96 Before we begin I must avow my ignorance on a key point. How do you pronounce Tcherepnin? Where is the accent?

DW The proper Russian accent is on the last syllable, but I’ve heard it pronounced every possible way. I myself tend to alternate. There are also several different way to spell his name in English.

96 Before we get into your recording, Nikolai Tcherepnin, Piano Music, could you give us an overview of Tcherepnin’s place in the history of Russian music?

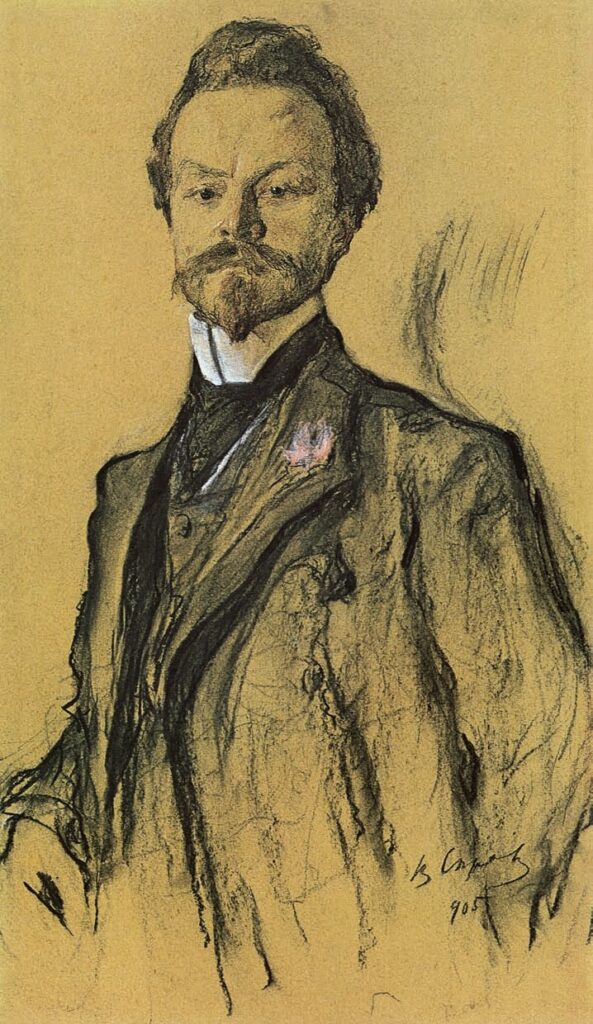

DW He was born in 1873, and he was only six weeks younger than Rachmaninoff. He was a member of the generation following that of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov—who in fact became one of Tcherepin’s composition teachers.

Nikolai Tcherepin grew up in Saint Petersburg. His father encouraged him to become a lawyer. He did go to law school, but studied music seriously at the same time, at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. He finally abandoned law and enrolled in the Conservatory full-time.

His earliest musical style was late Romantic. The first three cuts on my recording, are Tcherepnin’s opus 24, which can be dated approximately to the 1890’s, when he was in his late teens or early twenties. The music could be mistaken for Rachmaninoff or even Scriabin. Then in his late twenties his style evolves in the direction of French Impressionism—his friends gave him the teasing nickname “Debussy Ravelovich.”

The second piece on the CD, the 1908 Pictures from the Russian Alphabet, has a nice mixture and alternation of French Impressionistic and Russian characteristics.

DW As for Tcherepnin’s place in the bigger picture of Russian music, we have to understand historical as well as musical influences.

Russia is unusual in western musical history because it doesn’t have a Baroque or a Classical period. Glinka [1804-1857] was the first important Russian composer, and his work takes shape already well into the nineteenth century.

Nikolai Tcherepnin had kind of a three pronged career. He was a composer, a conductor, a professor—early on he had been quite an accomplished pianist. When he was at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, he mainly taught conducting, not composition. His star pupil was Prokofiev. When Profokiev wrote his graduation piece, the first piano concerto, the other professors were very opposed to its new, harsh style, and Tcherepnin was one of the few who championed Prokofiev.

96 Would it be fair to call Tcherepnin’s style Symbolist? He clearly evolved beyond late Romantic, but he isn’t quite an early modern, like Prokofiev or Stravinsky. Tcherepnin’s music seems to me to have a very magical dreamlike quality.

In Russian history, this was the era of Tsar Alexander III [1845-1894], which saw alongside the grim realist humor of Chekhov and the dialectical materialism of Plekhanov, the mystic current that produced Solov’ev, Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and (to cite some names people have heard of) Rasputin and Blavatsky. Symbolism as a cultural movement represented that kind of rogue fin de siècle spirituality, and Tcherepnin’s music seems to be in that strain.

