1.

I am not a conjureman, calling the dead back to the land of the living. Nonetheless, I am here, finally, to perform the graveside rite so that I can be free.

Over a decade of inquiry, countless miles of meandering travel, paging through the tatters of newspapers, talking with old men about older times, sitting alone in musty churches, years of haunting this landscape, and today I find the grave.

Father Charles Flaherty has lain undisturbed here for exactly the number of years he walked the earth. And now, today, I take the role of the exorcist, waking the priest so that both of us can sleep undisturbed.

The book I’ve struggled—off and on—to complete has finally been published. Now, his secrets are public domain, and my imaginings too are there for anyone to investigate, ponder, condemn, embrace or reject.

Down below, bedded inside the earth, hidden like a seed in its brittle wooden jacket, the Crimson Priest lies sleeping in his burial box. After eighty-some years undisturbed, he hears my rusty shovel scraping above his head, and the stiff metallic hiss of my garden shears trimming the grass around the stone.

I’m here to set him free and at the same time to undo my own imprisonment. I understand who he is—and what he did—even if all who knew him in life chose to forget, or pushed the memory away and then took the truth with them to their graves. After all my dead-ends, sudden epiphanies, hard work, and dumb luck, I know him better than anyone yet alive.

The cemetery is unmarked, but not unkempt. Someone cuts the lawn now and then. Somebody plants stiff little flags—black and white emblems for the Knights of Columbus, not the stars and stripes. The roads are two lines of gravel, with barely room for a car to pass between the oaks and maples.

The priest’s monument is impressive for such a modest graveyard. A pretty stone maiden on one knee aims her passionate gaze upward. She points with one hand to heaven and with the other clings to the stone cross like the girl on ten thousand Rock of Ages tattoos. On the base are eight names: Donovans, Moores and Flahertys. Around the stone is a tight solid cordon of Irish dead: Fitzgerald, McGivney, Delaney, Keane, Ahern, Moroney, Maloney, Glynn and Sullivan.

Ireland in America: canal diggers and railroad bullies, poets and prize-fighters, bedraggled mothers with their hordes of children, politicos and countless cops. And one priest who has haunted me since the day I first encountered his name and his legend in a cheap little book of local history: “Father Flaherty: Devil or Saint?”

Now I take a slug of John Powers, and mutter a profane prayer, mangling together the Irish tongue and pious Latin. Uisce beatha—the water of life. Sub species aeternitatis—under the aspect of eternity. Another slug and then I splash the rest of the whiskey on the stone, on his name: Father Charles Flaherty.

2.

It was clear to me that I needed music for this rite. So I dug out the vinyl albums recorded by John McCormack while the priest still lived; and I unearthed the cassette I bought in a little music shop in Tralee: Rum, Sodomy, and the Lash, by the Pogues—dirty, loud, not bittersweet but bitterly funny, full of heartache and whiskey. Some of McCormack’s recordings are over a hundred years old: “Macushla,” “Mother Macree,” “Molly Bawn” and “Molly Brannigan.” Some of the Pogues’ songs come from a deeper past, folky and fierce, the old sounds of lost Ireland comingled with punk rock snarls.

Pairing John McCormack with Shane McGowan—front man for the Pogues—is both sacrilege and celebration. McCormack has been called the greatest Irish tenor who ever lived. With world-renowned vocal quality and handsome charm, he made hundreds of recordings and played the most prestigious venues around the globe. Shane McGowan was a wretched drunk and drug addict, by the end bloated, incoherent, and toothless. Nonetheless, they are the taped voices—both of them—that I bring with me to Flaherty’s grave.

I park as close to the big stone as I can, and leave the car doors open so that the music is mine as I kneel and dig. The weather is fair, and yet I see not a single other pilgrim in the graveyard this day.

After the hundred-year-old rendering of the achingly sentimental “Mother Macree,” I listen to the Pogues’ “Sick Bed of Cuchulainn,” which reaches much father back into mythic time. Shane addresses an unknown “you,” beginning with an evocation of MacCormack “singing by the bed.” There’s “a glass of punch below your feet and an angel at your head.” There are also bottle-bearing devils on each side, offering “one more drop of poison.”

Human wreckage, Shane McGowan is finally dead. Now I feel him singing to himself, as he sees forward to the day when a great Irish tenor and a great Irish warrior would usher him across to the next world.

3.

