A POX ON BOTH OUR HOUSES

Ah, syphilis—so sweet, so soft and sibilant, the most beautiful word in the English language. I sing the infectious tune, the bacterial psalm: Praise Ye the Great Pox, also known as paresis, the lues, button scurvy, frenga, gumma, and (to the Turks) the Christian Disease. All these names ring baleful bells inside my skull, calling forth a heady combination of disgust, derangement, and exaltation.

1.

A madman’s maunderings? Or the secret truth vouchsafed to only the most elect and exalted of adepts, secreted away in the innermost chamber of the mind, the cerebral sanctum sanctorum where graceful white worms, microscopic Loch Ness monsters, raise their eyeless heads, rearing in erectile serpentine coils, writhing up and out of the neural swamp.

Nietzsche went utterly mad, though the spirochetes eating away at his brain didn’t prevent his greatest work from being written. Beethoven lost his hearing to the pox as he ascended into the heavenly musical realms. Donizetti was infected too, when he created his greatest opera: The Elixir of Love. Gaugin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Rimbaud, and Baudelaire were ravaged by the French malady (as the English called it.) Most Top Ten Lists of syphilitics also include Al Capone, Oscar Wilde, Cesare Borgia, and Hitler.

I am convinced that Idi Amin and Christopher Columbus—two paragons of megalomania—were both infected with the pox. On the other hand, only the most insane dare to suggest that Napoleon, Elvis, Captain Ahab, or James Brown were syphilitics, though all were plagued by grandiose delusions. In other words, just because a man is a towering inferno of arrogance doesn’t mean his brain is swarming with spirochetes. Likewise, though there is indeed a link between greatness and having one’s brain melt into a gleaming puddle of slime, not all gibbering madmen are geniuses.

2.

Wandering alone in Mount Hope Cemetery, I came across a large stone bearing an accursed name. Though I’d made pilgrimages to the cemetery dozens of times before, until then I’d never noticed the grave marker.

Or, to be more honest, I had not allowed myself to truly see the name, let alone say it aloud. The name itself is a nullity, a negation of itself and the writer who carried it to late fame and ill fortune. Two simple syllables: the first being “love,” an emotional state he never truly experienced, the second being “craft,” of which as a writer he was entirely devoid. Instead of love, he was most often consumed with loathing; instead of craft, he was swamped under purple prose pulp gibberish.

And so, I discovered that the Sad Syphilitic Seer had ancestral roots deep in the soil of my natal city. His stern fathers (as he called them) lay dreaming ’neath the mould, just a few minute’s walk from where my progenitors are buried. To the best of my knowledge, we have no literal genealogical connection; yet his forebears and mine have dissolved into the same fertile burial earth. Deep below the ground, our ancestral roots are tangled.

Mount Hope—called by one Victorian visitor a “Beautiful City of the Dead”—is a sprawling park cemetery, with charming hillocks and lost dells, hidden ponds, glacial sink-holes, winding trails, collapsing tombs, and delightful necropolitan sculpture. Rotting oblong boxes that hold human remains, stones with names slowly obliterated by the icy winds of time: our ancestors are reduced to this. Yet deep in Mount Hope, there is another unspeakably eldritch force at work.

3.

Though his words have been much misconstrued, Nietzsche famously declared that God is dead. A far lesser writer took that idea and gave it a necro-cosmic spin. Though an arch-atheist, he created a pantheon of monstrous dead-alive deities.

The fiction writer who creates gods is in effect a meta-god, existing on a higher level of reality than his creations. From such a diseased mind came Azathoth, “the blind idiot god” who sprawls in the center of Ultimate Chaos. This cosmic cretin is described as the “Lord of All Things, encircled by his flopping horde of mindless and amorphous dancers, and lulled by the thin monotonous piping of a demonic flute held in nameless paws.” Flopping hordes? Nameless paws? This could be a fever dream populated by drunken hell-Muppets.