DW I can make that connection in regard to the Symbolist poet Konstantin Balmont [1867-1942]. Balmont isn’t exclusively famous for his Symbolist poems, but he was so prolific he included Symbolism. He and Tcherepnin became friends when they were living near one another in Paris. On my second Tcherepnin recording, twenty-one out of the twenty-nine songs are settings for Balmont’s poems. But the range of Balmont’s poetry, just on this CD, goes from short fairy tales for very young children, to eighth and ninth century Japanese poetry. He went to Japan and learned the language well enough to make his own translations. Then there are poems that are mystical incantations, his Oceanic Suite, which are inspired by ethnographic research. Tcherepnin used completely different musical styles for each of these poetic modes. In fact, in some of the incantatory songs, he uses a more brutal, ironic modern style. So he could do that to, if he wanted to.

96 Allow me one more attempt to see Tcherepnin as a Symbolist. One of the identifying characteristics of Symbolist art is that it’s very literary in its subject matter. People who don’t much care for Symbolism sometimes say that it’s more illustration than fine art.

Now the selections on your CD, the Alphabet pictures, and the musical interpretations of Pushkin’s fairy tale about the magic fish, could both be called literary—they are musical narratives, what is technically called “program music.”

DW Yes. I would say that from his late twenties on, all of Tcherepnin’s music is either programmatic or linked to literary or artistic works. He also wrote a few operas, so his music is involved with stories or pictures. It’s difficult to find works by Tcherepnin that aren’t programmatic after that initial high-romantic period.

96 If we understand Tcherepnin as a Symbolist, or perhaps less tendentiously, as a literary composer, we can appreciate why he was so drawn to ballet.

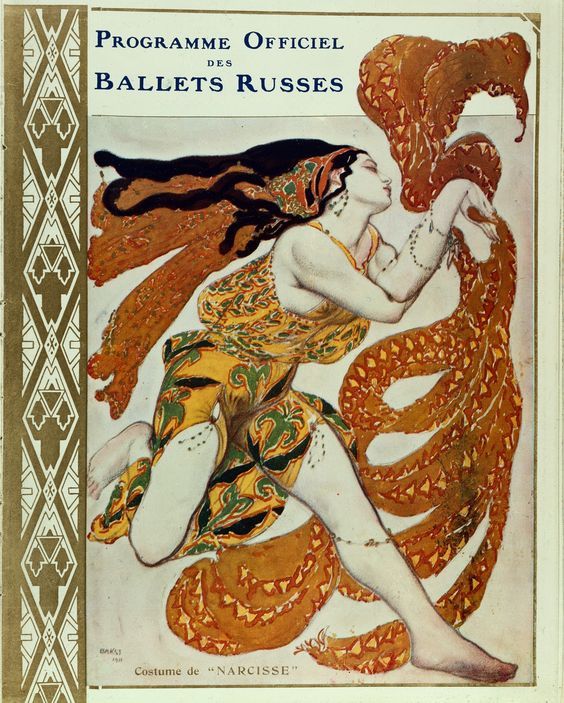

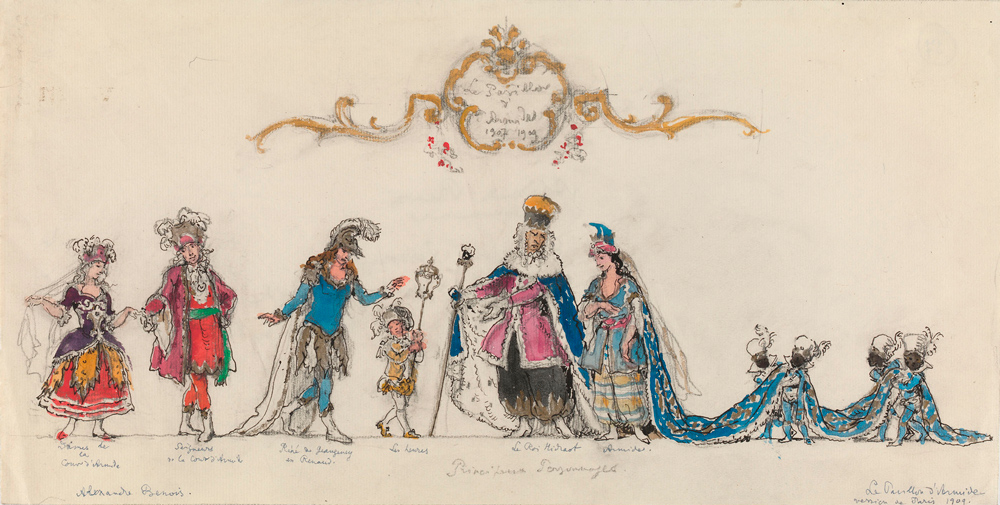

costume design by Leon Bakst

DW In fact it was his first two ballets Le Pavillon d’Armide and Narcisse that really put him on the map musically.