And what happens at the priest’s grave? The granite maiden points with rapturous confidence toward heaven. Her cross stands strong. The Irish whiskey works on my brain and on the stone. Uisce beatha—the water of life and the water of oblivion. Words work too. “Sub species aeternitatis.” Latin is the language of nearly-lost magic—pagan Rome preserved in the tongue of dead priests. Though my hands are dirty and my ears are filled with the Pogues’ wild revels, I’m now under the aspect of eternity. My thoughts penetrate the earth and the past. That’s where I’m going today: down and back.

It’s no black mass that I celebrate on a warm Spring afternoon, but a crimson mass, for a crimson priest. He never wore the red robes of the cardinal. It was his name, his conduct, his reputation, his legend, that gleamed brilliantly red. An inner crimson: the pulse of blood, the spirit of ancient feuds, the Sacred Heart, writhing flames, rage and roses. He wore black all his adult life but the crimson inside shone through.

I’ve uncovered the evidence, both of crime and innocence. Photos, court documents, long-lost newspaper articles, and actual witnesses. I sat once with a ninety-year-old man, directly across the street from the house where Flaherty lived his last years, and took his testimony. “He had his own altar. He said mass there. I saw people come and go. He wore the priest collar ‘til the day he died.” I know more than anyone alive about Charles Flaherty’s many times in court, his removal from the church, his rebellion against the bishop, and the guns at midnight mass. I also know about his hundreds of faithful followers (mostly women) who never once accepted his convictions and jail time as anything but dirty politics and old Irish clans mad for vengeance.

What happens today at his grave? A voice echoing from below? The earth opening and priestly tendril fingers reaching for me and my soul? I feel fine whiskey and read forgotten names. I see what no one else can see.

His skeletal remains are dressed in black priestly cassock. One boney hand holds a rosary and the other holds a cross, as though to keep away grave-breakers such as I. He wants peace and so I’m certain too that he blesses my efforts. After all, I’m the one who dedicated years to clearing his name of charges, true and false.

I am his confessor and he is mine. Never once having been in the whispering sin booth, I prepare to make my confession in the open air, at his grave. “Bless me Father, for I have sinned.” Isn’t that how it starts?

4.

Though the newspapers reported “The Case of the Bloodless Corpse” in painstaking detail, it quickly evolved from actual criminal investigation into legend. This much is certain: a woman’s body washed up on the shore of Lake Ontario. She was nude, all her hair had been removed, and all the blood drained from her veins. Father Flaherty spent a great deal of time, money, and bold oratory attempting to prove that the body on the shore was not that of his housekeeper. No indictments, no arrests, and no convictions were ever associated with the case. The identity of the bloodless corpse was never firmly established. Buried and exhumed, buried and exhumed again, it now lies in Mount Hope Cemetery under the name Vivian Thompson Jennings. There is no stone, but I have searched the cemetery records and stood at the spot where the woman was finally laid to rest.

In his last known interview, at age seventy-nine, Father Flaherty denied any connection to the exsanguinated body and the still-unsolved mystery. It had been ten years since his housekeeper had disappeared and was never heard from again. In the interval, Flaherty had spent almost four years in state prison. Though time had passed, people still knew the name, and the reputation, of the old priest. Nearing the end of his life, the legend continued to hang on in the Genesee Valley. The old man was seen, dressed in the garments of a priest, swinging a knobbed blackthorn shillelagh as he trudged the misty backroads and byways.

At the peak of his notoriety, Flaherty’s repute extended across the entirety of America. From the hinterlands of western New York State, his story reached readers on the far side of the nation. Newspapers ran hundreds of columns on the renegade priest accused of fathering a child with a fifteen-year-old girl. (I spent months digging to find the record of his final acquittal.) Over the years, the press continued to record his occasional defeats, more common improbable triumphs, and his final “crucifixion”—as he called his conviction for performing abortions in 1927 and the failure of his last appeal.

To this day, certain descendants of Flaherty’s opponents, even though they were only children when he died, still seethe with a highly-charged mixture of grief and hatred when his name is mentioned. His aged enemies continue to curse the priest, given the list of charges ultimately laid against him: fraud, forgery, statutory rape, practicing medicine without a license, practicing law without proper credentials, bribing witnesses, perjury, tampering with evidence, altering legal documents, obstructing justice, disturbing the public (that is: fist-fighting on Main Street with the sheriff), contempt of court, manslaughter, performing “illegal operations” (that is: abortions), fornication, and first degree murder.

It took thirty-four years for the authorities of Livingston County to put him behind bars. A careerist district attorney did succeed at last, and Flaherty spent almost four years in Auburn state prison, where from east windows he could look down at the high school he’d attended, and farther off see the spires of the Church of the Holy Family, where he’d served as an altar boy.

