Chapter 9

Istehar Sha’an, Illuminatrix

Silvirium, Undersong House

Ancilliday, 9:30 a.m.

When we fled, we took the air in our lungs. We took herbs, roots, and flowers in our medicine boxes. We took staffs and bows made from branches gifted us by wind and rain. We took cups and bowls carved from burls. We took children on our backs, with wilted wreaths on their heads and seeds in their pockets. In a sack, I carried our Books of the Tree. The forest came with us; it shelters us still. But this city will never understand that.

I will never forget the first time a Librarian opened a Book of the Tree to see what was in it. It was not long after our miserable arrival, when we were all penned at a checkpoint in the Vexriver Fortress south of the city. Such a shiver passed through the man when he opened the cover of rough, ridged, and furrowed bark, and saw the thousand carefully handmade pages were blank. He turned page after page but could make out no writing, no language at all. I think the city’s hatred of the Sha’an was born in that moment.

“If you produce books like this, you’ll be begging on the streets in no time,” he said.

“Books like this are how we survived this long,” I told him.

Morning prayers are finished. I have sent everyone out of the silvirium, even my friend Tiarath with whom I often sit after prayers, and closed the door. Surrounded by potted trees and sunlight pouring through glass walls, I open the Book of the Tree that lies on a moss-silk pillow, the heavy one with a cover of thickly furrowed bark and yellowed pages, the one my teacher’s teachers made, that has held our memories for generations. A young apple tree, planted in a hole in the floor, pokes its branches up through apertures in the ceiling, its foaming blossoms and pale green leaves sheltering me and the book. Other Books of the Tree, even older, with pages fraying at the edges, hum to themselves in an ark in the corner. Once we prayed in a towering grove; now we must fit into this little room.

I speak to my ancestors, human and arboreal. I ask how to protect my little tribe in this vast heartless city. There is no ill archprince now for us to cure. And where can we go if we leave here? The Sha’an forests are smoke now, and evil folk rule the treeless fields that are left.

I press my hand to a page and close my eyes. Forest floor rises up, fungus and damp soil. A circle of houses half-buried in the earth. My parents, alive. I climb down a ladder into a deep roofed pit. Zilfa, the illuminatrix who came before me, takes my index finger, holds it to the earth, then to a page of the book open before her. She is showing me how to imprint the page with feelings and sensations and memories, how to fill it with the light of the day. In this deep place, webs of roothair poking from the walls, I feel safe, sheltered by trees and earth.

My foolish brain interrupts my vision. Why has the book shown me this moment? We should not have to hide underground. We are allowed to live here. That was what the Council promised us, the day they sent me to the River School. The Moonstone princes wanted me to become one of them, to lead my people like a lady of Moonstone and not like an illuminatrix of the Sha’an. I knew I would never do that, but I went to the school, to buy goodwill for my people. And there I found what I did not expect: a family to replace the one I lost. A family as diverse and raucous as this city. A family I will soon lose, if the Sha’an are driven from this place — or else my wives will have to come into exile with me, and I do not want that for them.

Guided by the all-seeing trees, I feel her before I see her: a fierce beast of a person, raging into the house. She is urgent, intent on her hunting. I hear her steps in the hall. She opens the door into the silvirium, then stops, shame-faced to be barging into a sacred place. I turn to look at her, jolted as the vision of the book and my eyes’ vision align. Annlynn bows a little and makes that funny two-handed Abbatine gesture — pinching the first three fingers on both hands to make saints’ candles. I carefully close the book. The vision fades.

“I might know who killed Loli’s parents,” she says urgently. “But I need your help. I need you to do something very hard.”

“Yes,” I say.

There is, apparently, no time for boats. I leave behind my staff, thinking the Librarians may find it worrisome, but I feel unsteady without it. Annlynn herds me over the little bridge to Inkstone Point, and then through a maze of bridges and alleys, boardwalks and catwalks. I hurry after her as if we

are fleeing for our lives. The damp air is chilly on my skin; I have forgotten my shawl. The great hive hums at the edge of my consciousness, as it always has ever since I came to this city. We pass carts of jewel-like fruit from the micro-orchards of Seven Lanterns, pots of pickled fish being sold at market, ancillas begging for alms for their sisters in the ancillary, and weavers hawking cloaks of sea-sheep wool. All of it makes no sound to me, compared to the Library.