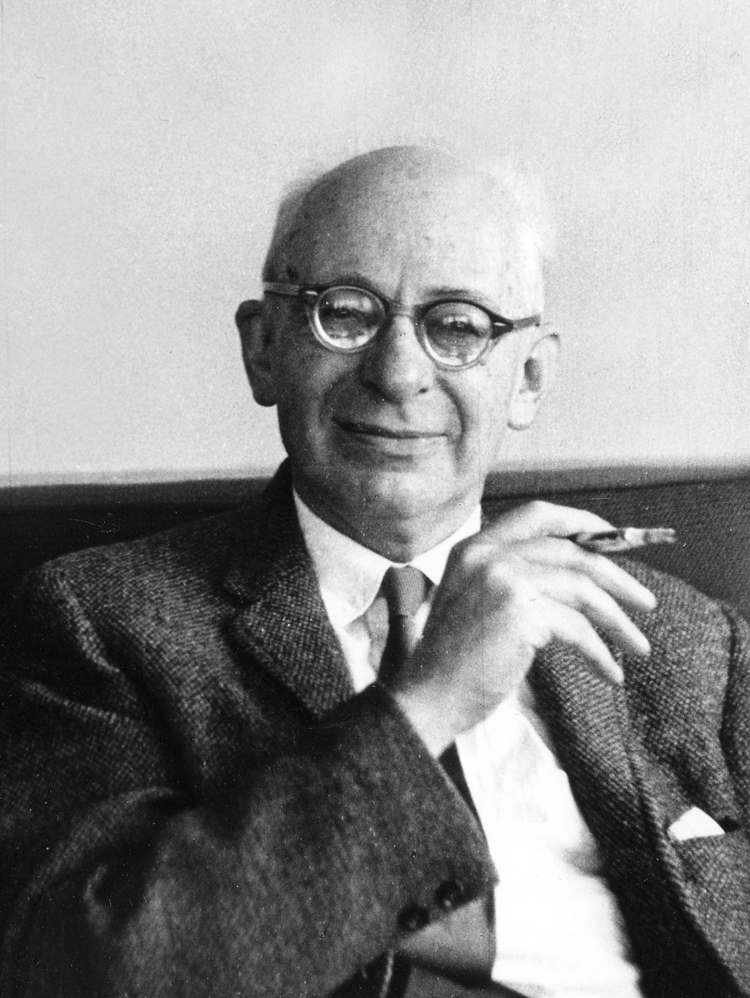

96 After your two Tcherepnin CDs, you went on to record two of the music of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. This composer, who came to America as a refugee during WW II, made a living writing music for Hollywood films. You seem to be consistently drawn to musicians whose work is dramatic and literary.

DW I think that’s correct. But I’m also very drawn to Chopin, whom everyone loves, and with good reason. And his music is decidedly not programmatic.

But Castelnuovo-Tedesco is such an interesting composer. He and his family fled the Nazis and Mussolini in mid-life, and managed to get to America. Because he was a facile composer, could create quickly, after one year in New York, his friends got him a job with MGM in Hollywood, and he began writing music for films. Many of them are not credited to him—scholars have discovered he wrote music for more than two hundred films between 1939 and his death. He also became a teacher for other film composers: Andre Previn, Henry Mancini, John Williams—all the major film composers of the next generation.