Though legend has it otherwise, he was never excommunicated. As he proudly and repeatedly asserted, he was never tried nor censured by any ecclesiastical court. He remained a priest until his death, which means that from the moment he was ordained he possessed what some call “Power over the sacred.”

Decades after his death, there are also people in his hometown who speak of him as a holy man. There is admiration, respect, even awe, in these fierce loyalists. He aided the sick and poor without asking for payment, he stood up against corrupt and racist political power, he won far more court cases (without ever being admitted to the New York State Bar) than he lost. He risked a great deal—his good name and his freedom—to make certain that those without a voice would be heard and those with no power would not be crushed by the powerful.

William Keating, his last chauffeur and bodyguard, instilled in his daughter Charlotte respect bordering on veneration. He told his daughter more than once, “Whatever Father Flaherty says is the word of God.” When I met Miss Keating, over ninety years old, she pulled aside the collar on her dress to show a scar on her neck and declared, “Look here. See that? Father Flaherty did that. He operated on me when I was a little girl.” The scar, the genuine physical evidence remains: puckered and faintly pinkish tissue. Flaherty had used a surgical lance to drain the infected cyst, and a scalpel to remove it. “My father said that he saved my life.”

5.

He may be a corpse, but he’s still a priest. Once ordained, a holy man’s nature cannot be altered. He is always a priest, even if he’s prevented from using his powers. Beyond death, the power is still there, lying dormant.

In Father Flaherty’s day, a discarded handkerchief, the few hairs from his brush, whiskers in his sink, crossed-out notes for a sermon—all of these had power. His followers would collect them, save them away in envelopes. A discarded umbrella too was rich with magically properties. His followers would even dab a cloth on the church floor to capture a spot of his spittle. When his prayers became loud and excited, his women would kneel down with a cloth and keep it like a relic, imbued with almost as much power as the funeral earth I’m digging and taking away in an old coffee can.

Dirt from a priest’s grave can make strong sorcery. Unlike traditional goopher dust—which must be collected from a grave under a full moon at midnight—this pound of gritty powder is scraped together in full sun. I kneel and John MacCormack sings “I Hear You Calling Me,” the record that sold more copies than any other he made.

You called me when the moon had veiled her light

Before I went from you into the night.

And on your grave the mossy grass is green

I stand—do you behold me?—listening here

Hearing your voice through all the years between.

6.

“It’s in Latin,” the church secretary had said over the phone, and read a phrase that didn’t mean anything to me. This—over a decade ago—had been my entry into Father Flaherty’s world. My search ends at the priest’s grave, listening to dead Irishmen; it had begun in the parish office of a rural church about an hour from where I live.

I had put in some calls, making tentative inquiries. While the secretary was still on the phone, she got her hands on the book where Flaherty had recorded baptisms for eleven years. “He had beautiful handwriting,” she said. “Now, why do you want to see these records?”

I didn’t have a ready answer. And I asked myself the question that would appear again and again during my search: why was I poking around in someone else’s past? Who, if anyone, had a legitimate claim to this story?

“Do you have a family connection?”

“No. Not exactly,” I said. “I’m doing research.” This was true enough, though vague and noncommittal.

The secretary was pleasant and easy to speak with. Yet she was hesitant to allow me access to the register. “We can’t have you just poking around through the parish records. Some people might not know that they’re adopted. Or born out of wedlock.” The records are over a hundred years old, and still she was hesitant.

I said I understood, and wanted to respect people’s privacy. But again, I sidestepped the question of my real motivation. This wasn’t out of dishonesty. I truly didn’t have a clear understanding for myself, though it was much more than idle curiosity that drove me.

I asked if I might look at the record book. She agreed, and a few days later I found the parish office—right across the street from the courthouse where Flaherty’s first trial had taken place.

The secretary was careful about letting me look at, and touch, the six tattered pages where Father Flaherty had recorded baptisms between 1882 and 1893. She was right: he did have beautiful handwriting, much more elegant than the priests who preceded and followed him at St. Patrick’s.

This was my first contact with something physical that Flaherty had touched. He’d moved his fountain pen there, putting his name hundreds of times on the pages. He signed himself “Chas.” with a flourish on the C and the S. Fine, clear, distinctive. The moment was suffused with uncanny power, as though these crumbling sheets of paper were relics, as endowed with power as the saint’s clothes and bones I’d seen in Cathedral reliquaria. Power—not bland bureaucratic holiness. Power—somehow intrinsic in the Latin phrases and elegant signatures.

