Since 2009 Doron and Yoav Paz have made four movies (Phobidilia, ,JeruZalem, The Golem, and Plan A) and four TV series (Exposed, Asfur, Temporarily Dead, and Fullmoon). The Golem and JeruZalem are currently available on Amazon Prime, Phobidilia (title is linked) is on Vimeo.

The Trailer for JeruZalem

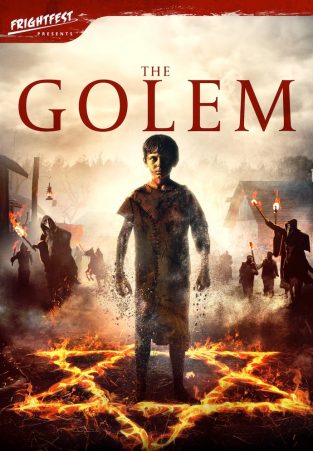

The Trailer for The Golem

It’s well worth making the detour to see Phobidilia before you move on to The Golem and JeruZalem. This was the Paz brothers’ first film (2009), and it shows the depth of cinematic vision that makes their horror films fascinating. Phobidilia is an offbeat love story about an agoraphobic computer geek, and how the outside world impinges on his careful self-isolation through his landlord, a paid Internet “girlfriend,” a real girl who stumbles upon him, and the omnipresent television. The story is told with considerable humor, empathy, and marvelous visual playfulness. If you enjoyed the droll outsider heroes of Fleabag, Flowers, and The End of the Fxxxing World, you’ll find Phobidilia a discovery. And it includes a dimension of visual play that puts it on a whole new level. I believe we have real future auteur film makers here: a strong claim to make on the basis of a first film, but one that I’ll warrant will one day appear as prophetic common sense.

Yoav was unavailable, so I was only able to speak with Doron Paz. He says “we” because he and his brother work completely as a team in every aspect of the film making. Anything in square brackets in the following is information I have added.

96 The Golem (2018) was filmed in Ukraine, with beautiful nature scenes and the authentic looking Eastern European rustic buildings—dark wooden structures with high steep roofs—originally built as the set for a Russian TV show. Magnificently photographed by Rotem Yaron, it features a stunning performance in the lead role by Hani Furstenberg

It’s a very complicated movie, and a very ambitious one. You dealt with the theme of anti-Semitic violence, without trivializing it into entertainment, or allowing real-life horror to overwhelm the fantasy terror of the film. How did you decide how far to go, how much was enough, how to integrate it into your narrative?

DP Politics is always there in any movie, but The Golem is not really political. The idea was to bring the myth of the golem, which is our own Jewish Frankenstein, to life. My brother and I like horror movies; we wanted to do another one after JeruZalem. We thought of the golem, began researching it, and found that the last golem movie was made over a hundred years ago; I think it’s twenty minutes, black and white. [The Golem, 1915, Dir. Wegene and Henrik Galeen, silent, partially lost.] There are movies about the dybbuk, and other Jewish mythological themes, but nothing about the golem. We thought, great, here’s our horror movie. We wanted to take the audience to the Kabbalistic dark side of Judaism—not the usual Fiddler on the Roof shtetl—to something more complex.

It’s a great story, bringing a creature to life out of mud and prayers.

96 So you saw the background of anti-Semitism as somewhat peripheral to the story, a factor but not a central one?

DP It’s there, and we dealt with it, but it’s in the background, it’s not the issue of the movie. What interested us was the isolation of the shtetl from the outside gentile world, for better as well as for worse. The bad side was the hatred they experienced as outsiders. The good side was the independent development of their own traditions and culture and, as in the movie, their separateness could keep them safer in outbreaks of plague

96 You also dealt with the central character, Hannah’s, ambivalence about childbearing after the death of her child. Hani Furstenburg’s performance gave Hannah great depth.

The script also develops her in a way that makes it seem as if she’s the real demon here. Her calm and poise became positively frightening shortly after the golem killed the rival for her husband’s affection. At the dinner scene the Hannah character was so eerie, I was scared. I was wondering whether she hadn’t made the soup from her rival’s heart. How much of that terrifying dinner scene was in the script and how much was Furstenberg’s free interpretation?

DP It was in the script of course, but Hani is an amazing actress. She left Israel years ago, and we had no idea whether she would take the role. She was in Israel for a few weeks, we sent her the script and asked her to read it, maybe meet with us. She heard the title, that it was a horror movie, and—no, thank you! She thought it was another serial killer running around with a knife. She made an appointment with us, and stood us up. Then when she got back to New York, she read the script carefully and realized it wasn’t just another horror film. She wanted the part. We were lucky to get her,. She’s amazing.