Also in this unpronounceable pantheon are Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep, and Shub-Niggurath. But most famous of all these horrific deities is Cthulhu, who lies hidden under the sea for eons, dreaming, waiting for his opportunity to erupt into the light of day. The followers of Cthulhu were known to chant at their obscenely unspeakable rites this gibberish prayer: “Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn,” which supposedly means, “In his house at R’lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming.”

Like so many monsters, Cthulhu is a slimy, reeking, vaguely anthropoid mix-and-match mess. Its head is like an octopus, with a face comprising a mass of feelers. There are also vestigial wings and claws on hind and fore feet.

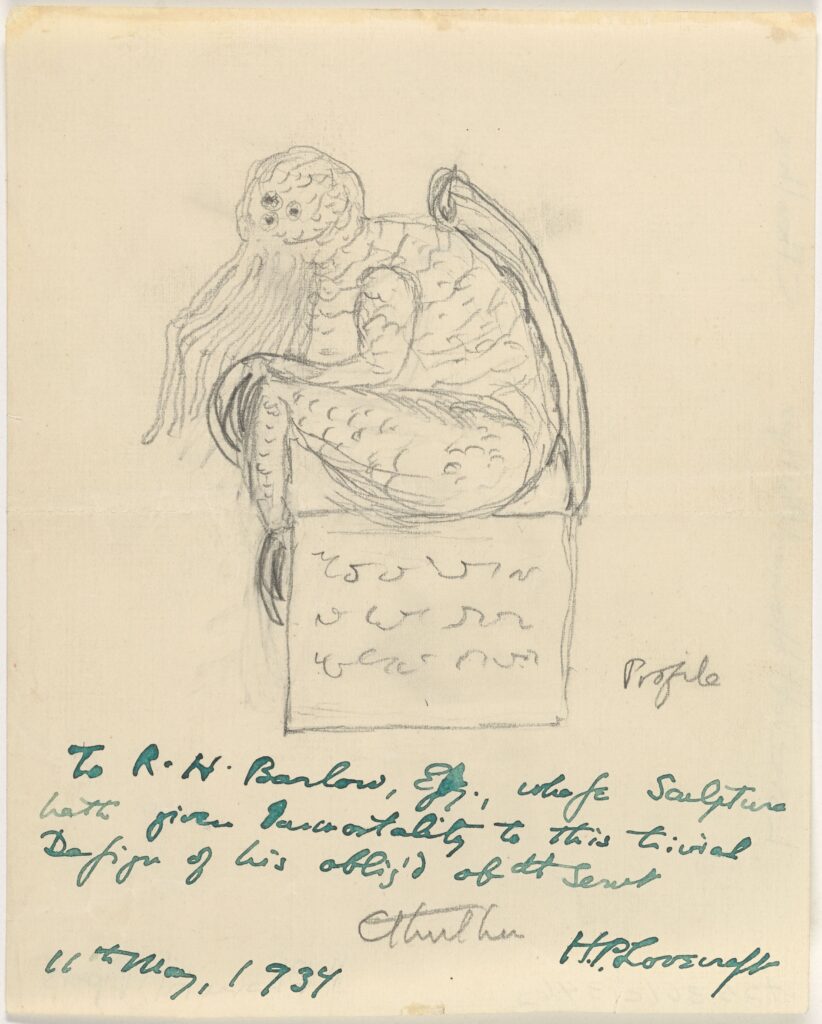

A drawing included in a 1934 letter makes Cthulhu look like an overweight girl sitting on the toilet. The tentacles hang to her knees, like long locks of stringy hair. Her chubby legs are pulled up slightly, and she leans forward on the square potty, not so much horrifying as embarrassed to be seen. Could the writer’s raving fears derive from a glimpse he once got of his mother on the toilet? A self-styled hyper-rationalist, he didn’t just ignore the obvious. He literally could not see it.

In “The Call of Cthulhu,” at the pinnacle (or nadir – depending on one’s point of view) of horror, when the writer has used up all his hyperbolic adjectives, he tells us his secret. “There was a bursting as of an exploding bladder . . . a slushy nastiness . . . a stench.” Perhaps a little boy couldn’t could hold his water any longer, yanked open the bathroom door, and there it was, he was, she was.