96 How did you first become interested in Tcherepnin?

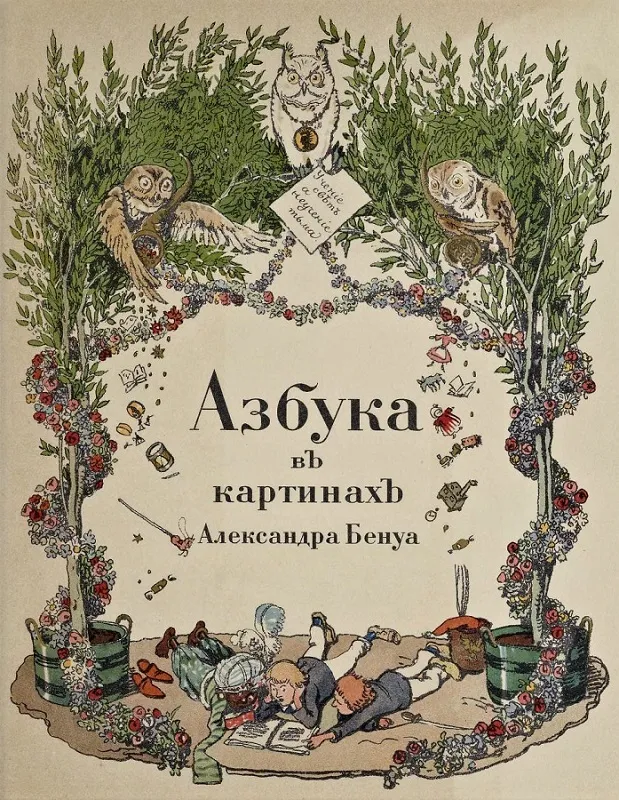

DW It’s really due to my close friend, the flutist Sue-Ellen Hershman, who lives in Boston, where I was in the 1990’s. She got to know Ivan Tcherepnin, the grandson of Nikolai. Ivan was a wonderful composer, and a teacher at Harvard University. Sue-Ellen eventually married him. Unfortunately, Ivan died in 1998; he was only in his mid-fifties. One day when I was visiting Sue-Ellen, after her husband’s passing, she took me out to her garage where they had boxes full of music, quite disorganized—mostly music written by members of Ivan’s family. Not just music by Ivan, but by his father Alexander and his grandfather Nikolai. Sue-Ellen said I could take whatever I wanted, and what looked most interesting to me was something with a very mysterious title, “Fourteen Sketches on Pictures from the Russian Alphabet.” I was intrigued—I had no idea of what they were. When I got home I read the pieces—they were very charming and quite varied. After some research—this was still in the early days of Google—I found its origin a book by the wonderful painter, illustrator and set designer Alexander Benois, The Picture Alphabet.

96 It’s a marvel of book illustration, and very witty. Especially in the tiny figures at in the margins you can see what a delicate sense of humor he had.

[Witten’s CD contains a pamphlet with color reproductions of all of the alphabet images, with Tcherepnin’s own notes in italic and Witten’s comment in roman letters. We reproduce these for three of the pictures here. Click on the titles to access the YouTube recording of the music.]

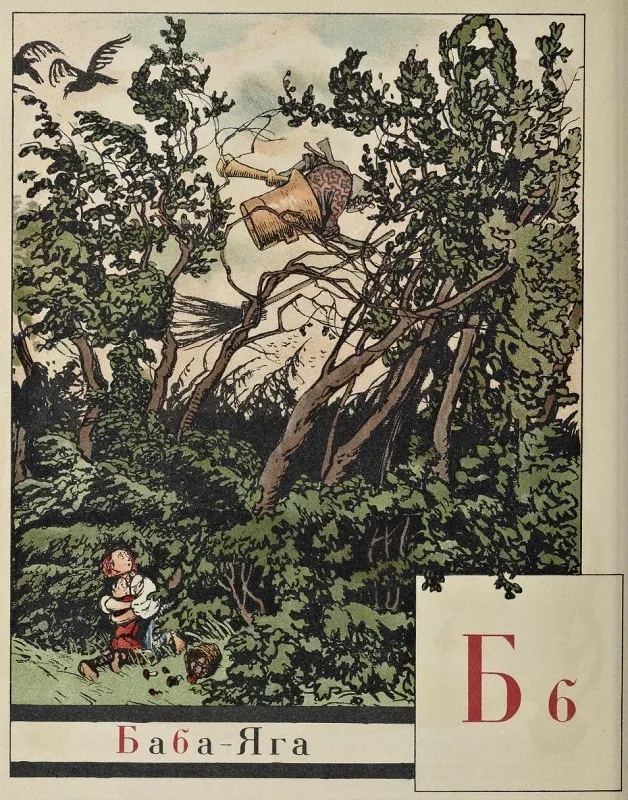

An evil sorceress flies through the air in a mortar.

Lyadov’s devilish 1905 tone-poem of the same name was undoubtedly an inspiration for this music. The galloping rhythms and chromatic screeches of the flying witch are mean to frighten the children.

Learned men in wigs explain the movement of the stars to the nobles.

This stately piece includes dignified staccato-note ‘stars’ rising upward in a zig-zag pattern. It is worth nothing that this music preceded the film score of Star Wars by nearly 70 years.