Four columns: names of the parents, dates of baptism, names of the godparents, and the signature of the priest. The previous pastor at St. Patrick’s had signed only once and left the rest of the column blank. But Charles Flaherty signed every line for eleven years, six pages of his name, an insistent visual repetition or a steady self-declaring rhythm, as though he wanted to make sure he wasn’t forgotten.

7.

After MacCormack’s glistening bell-like pianissimo, the Pogues are back, rattling around the gravestones. Shane McGowan died at age sixty-five; he was in his mid-twenties when he laid down these gloriously ramshackle tracks. The cassette is forty years old, so I hear some wobble and hiss. But still the howls and growls, hoots and bellows, come through like a gang of filthy, drunken angels’ early morning clamor.

“The Old Main Drag” is a young man’s song. But Shane looks forward through the decades, describing “the old ones,” whose ranks he would one day join, the wretches who “dribble and vomit and grovel and shout.” Shane and I were born within a year of each other. He went down the path littered with empty pints and quarts, dirty needles, and tossed-away pill bottles. I didn’t and I’m still alive, though I spend more time in graveyards than anyone I know.

In “Down in the Ground Where the Dead Men Go,” Shane sings about roaming Ireland like a ghost. “I can’t forget,” he declares, “those things I saw.” Drunken visions of hell or something far more troubling, because far closer to the truth? A glimpse into his future.

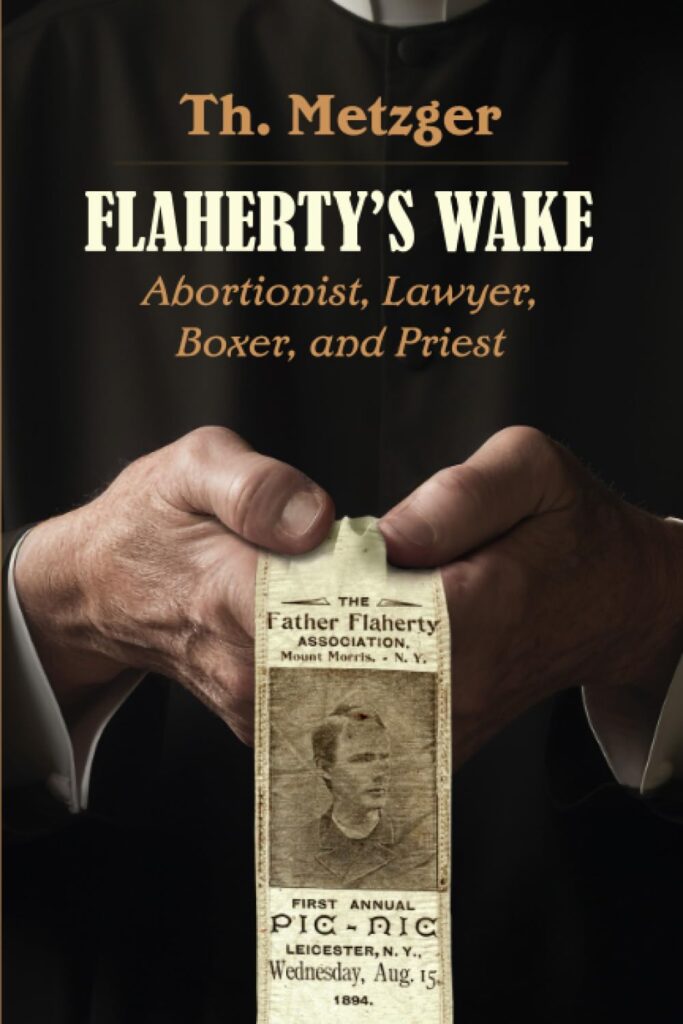

I too can’t forget. Or perhaps it’s more complicated: I won’t allow myself forget. A picture of Father Flaherty hung in my bedroom for years. It’s printed on a ribbon, worn by a celebrant at the first annual Father Flaherty Society picnic. It shows him as a young man, before the crimes—true and false—before the trials and self-inflicted tribulations. I’ve brought the picture to the graveside, along with a stack of newspaper articles painstakingly printed from frayed and faded microfilm, and copies of letters in his beautiful hand. Shall I burn them all to free myself, bury them, or soak them in tears and whiskey and let the wind and rain take them away?

To my knowledge—and no one knows more about the priest than I do—he never once performed an exorcism. Hundreds of baptisms, dozens of funerals and weddings, countless small acts of blessing—and never once did he expel malign supernatural forces by the power passed on to him at his ordination.

“Father Flaherty—Saint or Devil?”

