You would ask that the brain, your brain, fill the vacuum of your deafness with something more than auditory nonsense.”

It was the idea that Val had explained to Vaughn Earl-Royal earlier in the evening. Earl-Royal found the idea audacious, but interesting.

“Look at the desert radio stations! They pull their sounds and voices from the ether; some would say the Sourceworld itself. Can my brain, my very advancing deafness, be made to do as much?”

Maigraive nodded. Val was clearly modeling his project on those desert radio stations which, theoretically, pulled signals from the Sourceworld and the DreamSuck, and broadcast them to able receivers. (The DreamSuck was supposedly made up of fragmented consciousness emanating from the inhabitants of the Sourceworld, though the existence of both of those realms had never been definitively verified.)

It could not be disputed, though, that the mysterious radio stations did pick up signals from somewhere.

Considering this, Cassius Maigraive allowed that Vayle Endlight’s plan for erecting radio towers in the wilderness of his own psyche was not so absurd as might initially seem.

Val imagined the current state of his hearing as a tilted, asthmatic antenna on a plane of bare rocks and scrub-grass. This antenna was the source of the Hiss, the Tinnitus—could that tower be re-imagined, tilted upright, energized, medicated, corrected, to broadcast something more than loud, empty air? Could a radio “station” be connected to that tower, one that offered more than sonic gibberish?

“I am proposing that my ears—the very deafness of them—become a radio receiver. . . . ”

“A phantom limb radio station!” Maigraive said, finishing Val’s thought.

“Yes!”

The Pale Ontologist thought Val’s idea had merit, and he could tell that Maigraive thought so too. For the Ontologist, the thing that made it compelling was its use of the brain. No other organ—through inspiration, injury, or distress—was capable of producing such varied and intriguing responses. The stomach, liver, intestines, et cetera, were all mere sacks of blubber by comparison. Their knee-jerk responses to stimulus were so boring and unimaginative! Those organs interested Vaughn Earl-Royal only when they caused him discomfort.

The brain, on the other hand, was an unexplored continent, a world even, and the things it could yield when courted and enhanced by its owner were prodigious. He thought first of drugs, of absinthe, of the hallucinatory mushrooms that were traded and revered in the mountains. Also, there were those confounding maladies that could be traced back to the gray organ, and the peculiar effects they produced in the afflicted.

Val’s idea had reminded Earl-Royal of his mother, who had slowly gone blind. She had experienced a strange altering of her perceptions in the later stages of her deteriorating eyesight.

To support what Val was describing to Maigraive, Earl-Royal shared this anecdote:

“As my mother’s sight deteriorated, leaving large gaps in what she could see, but also leaving fragments of her vision intact, she began to see in the ‘blank spots’ things that were not there. For example: When we looked at photos, she would see those who actually were in the photograph, but others who weren’t in the photo as well. She would insist that a picture of two people was actually a picture of three.

“As her blindness progressed further, she began to see two girls in fancy dresses in her living quarters. The girls were silent and non-threatening, and she came to enjoy their occasional presence. Especially as those people around her, of the ‘real world,’ had been reduced to dim shadows.”

Val was familiar with the tale. “A very similar thing to the predicament of my own brain, filling my head with the Tinnitus. But I would ask that my ‘two silent girls’ speak. And who knows what they might tell me? Or what unearthly song might they sing? I would ask more, in exchange for the loss of my hearing.”

Vaughn Earl-Royal observed: “Val is always looking for information! My mother was only seeking companionship. She was quite satisfied with her two silent girls.”

Now that the plan had been discussed, Val was delighted that Maigraive, who seemed a no-nonsense sort, was not dismissive of it. Maigraive seemed to not only find his idea intriguing, but delightful—in a mad, improbable way, of course.

“The Improbability Factor is, naturally, a part of its projected success,” Val said to the crocodile.

“It would have to be,” Maigraive affirmed. “I would advise avoiding even the smallest concessions to good sense in the pursuit of this goal. Stick to the preposterous and it may work!”

The dining room had filled up since they had arrived, and the conversation in the room was becoming hectic and confusing to Val’s beleaguered ears. He excused himself for the restroom.

“Your friend is quite mad,” the crocodile said to the Pale Ontologist once Val had left the table. “I could become fond of him.”

For some reason, public lavatories were a bizarre affair in the Periphery, each with its own confusing rules of etiquette and behavior. More often than not, using one was not worth the embarrassment and the exertion of social dexterity that was required. He was relieved to find that the situation here has simple and forthright, and also that he was the only visitor.

