The Sphinx was first printed in 1894 in a limited edition, one year before Wilde’s trial. Wilde was then a celebrity, at the height of his arrogance and impudence, and publishing The Sphinx, a poetic catalogue of the erotic misdeeds of Middle Eastern deities, was an act of gay pride and defiance.

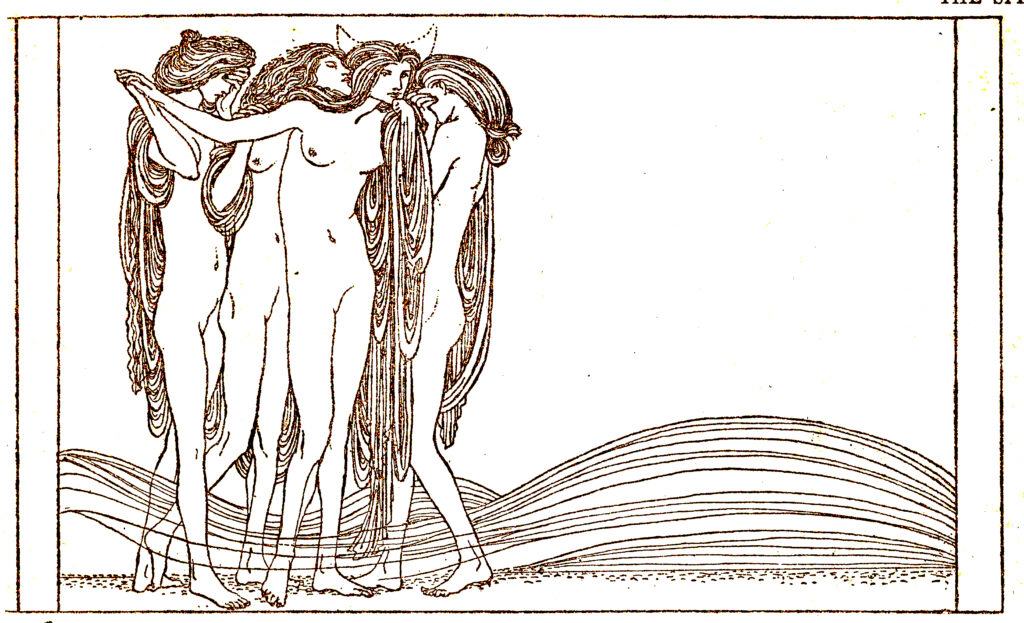

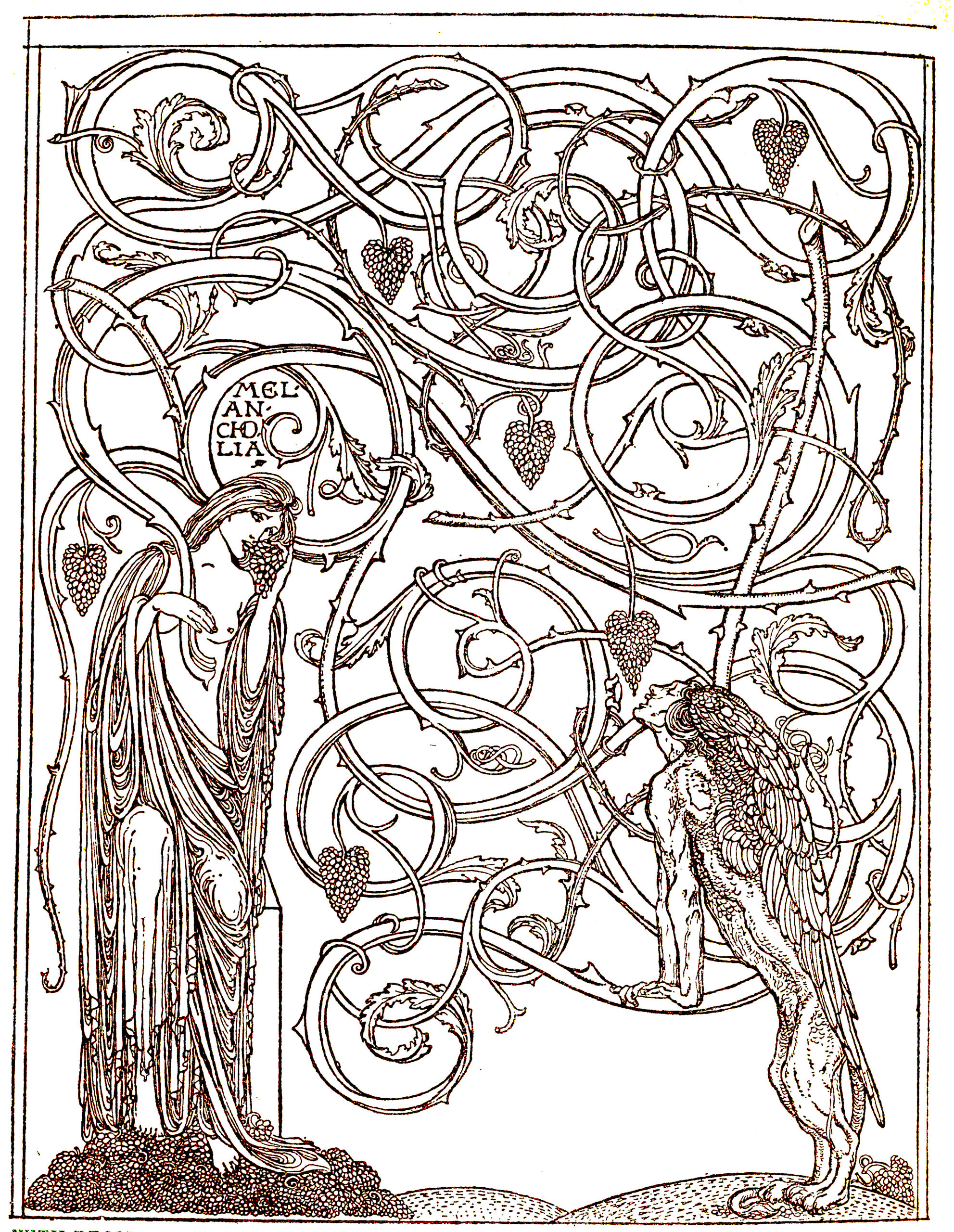

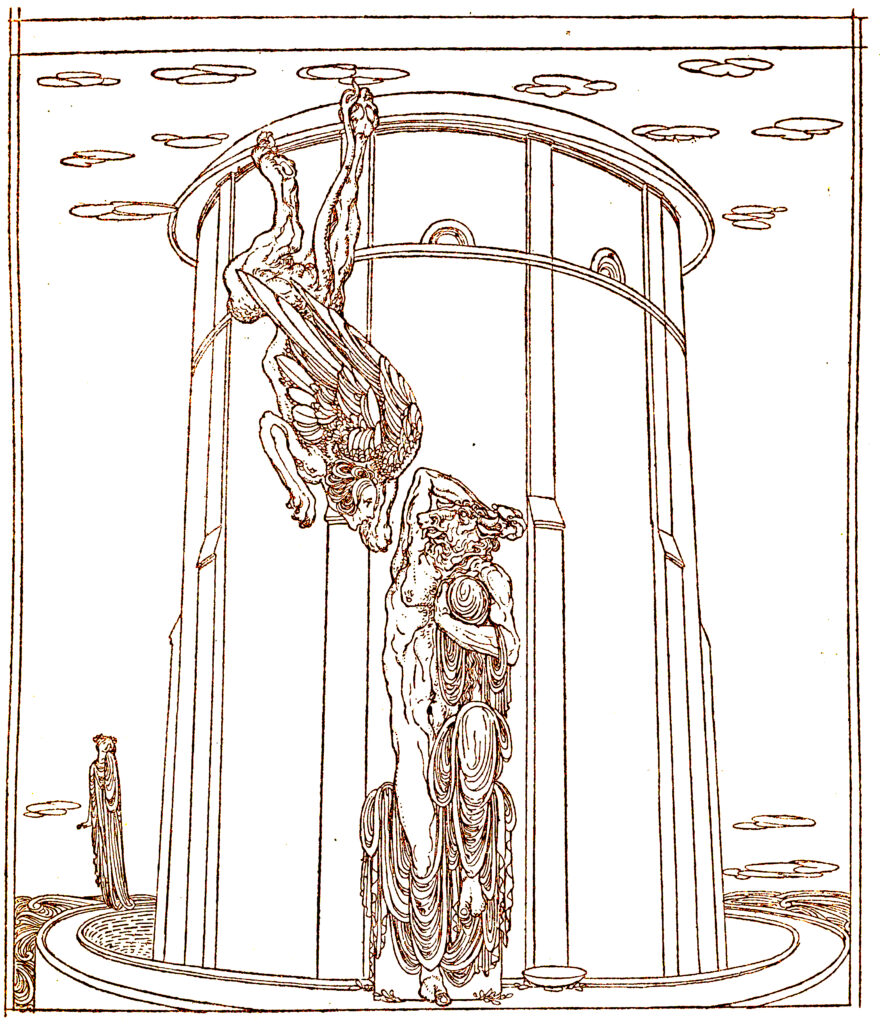

The Sphinx was illustrated by the gay artist Charles Ricketts, who is now best remembered for his theatrical designs (especially those for Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado). For The Sphinx, he not only illustrated, but deepened the meaning of the poem.

Estimates of the poem’s merit generally march with estimates of Decadence and Symbolism. Like a Wagner opera, The Sphinx is simultaneously great and awful; ravishing beauty occasionally interpolated with laughable kitsch. It is a work of flawed magnificence, but it is fun—a merit unshared by many of its betters.