96 It’s a very rich role and she did justice to it. The film is really a drama in a supernatural framework.

DP Totally. We wanted to do something very different from JeruZalem, which was our second feature film. The plot there was very simple. Zombies in Jerusalem, you need to survive. The end. Now we wanted something more complex, and I think we succeeded in giving different layers to The Golem. On the surface it’s horror-genre entertainment, but when you get into it, it addresses themes of motherhood, relationships, couples, mothers, and sons. It’s not the usual.

96 I know you like to think of the film as a variation on Frankenstein, and that’s certainly part of it, but it really made me think a lot more of Carrie. It opened with a woman having woman’s problems, and the next thing you know her feelings are killing people. Men’s primitive fears regarding women seem to me to be a subtext in both films. Do you see that in your film? Have any female viewers commented on it?

DP I never thought about Carrie as a reference; I guess it’s there somewhere in my head. I saw it many years ago.

I think we seriously engaged the hidden and conflicting feelings of the female main character, and onscreen violence expressed the intensity of what she felt.

96 I thought your handling of the supernatural element was amazingly skillful. The way you alternated between realistic special effects for the golem’s supernatural power, as when the dismembered limbs of Hannah’s attackers are flying, alternating with shots of the weirdly calm human child who played the golem. This was a balancing act between realism and symbolism. It seemed like I was seeing more than I was seeing.

DP The secret of that was this child actor we found, this local Ukrainian kid who didn’t know a word of English. Luckily for us the golem child is not a speaking role. I think it was his first role, though he’s gone on to do more work in Ukraine. He was so disciplined and so professional. What captivated us was the contrast of his cute, unlined innocent child’s face, and what he was able to do with his telekinetic powers. Our work with him was simpler than with any of the other actors. The golem is not an emotionally responsive being, so my direction was pretty mechanical. I’d just say, through a translator, “Stand here, walk there, pick up the doll . . .” He was so cute and heartwarming, and the weirdness of that in the role worked.

96 There are two scenes in The Golem I’d like to know more about. One of the most powerful scenes in the movie was the one where Hannah breaks into the synagogue through the floorboards: it’s like a birth scene, like the bursting of an egg. How did you come up with that, and how did you make it work?

DP We wanted the metaphor of the woman being reborn, getting new strength. We actually had to dig a huge hole for her and the cameraman and build the floor she burst through; it was quite a complicated scene. Luckily for us the Ukrainian art department we had working for us was amazing. It was, like, thirty guys, and they built this whole synagogue

96 For me the most amazing scene in The Golem was where Hannah is in bed with Benjamin, just their heads, side by side on the pillow. Her red hair suggested blood more than the actual red droplets that then fell from the ceiling. It made me think of Edvard Munch’s painting The Vampire. How did you compose that image?

DP I have to admit, I wasn’t referencing that, but you see so many images nowadays with computers and movies, without being fully conscious of them. I know the painting you mean, and I wasn’t consciously thinking of it for that scene, but who knows?

That scene took us a very long time to shoot with precision: we had to find the right angle, the drops of blood had to hit at the right moment, the kind of cloth on the pillow so they’d show up correctly— it looks like a simple shot, but it was quite complicated.

96 It was worth it. The shot was unforgettable.

The Golem ends with the literal and symbolic return to dust of the golem. You showed the dust blowing, but you didn’t actually show the golem child dissolving, yet somehow the images worked together and I believed I was seeing more than I was being shown, maybe because I understood so clearly what you meant. Why did you make this choice rather than using CGI?

DP I think every director prefers a physical effect to CGI. The physical and real is always better. In JeruZalem we made wings for the creatures and animated them, but it wasn’t the same as the physical actor in the makeup. We knew we didn’t want a computer effect when the golem child dissolved. We wanted it to feel real. We tried different materials to produce the dust, the smoke.

Also, we wanted the focus to be more on Hani Furstenburg then on the dissolving child The focus needed to be on her, her hands, her expression. We wanted to be with her when her reborn “child” died, not with him.

96 These choices of yours, which I think are wonderful, remind me a little of the Hong Kong supernatural movies of the 80’s. They hadn’t completely made the transition from the conventions of the theater to those of film. Did you have theater experience before you got into film?