Val stepped up to the urinal and released the kraken.

Minutes later Val was back with his friends in the dining room. Night had fallen completely, and the mountains were covered with glowing dots, and the drifting fireflies of balloons and airships.

Vaughn Earl-Royal was feeling pleased at the combination of his two friends, Val and Cassius. They seemed to get along admirably. Earl-Royal, who considered social matchmaking a talent of his, was proud of that the combination of Endlight and Maigraive appeared so promising.

Beyond that were those secret hopes he had of what would come of making the introduction. His next and most exciting project to date depended on the cooperation of both Val and Maigraive. A darker thing flickered in his mind, the thing he feared would make his proposal dangerous for all of them—but he pushed that dark misgiving aside. He sipped his beer and sparred amiably with Maigraive until Val returned to the table.

Val got another look at Cassius Maigraive as he found their table again. This time Val noticed the powerful ridged tail of the crocodilian, curled sidewise from the chair and extending downward to disappear under the table.

Val mused that Cassius Maigraive could probably have killed all of the diners in the restaurant in a manner of minutes, and eaten half of them in the same amount of time. He had noticed guests at other tables sneaking uneasy looks at the retired reptilian warrior. But Maigraive had done nothing to suggest he was anything other than the most jovial and well-mannered diner in the room.

They had dessert. Raspberry tortes were brought to them on a silver plate, along with a variety of wrapped chocolates.

Late in the evening—when they had talked of psychic radio stations and the theory of derivative worlds and silent, imagined girls and mysterious signals in the desert—the Pale Ontologist, Vaughn Earl-Royal, gave his reason for calling his two friends to this meeting.

“After much research and inquiry,” he said, “I have come into possession of a map. As you both know, the driving passion of my work is the reassembly of the works of the Desert Mummers, primarily based on the recovery of their films and the props and mechanisms they used to create them. I am now certain of the location of some abandoned props from the creation of their greatest film (it is said, though I have never seen it) ‘The Escape of Pin-Uthra.’ “

“The magician?” Maigraive asked.

“The wizard,” Vaughn Earl-Royal corrected.

He continued. “Conditions of the A.F.O.M., and the unstable dimensions of the Periphery, have long made the recovery of these artifacts impossible. But these conditions have shifted. The artifacts are now within my reach, and the map could be followed to them by a modest expedition of just three adventurers. I propose that the three of us are that trio.”

“And what would we be looking for?” Maigraive asked. “A papier-mâché Cyclops, or a painted backdrop? I hope there’s no digging involved in this scheme. . . .”

“The spheres are hidden in easily-accessible tunnels, Maigraive. Not buried.”

“Spheres?” Val said. He remembered the decorated spheres from the poster in Vaughn Earl-Royal’s Musetoreum.

“The same,” the Ontologist confirmed. “What a find, eh? The film itself has eluded me for decades, but to have the spheres created for its production would be amazing!”

“Can you be certain of your information, though, Vaughn?” Val asked.

“I have it on the highest authority.”

Val nodded. He knew that Earl-Royal was a master of research, with a whole network of eccentric but highly educated friends who might well know about a thing like this.

“How modest an expedition are you talking about?” Maigraive wanted to know. He knew the Ontologist’s modest projects often grew prodigiously in the course of being pursued.

“I can show you,” the Ontologist said, removing a folded map from the pocket of his cape.

He spread it out on the table. The complex map meant nothing to either Val or Cassius Maigraive.

“We can be there and back again in a month’s time,” Vaughn Earl-Royal said, running his finger over a crazy quilt of lines and instructions. After we leave the desert we will have to travel A.F.O.M. But Val and I are up to that, Maigraive.”

Traveling A.F.O.M. was a paranormal method of enhanced travel through the real world. It was difficult, even for those few who were able to do it. Navigation through A.F.O.M. territories was notoriously demanding.

“This route is far beyond my skills, Vaughn,” Val said.

“But well within my own,” Vaughn Earl-Royal replied.

“The map is written in your own hand,” Val observed.

“Yes! I copied it from the original, which I have put away for safekeeping. But rest assured, Val, this map is not guesswork or supposition on my part.”

Maigraive said “Seems like a lot of work for some props from an ancient motion picture.”

But he said this mostly to annoy Vaughn Earl-Royal.

“Work? I speak of adventure!” the Pale Ontologist cried. He said it with such panache that a sleepy waiter, anxious to shut down the restaurant for the night, looked over.

From down the hall Val heard the tinny chirping of the birds.