The poem’s greatest claim to our attention is its veiled but unmistakable account of Wilde’s homosexual feelings. He began it when he was a student at Oxford, and worked on it intermittently for the next eleven years. Clearly, it was a poem that meant a great deal to him,

In Wilde’s usage, the sphinx is a figure of sexual ambiguity, a feline and feral symbol of Gay sex, like we find in the famous passage from De Profundis,

People thought it dreadful of me to have entertained at dinner the evil things of life, and to have found pleasure in their company. But then, from the point of view through which I, as an artist in life, approach them, they were delightfully suggestive and stimulating. It was like feasting with panthers; the danger was half the excitement. I used to feel as a snake-charmer must feel when he lures the cobra to stir from the painted cloth or reed basket that holds it and makes it spread its hood at his bidding and sway to and fro in the air as a plant sways restfully in a stream. They were to me the brightest of gilded snakes, their poison was part of their perfection.

Understanding the sphinx as a metaphor for a male love object, we can appreciated why Wilde went to such lengths to camouflage it in a menagerie of mythical sexual images. Some of these expressed him, while most concealed him in a cloud of general erotic connoisseurship. But the truth emerges in the poem’s final sexual ecstasy, which depicts the sphinx mating with a lion and a tiger—pure “feasting with panthers.”

The Bacchic vines suggest a decadent ambiance of excess.

The poem opens with arrival of the Sphinx in Wilde’s student rooms at Oxford, a description that will delight all cat lovers,

In a dim corner of my room

for longer than my fancy thinks

a beautiful and silent sphinx

has watched me through the shifting gloom.

Inviolate and immobile,

she does not rise, she does not stir,

For silver moons are naught to her

and naught to her the suns that reel.

Red follows grey across the air,

the waves of moonlight ebb and flow,

but with the dawn she does not go

and in the night-time she is there.

Dawn follows dawn and nights grow old

and all the while this curious cat

lies couching on the Chinese mat

with eyes of satin rimmed with gold,

Upon the mat she lies and leers

and on the tawny throat of her

flutters the soft and silky fur

or ripples to her pointed ears.

Come forth my lovely seneschal!

so somnolent, so statuesque!

Come forth you exquisite grotesque,

half woman and half animal!

Come forth my lovely languorous sphinx

and put your head upon my knee!

and let me stroke your throat and see

your body spotted like the lynx !

And let me touch those curving claws

of yellow ivory and grasp

the tail that like a monstrous asp

coils round your heavy velvet paws!

A thousand weary centuries

are thine, while I have hardly seen

some twenty summers cast their green

for autumn’s gaudy liveries.

But you can read the hieroglyphs

on the great sandstone obelisks,

and you have talked with basilisks,

and you have looked on hippogriffs.

Lift up your large black satin eyes

which are like cushions where one sinks;

fawn at my feet, fantastic sphinx,

and sing me all your memories!

Wilde relates the Sphinx’s amorous involvements, a catalogue of perverse delights, ranging from necrophilia to bestiality. Many of the most interesting, and virtually all of the homosexual passages, depend on classical and literary allusions which are fully annotated in the printed book, but which are not easily formatted in an online article. (The following relatively straightforward passage receives eleven footnotes in the annotated edition).

Who were your lovers? who were they

who wrestled for you in the dust?

Which was the vessel of your lust,

What leman had you, every day?

Did giant lizards come and crouch

before you on the reedy banks?

Did gryphons with great metal flanks

leap on you in your trampled couch ?

Did monstrous hippopotami

come sidling toward you in the mist?

Did gilt-scaled dragons writhe and twist

with passion as you passed them by?

How subtle-secret is your smile!

Did you love none then? Nay, I know

great Ammon was your bedfellow,

he lay with you beside the Nile!

The river-horses in the slime

trumpeted when they saw him come

odorous with Syrian galbanum

and smeared with spikenard and with thyme.

He came along the river-bank

like some tall galley argent-sailed,

he strode across the waters, mailed

in beauty, and the waters sank.

He strode across the desert sand,

he reached the valley where you lay,

he waited till the dawn of day

then touched your black breasts with his hand.

You kissed his mouth with mouths of flame,

you made the hornèd god your own,

You stood behind him on his throne,

you called him by his secret name.

You whispered monstrous oracles

into the caverns of his ears,

With blood of goats and blood of steers

you taught him monstrous miracles.

White Ammon was your bedfellow!

Your chamber was the steaming Nile,

and with your curved archaic smile

you watched his passion come and go.

The poem ends with an elegy for the lost pagan world of antiquity, which Wilde has brought to life again in the three hundred and forty eight lines of this magnificently weird poem—an opulently illustrated masterpiece of erotica and fantasy literature.

[96th of October’s new edition of Wilde’s The Sphinx, the first to be printed in more than a century containing all ten of Charles Ricketts’ original illustrations, and only one which is fully annotated,may be found on Amazon through this link.]