The description of Cthulhu might be the perverse fantasy of an autistic middle-aged man who’d never actually seen female genitals: “a pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings.” Was this his twisted notion of the clitoris, labia, and pubic hair magnified a thousand-fold and set loose as an unspeakable sex-monster?

For what are his Cthulhu and such ilk but great vulva-form deities in drag? A quivering rugose cone indeed, leaving behind an odiferous ooze trail that drives men to delirium. These fulgurous and fungoid alien entities are from the stars, yet they lay hidden for eons in the deepest sea, causing literal insanity when they emerge from their slime-washed dens. Cthulhu’s creator especially hated the smell of the ocean at low tide (when secrets are revealed). In the story “Dagon,” the narrator must traverse a stretch of sea-floor that had been mysteriously thrust up to the surface, putrid with the carcasses of decaying fish. This vile and vivid vision of gasping wet gill-slits and grasping tentacles is enough to drive his protagonist into soul-shattering mental chaos. He uses the word “cephalopod” as though it in itself would terrify the reader. Why mollusks (octopus, squid, cuttlefish) were so odious to him is not hard to fathom. If a nice plate of cod or haddock were nauseating, how much more so were soft, slippery, tentacled, odorous sea creatures?

4.

In the final stages of syphilitic dementia, the physical symptoms are easily diagnosed: blurred vision, a wobbling gait, drooping eyelids, deafness. Other signs are more subjective: plaguing sensations of electric current in the head, humming and whistling in the ears, disorientation and violent rages, loss of memory. The last group of symptoms is most puzzling, but highly suggestive: bursts of creative energy, auditory hallucinations (such as being serenaded by angels), euphoria, delusional and grandiose self-definition, messianic prophesies, mystical visions.

Seen from a medical perspective, these describe the last stages of an untreated treponema pallidum infection. Seen from an esoteric point of view, this list points in a far more disturbing direction: syphilis as the cosmic solvent.

Cthulhu’s creator—the Nameless One, my patron saint and nemesis—was haunted by the syphilitic madness that had consumed his father. Spirochetes—shimmering, microscopic, wriggling, translucent threads—were at the heart of his horrors, literary and otherwise. The protagonists in his stories are a feeble and unstable lot. They faint, they quake, they shriek and gibber, go berserk, jab themselves full of morphine, and long for the courage to commit suicide, when the horrid truth is revealed. Like their creator, they have almost no agency in the world. They stumble upon forbidden sexual secrets, go too far in their investigations, and end their lives as raving wrecks.

In places the writer’s loathing overwhelms him, leaking out in stories is so badly wrought they might be a parody of the worst pulpy purplish prose imaginable. But it is in the hyperbolic imbecility of the verbiage that its power lies. Skills and talents—negligible. Craft—zero. Intelligence—there was some, but it was routed into dead-ends and dismal holes. Literary friends—most of these hacks he knew only through the mail. As a writer, a husband, a functional adult, he was an abysmal failure, and he didn’t even have liquor, drugs, or whoring to blame. Adding in his flaming racism, partially-submerged homophobia, and quivering fear of female genitals, the creator Cthulhu was a repulsive wretch.

While his mind disintegrated, he cloaked himself with many guises, and with many names. The trans-plutonian emissary: Eich-Pi-El. The mad Arab: Abdul Al-Hazred. The ancient Egyptian priest: Lu-Vah-Kareph. Consumed by megalomania: “I am Providence.” This phrase, taken from one of his letters, is his epitaph. Swan Point cemetery, in Providence, Rhode Island, holds his mortal remains. But another city, and another cemetery, looms with far more malefic power.

5.

His father was born and raised in Rochester, and he died wracked by syphilitic insanity, locked in a madhouse. Likewise, his cousin Joshua went insane and died of so-called paresis in the same year—1898. Would my nemesis also end his life that way? From early childhood (his father died when he was seven) he feared such a dismal fate.