I’ve also brought along Genesee Valley People, the book—long out of print—where I first read about the priest and his exploits. It’s cheaply made, published by a local press, with illustrations that are copies of copies of copies. The chapter about Flaherty is only nine pages long, and as I learned through my searching, rife with errors, but it was enough to start me on this shadowland journey. “Saint or Devil?” The answer is of course neither and both.

It’s unlikely that anyone other than I will make the case for his beatification. Though the Roman church burnt some holy people at the stake (e.g. Joan d’Arc) and only then bestowed on them sainthood, I doubt Father Flaherty will make the same kind of transition. Ordination, incarceration, veneration. And while Saint John Chrysostom said that hell was paved with the skulls of priests, I find it hard to imagine Flaherty enduring eternal punishment, or as a proud devil, inflicting it on others.

However, saints and devils are imbued with one property that Flaherty too possessed, Sub species aeternitatis. At his ordination he was given power over the sacred. Broad-shouldered, square-jawed, and hard-fisted, he had the strength and nerve to box with John L. Sullivan, the heavyweight champion of the world. Hated by some and revered by others, he still divides his church into factions which continue to carry on their spiritual battle. He has, in short, what saints and devils both can claim: immortality.

The gravestone would take ten men with winches and chains to remove. Yet it cannot hold the priest down in his bed of sanctified earth.

8.

I’ve brought one more item to the graveside: a penny whistle that I bought in the same store in the west of Ireland where I found Rum, Sodomy, and the Lash. The box it came in is a bit tattered, but I’ve kept it there over the years. Unlike modern instruments, which are just a chromed metal pipe with a plastic mouthpiece, my “Original Clarke Penny Whistle” was made by traditional methods: black enameled tin, with a wooden stopper to split my breath and draw out the piping sound.

The great tenor is gone now, and the wild Irish boys too have been wound up in their tape spindle shroud. It’s up to me to offer the closing song. I wipe my hands, stained with priest-dirt, as best I can. The sound I make is neither MacCormack’s beautiful croon in a susurrus wash of surface noise, nor the Pogues’ drunken gleeful jig-and-reel. I’m no virtuoso on the penny whistle, but I’ve picked it up now and then over the years, and mastered it enough to play a number of old tunes.

First is “The Parting Glass.” Shane is silent, yet as I play, I hear his gravelly voice inside my head. But since it falls unto my lot that I should rise and you should not.

Then I attempt MacCormack’s “I Hear You Calling Me.” His rendition reaches skyward, soft and effortless. The penny whistle doesn’t come near such sweetness.My heart still hears the distant music of your voice. Living in an American Irish enclave, Flaherty would have known both these songs.

Perhaps not so with the tune I leave him with. “Brian Boru’s March” reaches deep into tradition, its origins lying so far back that it has been called the sound of primal Ireland. It’s unlikely that Brian Boru, (who lived over a thousand years ago) ever heard the tune. Still, it conjures the High King, his wars of conquest, his rise and reign, his battle to free Ireland of Viking domination. How much is true and how much is legendary: all of this is irrelevant to me. As with the priest, I care only about what was said and what was remembered—and by whom.

There is no recording of Flaherty’s voice. I’ve read his letters, his statements to the press, his arguments in court. So, I have some idea how he used words to present himself. But the actual sound of his voice—that is gone and cannot be reclaimed.

I fumble the notes, and start again. “Brian Boru’s March” wafts over the graveyard. Something, someone, stirs beneath the sod. A ghost, a demon? Hardly. This may be an exorcism, but it’s not a horror movie. The music is wistful, not grim and foreboding. The sun shines brightly, drying the whiskey stain on the Rock of Ages. I’ve come to make my farewells, not unleash the dead.

Neither a dance tune nor a song of sentiment, the High King’s march—as I first heard it on a record made over fifty years ago—comes in from the distance, builds and swells, then moves off, dwindles and is gone. The ancient hero appears out of the mist with his band of devoted followers, heading for the battlefield. The Father Flaherty Association also marched: down Main Street, with a brass band in front, men brandishing shillelaghs, and the woman working their rosaries and murmuring prayers—in Latin, English, and Irish.

I play the march two, three, four times, and then let it drift away. I take my tin whistle, my can of priest dirt, my empty bottle, and return to the car. On the long drive home, I hold the silence.

9.

The can of sanctified graveyard dust and the bottle that had held the water of life stand sentinel behind me as I write these words. John MacCormack and Shane McGowan are out of sight now; their songs, both sweet and raucous, are no longer needed. The priest and I have made our peace.

Th. Metzger’s biography of Father Flaherty is available here.