Akhmatova was born in 1899, well-educated, of a noble, land-owning family. Evening was published in 1912, when she was twenty-three. It inaugurated a new epoch in Russian poetry. Each poem condenses into a few lucid stanzas the emotional depth one might expect of a great psychological novel. Nothing like it had ever been seen, in Russia or elsewhere. It sold out edition after edition, and became the Bible of Russian lovers.

The book found many imitators among literary ladies. Told, “You have given Russian womankind a voice!” Akhmtova replied, “Yes, but now how do I get them to shut up?”

Akhmatova had a gift for depicting physical things in a way that carried psychological meaning. But she was not simply manufacturing metaphors. Her images have a photographic precision that makes them too concrete to be simply symbols. And they are not photographs, because they capture not a moment, but a narrative. They have a momentum. Akhmatova’s imagery is cinematic.

Powell’s complete translation of Evening is available for purchase here.

Part Two of Akhmatova’s Evening

Disloyal

I

On the terrace, a morning in spring ,

a morning drunk with sunlight

If the scent of roses were a thing one could hear,

you’d call it deafening,

and the sky’s more luminously blue than faience.

I read an album, bound in soft morocco,

my grandmother’s—in her day

gentlemen callers penned gallant stanzas,

love-lorn elegies, in just such books,

for girls whose French was flawless,

who played piano charmingly,

and had a pretty gift for watercolors.

From here I can see up the road

as far as the gate, the fence-posts are very

decidedly white against the turf’s

jewel-tone green. The flowerbeds are bright

in their dappled gladness. How sweet

is love, how rashly, without looking,

the heart pursues it! The sky clouds over

for a moment and a raven interjects

his gurgling croak. Down that woodland path

you can just make out a gravestone’s oval arc.

II

The wind holds its breath,

as if to let the day’s heat sink in.

All is motionless—a real “still life”—

as though the sky were a bell jar

of cobalt-blue glass

enclosing a Victorian

taxidermy nature display.

The woven-in flowers that haven’t yet

shaken loose from my braid yield a scent

as dusty as if they were dried.

On the fir tree’s rough gnarled trunk

is an ant-highway.

The distant pond glimmers

its dull, unambitious silver.

Who will be caught up into my dreams

today, as I nap through the heat

in my hammock’s multicolored net?

III

Azure evening. Late summer.

The wind is blowing gently now.

It’s still light late. The sky’s particular tint

of brightness now means I need to head home.

Who’ll be there? I’d guess my fiancé.

That is my fiancé, isn’t it?

Someone’s on the terrace, I recognize

his silhouette. Then comes a conversation

in hushed, low tones, then comes a captivating

languor such as I’ve never known.

The poplar trees rustle as though tender dreams

had made them tremble.

The sky has darkened to a steel blue,

a few pale stars appear.

I bring a little bunch of gillyflowers

for someone. The purple of their petals hints

at a fire repressed, unexpressed, but which he’ll touch

in the warmth of my palm as he takes

the blossoms from my hand,

my hand too timid to just reach out to his.

IV

I finally wrote him the words

I only had the courage to say in a letter.

My head vaguely aches,

and, weirdly, I feel everything less.

The last hunting horn of the season

has since sounded in the distance,

if it echoes still, it’s only in memory.

All that I felt for him baffles me now.

The first faint dusting of autumn snow

has fallen on the lawn where we played croquet.

Let the last late leaves on the poplar trees

have their rustle—I no longer listen to their whispers;

the old, tormenting ideas

are worn out with rethinking.

I’ll be happy. I won’t spoil

your oblivious, customary fun.

I’ve forgiven the cruel, joking words

I’m sure you don’t even recall having said.

The lips that spoke them are dear to me still.

After all, tomorrow, you’ll be here,

along with the first real snowfall.

They’ll light candles in the dining room,

more tender is their shimmer in the light of gray day.

On the table, they’ll set roses from the greenhouse,

like summer recovered, a whole great bouquet.

Paris, 1911: A Drunken Day with Modigliani

You’re so much fun when you’re drunk,

even though your stories don’t make any sense.