DP Our grandfather was a theater director, so we grew up with that, of course. But theater doesn’t really speak to me emotionally as much as film does. But theater and film will always have a family relationship. Some of the sets in The Golem could suggest theater, I can see how the influence of our grandfather might be there.

96 I admire your restraint with the use of CGI. Often when I see CGI sequences, my mind wanders from the film, because they didn’t leave any room for me to participate in the experience.

DP Exactly. What really makes a horror movie scary is not what you see, but what you don’t see. Do you know the horror movie Mama?[Dir. Andy Muschietti, 2013]. It’s a good film, you should see it. For half of the film you only imagine the monster, you see its footprint, you understand it’s playing with the kid. Then about halfway through you start seeing the monster, CGI, 3-D model, just in-your-face, and from that point on you’re not scared. For me it’s a good example of why a horror movie should allow space for the imagination, not show too much.

96 The Dybbuk is the all-time classic Jewish horror story. It first appears as Shloyme Ansky’s 1916 play; the great modern Israeli poet Bialik translated it from Yiddish into Hebrew, it was made into a not-terrible Yiddish language movie in 1937. Can you see yourself making your own Dybbuk?

DP (laughs) I don’t think so. When we found we had this great location in Ukraine, we immediately thought about The Dybbuk. We started reading, researching it, and we found it’s really been done, there have been recent movies about the dybbuk.

We’re very drawn to the dark Kabbalistic side of Judaism, so we can see ourselves doing more in this genre, but the dybbuk? Not unless we can come up with a really fresh and interesting take on it.

96 Let’s talk about JeruZalem (the capital Z is for Zombie). The film is obviously drawn from the life: the bimbo tourists, the smooth talking Arab guides and hoteliers, the shots of the Old City, the fascinating shifting prospects of narrow stone streets as you see them when you’re on the move and you know where you’re going, never a static tourist view. And when the crisis begins, with the explosions and the warplanes roaring overhead, you made the tension rivetingly real. I’m assuming you drew on memories of actual military experience.

DP In the army I was a tank commander; my brother Yoav got the good job, he was in a film unit. Maybe I drew something from that. But JeruZalem is a “found footage” movie. “Found footage” is not easy, but if you do it correctly, the potential for realism and the feel of authenticity is very high. You can pull the audience in really fast because it’s so natural and the director’s manipulation is so minimal. We wanted it to be as intense as possible. Jerusalem is a very intense city, and that carries over into the film.

96 Most of the film is seen through one character’s Google Glasses, so computer info, and later, computer glitches, make a chaotic counterpoint to the progressively crazier narrative [literally crazier, part of the action takes place in a madhouse]. From the time of Terminator, we’ve seen computer information scrolling by in a character’s POV shots, but I’ve never seen a whole film done with a computerized echo effect like that. You very clearly appreciated the humor and irony of it, introducing the motif of computer games with swordsman versus zombies at the beginning, and repeating it for real at the end. Dark humor worthy of George Romero!

Was it as much fun for you to script and film the Google Glasses motif as it was for me to watch?

DP We wanted it to be entertaining and funny, not just hardcore horror. What we liked about the Google Glasses was they added another layer, a social-media layer, which made it possible to tell the story differently.

96 For me, the magic in Jeruzalem was in the quick, strobe-like glimpses of the supernatural action. The scenes of the bat-winged zombie demonic undead were visually telegraphed. It made the speed of the creatures’ attacks seem more than fast. They’re there, then they’re there, then they’re closer, then they’re here—it’s like they are not limited by the laws of space. It’s like they move in pure time. There was something similar in The Grudge.

DP Well, they’re not time travelers, they’re not teleporting. I think that’s an effect of the “found footage” sub-genre. The vision there is very limited, the point of view is narrow. When you move the camera, the whole atmosphere can change. When you’re making a traditional film, you know where everything in the scene is. In an intense “found footage” horror movie, you can play with it. Chaos works for you. “Found footage has its own specific laws—for better or worse.

96 What’s your next project?

DP We just finished our fourth feature film, called Plan A. It was done months ago, but COVID stopped everything. It should be out in the second half of 2021. It’s a historical thriller, a true story, about a group of Holocaust survivors trying to kill six million Germans. It’s a true amazing story no one’s ever heard of. It’s the greatest revenge story in history. They came very close to succeeding before the Allies stopped them. It stars August Diehl from Inglourious Basterds and Sylvia Hoeks from the new Blade Runner. We can’t wait to bring it out.