He hated Rochester, hated and feared the name so deeply that he could not bear to say it aloud. Though blandly Anglo-Saxon, this “Nameless City” evoked all that was most noxious and noisome for him, a one-word magic spell that promised dissolution, degeneration, and madness.

Bland, even vapid, the name Rochester hardly seems to call up images of baleful rites or ancient mysteries. Much better would’ve been the original name of this place: Carthage.

As a teenager, I read far too many books by Robert E. Howard, another Cthuhlu-mythos fictioneer, best known as creator of Conan the Barbarian. One of his earliest stories is called “Delenda Est Carthago” (Carthage must be destroyed.) Though I never studied Latin in school, I carried that phrase for decades. Yes, Carthage must be destroyed, not by Rome, but by Rochester. Bloody battles, grand heroes (Hamilcar Barca and his son, Hannibal), mythic doom and carnage: these specters are raised by the name Carthage. The hamlet here was swallowed up and disappeared, like its ancient north African namesake. And Rochester, a solid Kentish word, became firmly attached to this city.

Digging into old English history, however, I found that the name is imbued with mystery. I knew that chester was an English version of castra (Latin: meaning an armed camp or stronghold). The derivation of many town names ending with chester are obvious—e.g.: Westchester, the camp in the west. But what did Ro mean?

Laboriously paging through some musty tomes, I learned that the original name was Hrofes Caester. (The camp of some mythic ancient Briton named Hrofi.) This, over the centuries, became Hrofescester, Rovescester, and by Shakespeares’s day, Rochester.

The most famous men named Rochester carry a tainted kind of glory. In Jane Eyre, Edward Fairfax Rochester is cursed by love, with an insane wife locked away in the attic. There’s also Eddie Rochester, Jack Benny’s black sidekick. Though subservient, he’s still always one up on his white boss. My favorite Eddie Rochester appearance is in Topper Returns, the third in the series of ghost comedies. Rochester has a prominent role, as a chauffeur who wears an ankle-length fur coat and is one of the few in the film who actually understands the situation. There is indeed a sexy ghost flitting about and Rochester knows that hanging around her is a very bad idea.

At the head of the list though is John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester, the greatest poet of obscenity in the English language, dead at age thirty-three, destroyed by syphilis.

6.

Decades ago, a bootleg tape was passed along surreptitiously to me: a British actor performing the erotic poetry of Lord Rochester. It’s been decades since I listened. Now, at last, I have dug it out of a sagging box full of almost-forgotten treasures: dozens of cassettes going yellow and brittle with age. I listen with headphones, in privacy, in secrecy, in darkness.

The poems have lost none of their scurrilous glamor, brimming with oblique obscenity, ordinary filthy words turned sideways and tricked out in witty rhymes, not quite sneering, not quite sniggering.

The tape no longer tracks properly. The actor fades in and out, as though going below water, drowning and gurgling, then rises to the surface as the tape heads catch squarely and the sound runs true for a few lines. Archaic words and now-archaic technology: faint hissing in the background and the actor’s breathy half-whispered voice, tremulous, then tremendous. He boasts of erotic conquests and he laments lost sexual prowess. He gives forth spurts of blasphemy, palace gossip, elegant bluster, crude insults, and the elaborate bedroom incantations which raise from the dead old whores whose names mean nothing and old kings, absurd, pompous, and negligible.

A witticism of this time – “one night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury” – refers to “the sweats,” a mercurous steam bath which was thought to slow down the pox’s progress. Lord Rochester enjoyed periods of remission; however, there was no medicine to prevent his inevitable slide into symptomatic hell: blood in his urine, fits of blindness, excruciating joint pain, weeping chancres, hectic fevers, hair loss.

As the pox ravaged his body, Lord Rochester’s poetry veered from execration of his enemies to self-loathing, from fury and spite to self-pitying despair. In his words, he was consumed with “anger, spleen, revenge, and shame.”

7.

The Prophet of Providence delighted in travel, especially to inspect old forms of architecture and primeval monuments, and took great pleasure in delving into his genealogy. Yet he made no mention of visiting Rochester, his familial home. Dreading and hating this city, he makes only oblique references to it in his thousands of letters.