The elm trees’ leaves turned early:

autumn’s yellow pennants.

We’ve wandered into a wonderland

too seemingly real to be so.

We should feel terrible about it,

so what are we doing with these fixed, silly grins?

A little bitterness, please, for the sake of decency!

There’s no excuse for this placid happiness—

be that as it may, I won’t abandon you,

my tender drunken buddy.

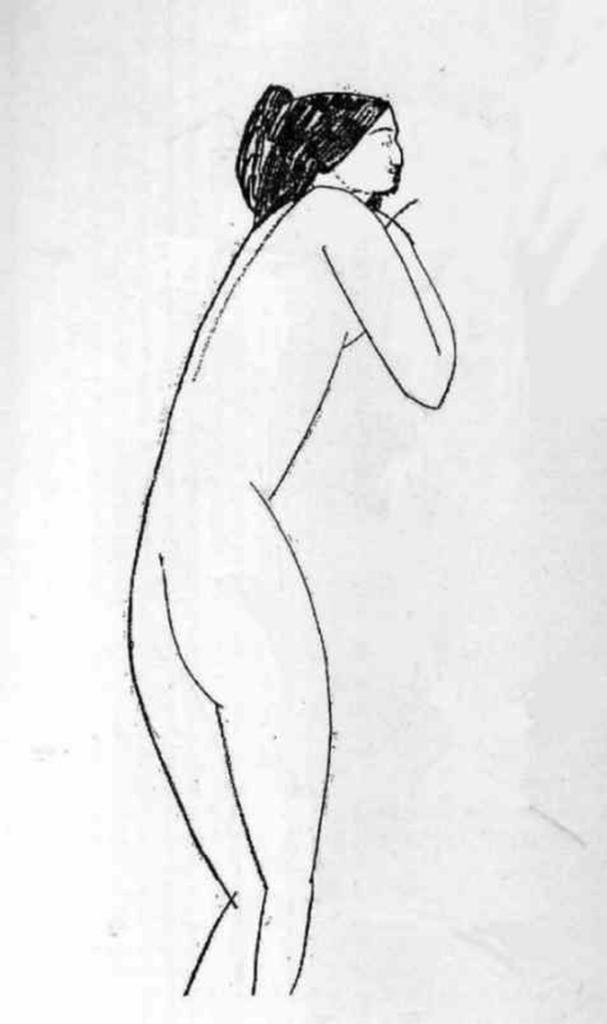

Modigliani, drawing of Akhmatova asleep, 1911. Public Domain.

My husband took that handsome, patterned belt . . .

My husband took that handsome, patterned belt of his,

folded it in two, and gave me quite a hiding.

I wait for you, peering through the little hinged window

that lets in a breath of winter

when the stove-warmed air inside gets oppressive.

All night I sit here, lamp in hand,

and it’s getting to be day. Smoke’s rising now

from the blacksmith’s chimney.

Again you couldn’t find the time

to stay a night with me, to cheer me

here in my miserable prison.

It’s for you I go on living, accept

my dreary, hurtful lot.

Did you find someone new? A blonde?

Or is she a redhead, your new girlfriend?

Even thinking this makes me groan out loud.

When the night’s too black, the eye can’t see;

when the air’s too close, you can’t even breathe;

this weight is more than my heart can take.

You couldn’t have made me feel more stupid

if you’d made me drunk. Morning’s rays

just touch the unrumpled bed

where no one slept.

Whatever it is that truly unites . . .

Whatever it is that truly unites

two hearts, it isn’t manacles.

So, go, if you want to. There’s happiness

a-plenty out there, ready for those

whose road is open, for the free.

I’m not crying. I’m not even complaining

that happiness just didn’t happen for me.

No, don’t kiss me. I’m tired.

When death comes, he can kiss me goodnight.

I’m exhausted. So sharp was the pain,

endless the days without you, and relentless

as the whiteness of winter.

Why oh why did you have to be

so much better than the man I chose?

On my knees at sunrise . . .