As we cross the Long Bridge onto Opal Island, the buzz of thousands of voices grows louder and louder, like a landslide starting. We wind up arrow slanting streets and under high arches, passing haughty-looking deacons, stern sentinels, schoolchildren, poor folk seeking day labor, and the palanquins of ladies. As we come around a sharp corner, the great white dome appears. The voices in my head are like hornets, stinging me with hopes and fears, with stories, laws, and dreams. As we make our way across Festival Square, I have to stop to get my breath. When Annlynn speaks to me, I cannot hear what she is saying.

The voices of a forest are calming, but the voices of books — the consciousness of trees bonded with human words and will — are far more demanding. I have been in this building only once before, to meet with the archprince and the Council, and I was in bed for days afterward with what felt like an iron stake in my brain. The first time I really spoke with Annlynn, back at the River School, I told her I could not come even so far as the market in Festival Square. She liked that about me. But now she wants me to go into the Library itself.

She rushes me up smooth marble steps guarded by black-clad warriors. As they search our bags, I notice some of these folk looking at one another — what is Annlynn’s snowhaired witch doing here? But Annlynn pays them no attention, and in moments we are in the red, dark halls of this ancient anthill, with little noisy books lining shelves and shelves and shelves as if they will go out as an army and overrun the world.

We go down steps and around corners. People stare as we pass. I clutch my head. “Just a little farther,” urges Annlynn. A friendly face looks out from a doorway and through that doorway we go. There is a cluttered office with cabinets and a table, and on the table are two books I know. One looks like the book I brought to Loli as a birthday present. The other looks like the one I saw on the table when I met with the Council: the Moonstone Covenant. But it is not the same book; I can feel that in the ripples it leaks into the room.

Annlynn solemnly hands me the smaller book: The Poisoner’s Guide. I hold it and try to concentrate, to shut out the myriad books clamoring at me like babies wanting to be fed. Annlynn and Tommas watch me intently and anxiously, as if I may explode.

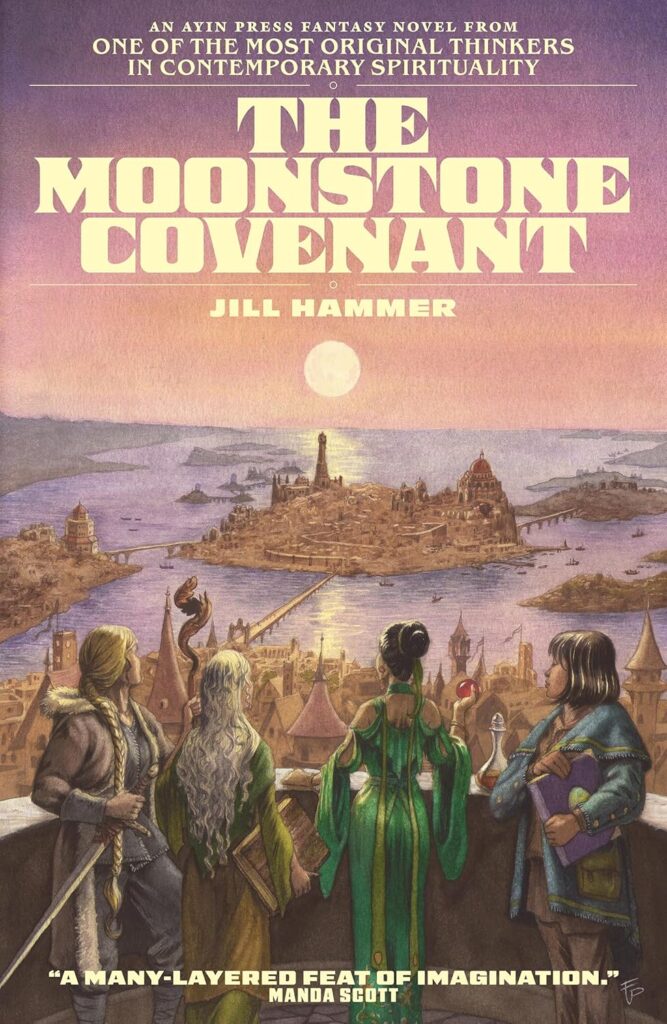

Jill Hammer’s new fantasy novel, The Moonstone Covenant, from which this excerpt was taken, may be purchased here.