That his ancestors and mine sleep in the same Beautiful City of the Dead is crucial to me. There are, however, other significant connections. Our fathers were born in the same city and both of them died—with disease-ravaged brains—far too young. Though both of us were fixated on genealogical secrets, neither of us produced any offspring by the usual biological methods. Though we both authored much fiction, we also spent perhaps too much time writing long and detailed letters to our friends. We were both widely published, yet made only a modicum of money through our literary efforts. Also, for neither of us is the past something to be despised and disdained like an embarrassing idiot relative. Graveyards and the architecture of previous ages have a heady effect. History is not something to be scorned and forgotten, but can be seen, and felt, as a repository of truth and even revelation.

His father’s birthplace, a house on Marshall Street, still stands. It isn’t, as the son would have liked, a fine example of federal or colonial architecture. Nonetheless, it has one feature that captures the viewer’s attention. A squarish tower looms above the third story, giving the house a grand, though unbalanced and minatory, aspect. After discovering the family plot in Mount Hope Cemetery, I made my first pilgrimage to Marshall Street, and stood a long while gazing up at that strangely proportioned tower.

The accursed progenitor worked as a blacksmith at the James Cunningham carriage factory making hearses. He left Rochester in 1874 at the age of twenty-one. His whereabouts for the next fifteen years are unknown, though it was during this period that he contracted the deadly pox. In 1889, he emerged from the haze of obscurity, taking a job with Gorham and Company, silversmiths in Providence. Apparently, he was drawn to metals: a hewer of iron, a seller of silver, and finally dosed with mercury.

In 1893 he suffered a complete mental breakdown while on a business trip in Chicago. Sent back east to a mental institution in Providence, he passed through Rochester on the New York Central trunkline, as his mind dissolved into a puddle of glistening goo. It is possible that he had earlier infected his wife. His breakdown came less than three years after their son was born. It is also possible for a mother to transmit the disease to her baby during pregnancy and birth.

As he passed through Rochester a final time—heading home on the train in late April of 1893—he ranted and railed about a black man performing outrages on his wife. Accompanied back to Providence, he was admitted to Butler Hospital, where he lived out his last five years, a prisoner within the four walls of the asylum, a prisoner of his pox-ridden body and mind.

The Eldritch Author’s fear of madness was made even more severe when his mother was overcome with hysteria and depression and ended up in the same mental institution where her husband had died twenty-one years before. The son visited her often, but never actually entered the hospital buildings. He met with her at the Grotto and strolled with her in the parklike grounds of the hospital. Well aware of the association between his father’s syphilitic insanity and his mother’s decline into mental oblivion, he nonetheless never once mentioned it in any of his countless letters.

8.

Though the pronoun “he” is used to describe Cthulhu and the other malefic gods from outer space, descriptions of these monsters serve to dissolve the boundaries between male and female. It’s sex itself—the body at its most primal, secret pleasure and secret contamination, consuming and being consumed—that makes men lose their minds. The smell of fish—the freshly exposed sea-bed—the “stench as of a thousand opened graves.” How many juvenile jokes did the boy hear, turning away in disgust and embarrassment, about the scent of female flesh? (After her first experience of sex, when Eve washes her genitals in a stream, Jehovah says with a Jewish commedian’s dismay, “Oy! Now, I’ll never get the smell out of the fish!”)

Like my father, an only child living with his widowed mother and two aged female relatives, he grew up in an atmosphere in which women had power. Like many boys born in the late 1800s, he was dressed as a girl and had long pretty hair. But unlike most boys of his generation, he was mollycoddled like a genius-prince. Surrounded by women who allowed his imagination to do as it pleased, the pampered boy lived in a confused fantasyland where male sexuality of any type was anathema.

In his stories, he often employed the word “unutterable,” and then continued to utter at great length. What is outside our world? What is beyond the “Wall of Sleep”? What is it we can’t express with words, yet which we try again and again to encompass with our logomaniacal scribblings?