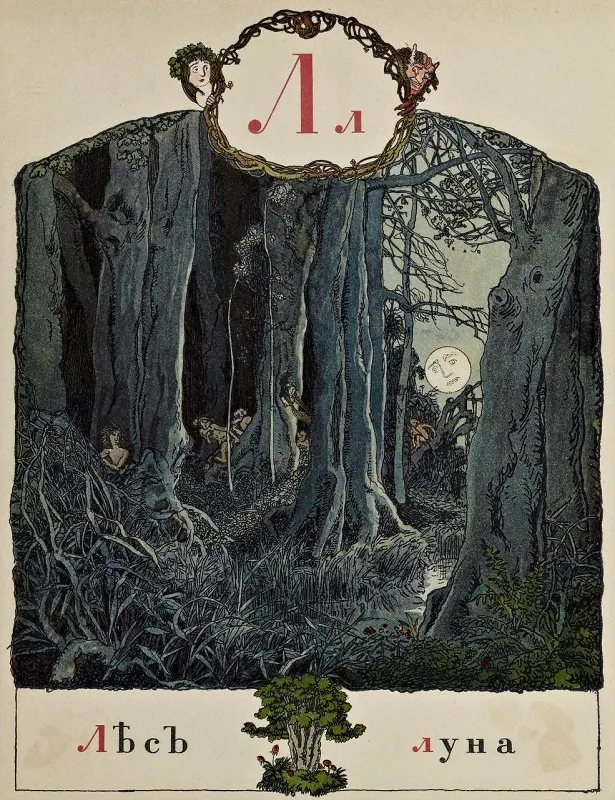

Under the moonlight. Fauns. Dryads and Nymphs.

This atmospheric work is sensual and ethereal, sharing a soundscape with some of Ravel’s compositions, such as Une barque sur l’océan. Legend has it that dryads (tree nymphs) attach themselves to individual trees. When a particular tree dies, its dryad also dies.

96 I believe Benois also designed sets and costumes for the Ballets Russe?

DW That leads us to three great serendipities or coincidences that helped Tcherepnin’s career when he was in his early twenties, which would be 1895-97. He was living in Saint Petersburg, and he was a regular guest at the home of Albert Benois, Alexander’s brother. [Tcherepnin’s Alphabet Sketches came about a decade later, in 1908.]

Albert Benois was a watercolorist, and he would have Friday evening salons which were known as “Watercolor Fridays.” There was wonderful food, musicians would be playing. It was at one of these that Tcherepnin made his debut as a conductor, conducting Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings in as a surprise birthday performance for Albert Benois. This began Tcherepnin’s career as a conductor.

It was at Albert’s home that Tcherepnin met Alexander, who was doing costume and set design for Diaghilev. Diaghilev wasn’t that famous yet, but in he would found the Ballets Russes, for which Tcherepnin would conduct, and which commissioned some of his ballets. Tcherepnin’s first ballet was Le Pavillion d’Armide, with sets and costumes by Alexander Benois.

This was a ghost story—a friendly ghost story, not a scary one. Someone falls asleep and dreams that persons in a painting come to life, and they fall in love and so forth. When Diaghilev saw that ballet, he decided to include it in the first season of the Ballets Russes in Paris in 1909. Actually, the Ballets Russes never performed in Russia, believe it or not. Diaghilev had created so much bad blood with the major theaters that he couldn’t give performances in Russia, so Paris became his base.

It was at one of the Watercolor Fridays that that Nikolai met and fell in love with Albert Benois’ daughter Marie, whom he married, and so began the Tcherepnin musical dynasty, which lasted for four generations. So these were amazing, fateful Friday nights.

It’s worth mentioning that there was a third Benois brother, Leon, an architect, who was the grandfather of the actor Peter Ustinov.

96 Didn’t Tcherepnin almost write the music for the ballet The Firebird?

DW In 1909 Tcherepnin was already the resident conductor for the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev had decided the next season had to feature something with a Russian theme to capitalize on the Parisian interest in all things Russian which the Ballets Russes had created. Diaghilev and his collaborators didn’t choose just one folk tale to make The Firebird, they synthesized elements from several. Everyone assumed that since Tcherepnin was the main musician in this small group, he would write the music. He began to, then stopped. It remains unclear exactly why. It is speculated that he didn’t get along with the choreographer Michel Fokine, who was very strict and demanding. So Diaghilev was looking for another composer. He offered the job to the eminent composer, conductor and performer Anatoly Lyadov, who was a very slow and lazy man. After three months Lyadov, it turned out, hadn’t even bought the manuscript paper to begin writing on. The story goes—and it seems reliable because its source is Alexander Tcherepnin, Nikolai’s son—Nikolai himself suggested, “Why don’t you ask young Igor [Stravinsky]? He’s very talented.”

Stravinsky, who was very young, very brilliant, and hungrier than anyone, came up with a score in a matter of weeks, and that’s the one that became The Firebird.

