Bullied By Mondrian

The Aesthetic movement (which you’ll call Symbolism or Decadence if you took French in high school) occupied the second half of the nineteenth century. It was a reaction against industrialization, the rise of scientific positivism, and the mania for moralizing that provided a sugar coating for what all that progress actually implied.

In more concrete terms: a late nineteenth-century man actually lived in in an urban world of mass-produced goods and mechanized warfare. He averted his eyes from that grim actuality and fixed his gaze upon sentimental narrative paintings with heavy-handed moral themes.

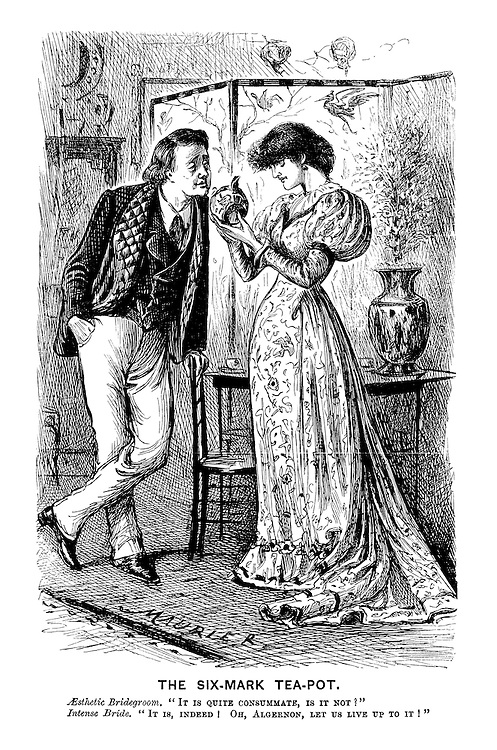

The Aesthetic movement responded by prizing craft-production, mysticism, and an art that was purely aesthetic in its aims. The aesthetic credo was amusingly summed up by Du Maurier in the 1880 Punch cartoon reproduced above, which shows an “aesthetic” bridegroom saying of a high-priced teapot “It is quite consummate, is it not?” to which his “intense” bride replies “It is, indeed. Oh, Algernon! Let us live up to it.” The cartoon couple are acting out Walter Pater’s declaration that life should be lived “intensely,” in pursuit of the experience of beauty. The avatar, or perhaps poster-boy, of the Aesthetic movement was, of course, Oscar Wilde, and it is generally held to have died at his trial.

But the Aesthetic movement—it’s not dead! I observe in the shrill and shaken tones of a horror movie heroine.

The pure experience of beauty became only purer and more beautiful with the advent of abstract painting, and Duchamp was quite right to say that most modern painting presented the identical retinal pleasure grounds in which the eye had been pasturing since Courbet. The Aesthetic movement, and in a sense the nineteenth century, never ended.

I myself made costly proof of this when I acquired a high-grade Mondrian print for my bedroom. I loved that Mondrian. As the phrase goes, “it spoke to me.”

Then came the night when I heard that insistent whisper so familiar from haunted house movies, the one that tells the young family that has has just moved into the surprisingly bargain-priced Victorian house to “get out!“

“That quilt,” the voice admonished. “Lose the quilt!” At dawn I saw that the voice had a point. The Amish item on the bed, for all its geometric understatement , was, next to the Mondrian, a little too rustic. “Oh Piet!” I thought, “Let me live up to you!” I replaced the quilt with something tasteful and monochrome.

In succeeding weeks I lived the beleaguered existence of a character in the Book of Job, which I will quote in the original 1611 King James orthography—as an aesthete, “born to be Wilde,” I can do no less.

Nowe a thing was secretly brought to me, and mine eare receiued a litle thereof. In thoughts from the visions of the night, when deepe sleepe falleth on men: Feare came vpon me, and trembling, which made all my bones to shake. Then a spirit passed before my face: the haire of my flesh stood vp. It stood still, but I could not discerne the forme thereof: an image was before mine eyes, there was silence, and I heard a voyce, saying . . .

“The chair. Lose the chair!”

“Lamp. Don’t like the lamp.”

The room was slowly stripped. Then it was my turn.

“That shirt. Don’t wear it in here!”

I was finally reduced to lying on a futon clad only in a hospital gown, under the baleful glare of the Mondrian’s commanding red square. Then came the moment I knew could not be forever deferred.

“GET OUT!”

There is some art so uncompromising in its loveliness that you can’t live three days unmolested in its presence. There is only one room in a private dwelling where this tyranny of Beauty finds its proper place.

The Guest Room.