“What language can describe the spectacle of a man lost in infinitely abysmal earth; pawing, twisting, wheezing; scrambling madly through sunken convolutions of immemorial blackness without an idea of time, safety, direction or definite object?” What language indeed?

Another of his favorite words is “titter.” He uses it to evoke evil, insanity, otherness. Again and again, his main characters lose their grip on reality when they learn secrets that no human should know. Like an avalanche, the knowledge overwhelms their minds and they often end up in asylums, tittering to themselves or hearing this supposedly obscene sound. People do a lot of gibbering and bleating too in these stories: using wild, incoherent, animal-like speech. In short, language itself decays into mere noise.

Even the name of his most famous creation is literally unpronounceable. In a letter to a pen-pal, he claimed that the name Cthulhu “is supposed to represent a fumbling human attempt to catch the phonetics of an absolutely non-human word. The name of the hellish entity was invented by beings whose vocal organs were not like man’s, hence it has no relation to the human speech equipment.”

9.

One of the earliest Cthulhu mythos stories, “The Nameless City,” takes the reader to an ancient necropolis uninhabited by living beings. What happens there? Almost nothing, beside piling up obscure adjectives and otiose adverbs. Yet he told one of his pen-pals that he had “labored long on the story, tearing up two beginnings and only reaching the desired atmosphere on the third attempt. I aimed for a cumulative succession of horrors and felt that I had achieved a pleasingly shuddersome effect.” In the first two drafts, it has been conjectured, he actually dared to use the name Rochester, but obliterated all trace of this place he so hated.

In another story, he again approaches his worst fear, then retreats behind a smokescreen of verbiage. “Old graveyards teem with the terrible, unbodied intelligence of generations.” He does not identify Mount Hope, home to his ancestral dead—and mine—but where else would he have to face what he most dreaded? “The Unnamable” barely qualifies as a story. It begins with the narrator and a friend lounging on a dilapidated tomb in an old burying ground, “speculating about the unnamable.” Impressed with a giant willow, he made a “fantastic remark about the spectral and unmentionable nourishment which the colossal roots must be sucking from that hoary charnel earth.”

Not much happens, beside the narrator’s friend chiding him about his “constant talk about ‘unnamable’ and ‘unmentionable’ things.” Then follows pages of obsessive blithering about a place where “lurked gibbering hideousness, perversion and diabolism. Here, truly, was the apotheosis of the exquisitely, the shriekingly unnamable.” What is it that haunts this Beautiful City of the Dead? He uses twenty words, when one—syphilis—would do: “so gibbous and infamous a nebulosity as the specter of a malign, chaotic perversion, itself a morbid blasphemy against nature.”

The story ends in a paroxysm of drivel. “It was everywhere—a gelatin—a slime—yet it had shapes, a thousand shapes of horror beyond all memory. There were eyes—and a blemish. It was the pit—the maelstrom—the ultimate abomination. It was the unnamable.”

10.

Fleeing this prophet of mad gibberish, I return to the cassette and Lord Rochester’s far more coherent, if no less baleful, creations. As I watch the tape snake through the machine, I submerge myself in his poetry, equal parts despair and wit. “Upon Nothing” is a meditation on exactly that: nullity, absence, obliteration, the eternal void. Another poem, a translation from an ancient Latin tragedy, dives as deeply into nonexistence. Soaked in reverb, dripping with grim glee, the voice could be speaking from the outer reaches of Ultimate Nowhere.

After death, nothing is, and nothing, death:

The utmost limit of a gasp of breath.

Let the ambitious zealot lay aside

His hopes of heaven, whose faith is but his pride;

Let slavish souls lay by their fear,

Nor be concerned which way nor where

After this life they shall be hurled.

Dead, we become the lumber of the world,

And to that mass of matter shall be swept

Where things destroyed with things unborn are kept.

Devouring time swallows us whole;

Impartial death confounds body and soul.

For Hell and the foul fiend that rules

God’s everlasting fiery jails

(Devised by rogues, dreaded by fools),

With his grim, grisly dog that keeps the door,

Are senseless stories, idle tales,

Dreams, whimseys, and no more.