Nikolai took the music he had written for the ballet and turned it into a tone-poem called The Enchanted Kingdom, which was performed as an orchestral piece three months before The Firebird.

The Firebird was first performed in June 1910, danced by the prima ballerina Tamara Karsavina, and Michel Fokine, the very fussy dancer-choreographer. The lead had first been offered to Anna Pavlova [who created the role of the phenomenally successful The Dying Swan in 1905]. Pavlova was the big star of Russian ballet at the time. When she heard Stravinsky’s score, she said she’d “never dance to that ugly nonsense.” It’s like Steve McQueen turning down the role of Sundance in the movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. A historically big blunder for Pavlova.

96 New Jersey’s Montclair State University, where you teach, is famous for its Peak Performance Series, which hosts performers of the same caliber one would find at the Brooklyn Academy. The music program there is renowned.

DW I’d like to mention that beginning this year Montclair’s Cali School of Music has something called “Immersive Residencies,” which are week long, and gives students the opportunity to study with guest artists like the Kronos Quartet, the Harlem Quartet, the jazz musician Wynton Marsalis, and the percussionist Evelyn Glennie.

96 How did you end up at Montclair State?

DW I finished my doctorate in music, in piano performance, at Boston University. Of course I loved living in Boston and Cambridge, but I wanted a full-time job. I searched for years, then in 1997, I had not one but two job offers. Count ‘em, one two, buckle my shoe, two! One was at SUNY Potsdam [near the border with Canada], the other was Montclair State University. Montclair seemed much more attractive, being near New York, so I took this full-time job. I liked Boston, but I had twenty different part-time jobs, and I was running around for as a freelancer, always concerned to keep my car in good shape. So I took this on, single full-time job, and I’ve been here for twenty-five years now.

96 What are you working on now?

DW I have a new CD called Three Generations, which features chamber music by Nikolai, Alexander and Ivan Tcherepnin.

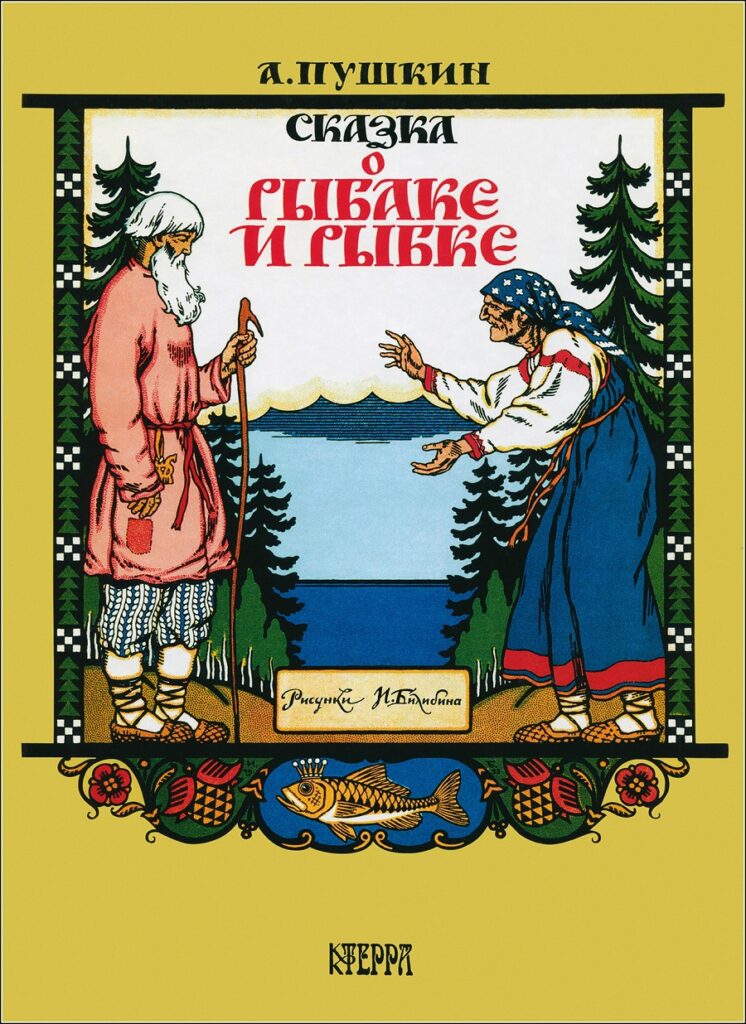

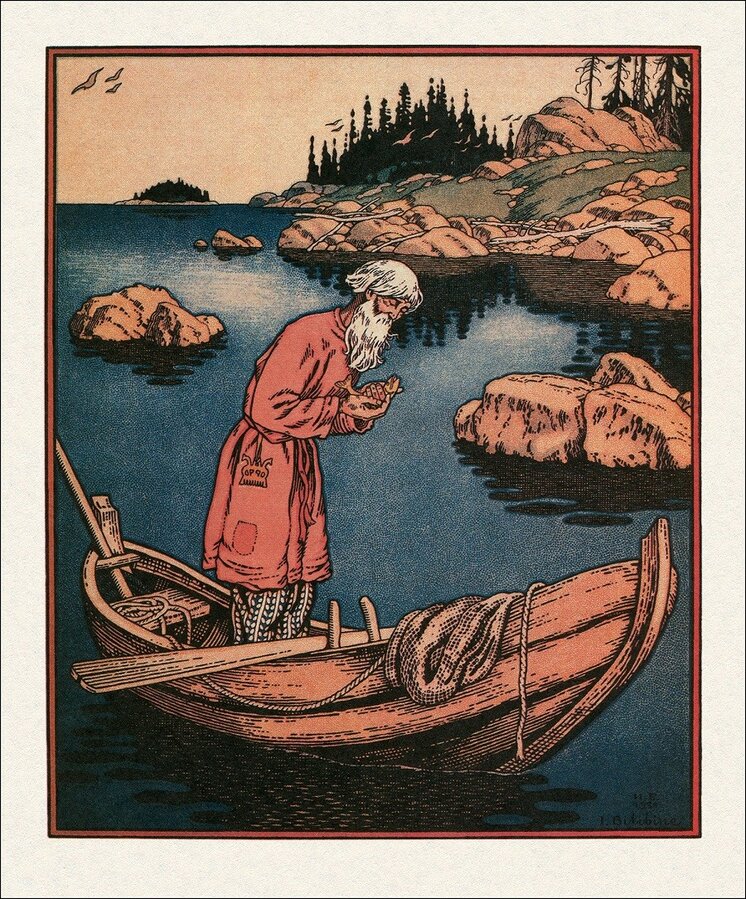

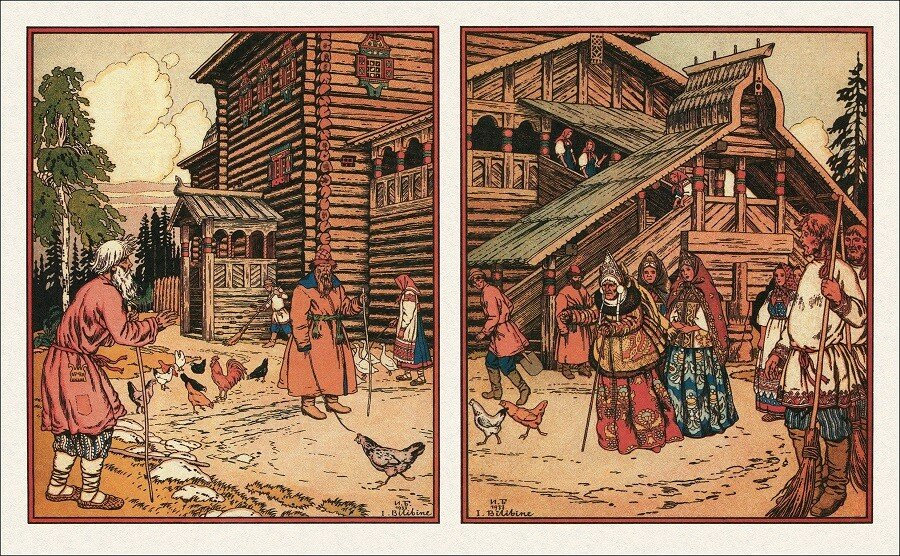

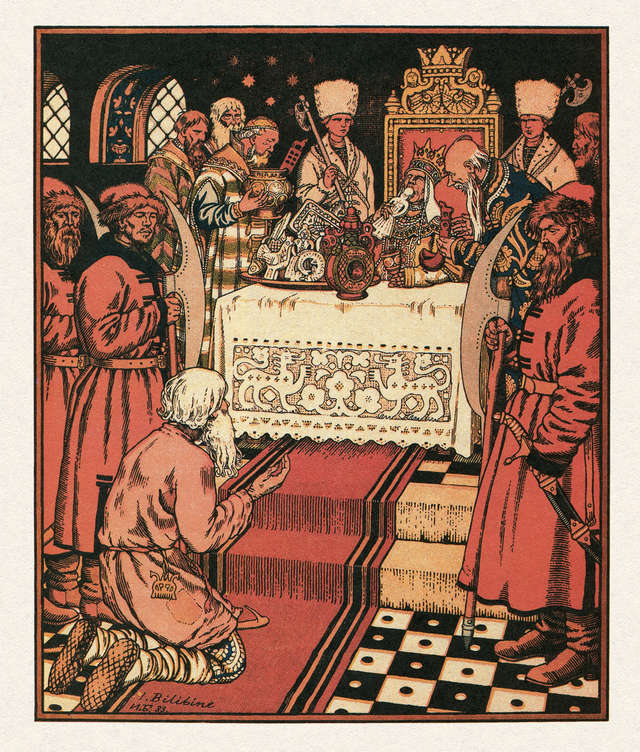

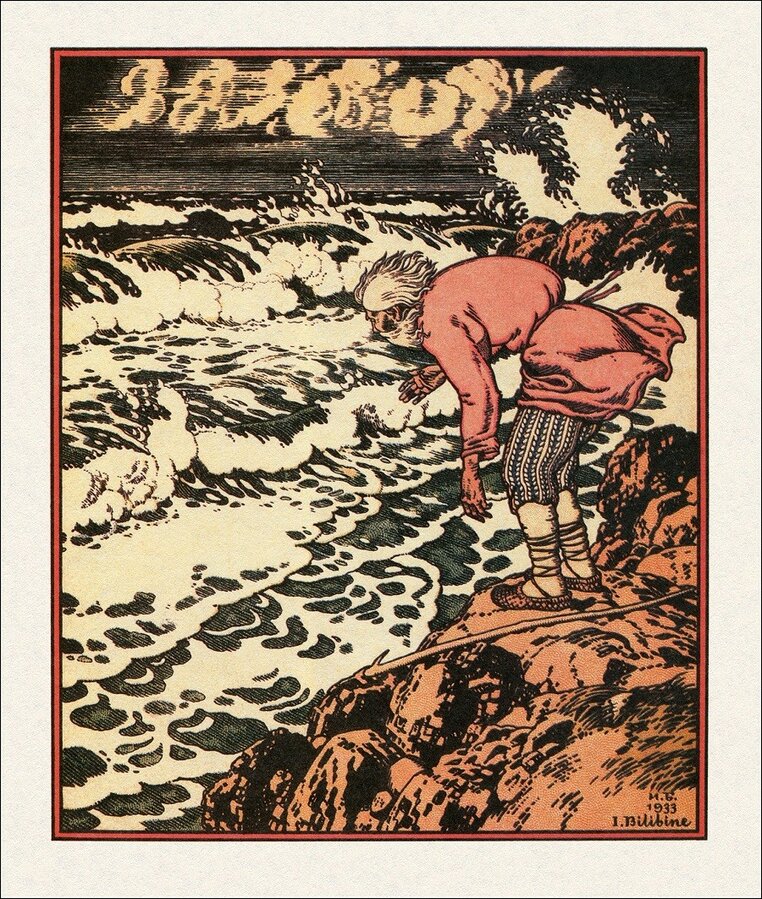

David Witten’s CD of Tcherepnin’s piano music concludes with The Fisherman and the Fish, based on a Russian Fairy Tale retold in verse by Pushkin. The music was designed interpret the poem as it was read aloud, episode by episode. The pamphlet in the CD gives the full text of the poem.

Bilibin made his illustrations in the early 1930’s, and Tcherepnin finished this composition by 1915, so if there was any influence it was of the music on the illustrations. But these magical graphics wonderfully match the mood of Tcherepnin’s musical fantasy.

According to the story, an abjectly poor fisherman catches a golden fish,

which asks him to be set free, offering to grant a wish in return. The good old man releases the creature without making any deman, out of the goodness of his heart.

When he returns home, his shrewish wife berates him, and sends him back to ask that their hut be replaced with a fine house.

On his return, the wish is granted, but the wife is not content with this. Go back and ask for a palace!

The poor man returns to find his wife a Tsaritsa, who treats him with regal scorn.

This cut from Witten’s CD describes the imperious majesty of the sovereign spouse.

This is of course not the end of her demands, now she wants to be Empress of the Ocean and make the golden fish her slave.

The long-suffering fisherman makes this request as well, which results in the forfeiture of all the fish’s gifts. The palace is once more a wretched hut, and we learn a good moral lesson about contentment with what one has, as well as gaining some insights into archaic Russian expectations regarding women, and the special place of the underwater world in a country exceptionally rich in rivers, for which access to the sea was always the key to wealth.

David Witten will be co-directing the the Taubman Piano Festival at Montclair State, June 24-26. Click for more information.