On my knees at sunrise in the vegetable patch,

humming a love song, yanking out goosefoot,

tossing the stalks: they’ve tiny clustered flowers,

velvet blue-gray leaves shaped amazingly

like real geese feet.

Forgive me, pretty weeds!

I look up: by the rustic fence

woven from branches and twigs,

a barefoot girl is crying.

Her high clear voice of painful fear

is harrowing. The scent

of the goosefoot’s murdered stems

gets more intense in the sun-warmed air.

“What man is there of you, who, if his son

ask bread, will he give him a stone?”

That’s the hard prize my deliberate deafness

will earn me. Above, there’s only cloudless sky,

and all I can hear is that little girl’s cry.

I wandered here, without meaning to . . .

I wandered here, without meaning to.

A girl with nothing to do,

I could just as well not do it here

by the motionless mill

on a sleepy little hillock.

I don’t need to say anything,

not now, maybe not ever.

It’s August, over a wilting morning glory

a bee swims gently through the air.

I salute the rusalka, the naiad of the mill pond—

the souls of girls who drown themselves

because of being jilted, because of cruel husbands,

or on account of unwelcome pregnancies—

girls for whom water seemed to offer

a less cruel solution—these become rusalki,

sometimes playful, sometimes dangerous,

nixies of fertility, strongest in spring—

but it seems the spirit mistress of this particular pond

has passed away.

A rust-colored slime

has overspread her waters, formerly wide,

now shallow and shrunk from a whole summer’s heat.

A moon glitters in the blue

above the yellow, flickering leaves

of the trembling aspen.

I notice everything now,

it all seems somehow new.

The humid wind through the trees

reeks of moisture. I’m silent, a part

of this soundless place, I’m ready

to cease being and return to you, earth,

to let my estranged nature be reabsorbed

into the strangeness of nature.

Night fell. I didn’t even lock the door . . .

Night fell. I didn’t even lock the door,

didn’t light a lamp;

you don’t know how exhausted I was,

how unable to accept

that there was nothing to be done

but go to bed—

so I watched the last red-yellow

summer sunset streaks expire in darkness

past the fir trees. You don’t know how drunk

I suddenly felt when I heard a voice

I thought was yours,

I understood then hellishly well

that I’d lost all.

Oh, how certain I’d been

you’d come back.

We shelter from the sun in a threshing barn . . .

We shelter from the sun in a threshing barn.

It’s empty, offers shade, but it’s hot here too.

I laugh while I cry in my heart for sheer frustration.

My old companion whispers,

“Don’t give in to gloom, we’re on our way to better!”

I don’t believe my ancient friend.

He’s laughable, a wretched, blind old man

who’s measured out his life, step by careful step,

every road he took was boring and long.

I hear my own voice ring out, shrill and brittle,

the voice of folk who don’t know what “happy” even means,

“Our packs our light, the atmosphere is heavy

with impending weather, tomorrow

we’ll be hungry in the rain.”

Hide me wind . . .

Hide me wind,

cover me with dead leaves

and dust from the road, let that be my burial.

No kin came. You, wind,

are the only living witness to my end.

Evening aimlessly approaches above;

along with cooler, easier, evening breeze,

the breath of the land at rest.

I was once as free as you, wind,

but that wasn’t enough—

I also wanted to live!

You see what that won me. Look at me; lone,

cold as the corpse I soon shall be,

a dying woman whose hands none will fold.

on my dead chest.

Come wind, cover my heart if you can,

bandage the dark hurt of it,

and let the night shroud me in its dark,

let darkness be my shroud.

Command the breeze to whisper a prayer—

the blue mist of evening soothes like a psalm—

easing my way, alone as I go

into my final dream.

Make the reeds roar, O autumn wind,

with sudden gusting,

a bitter fitful hymn

for all my vanished springs.

Believe it. This fever that weakens me . . .

Believe it. This fever that weakens me

like loss of blood, wasn’t caused by the sting

of a serpent’s poison tooth.

In a white and a wintry field,

on a white and wintry day,

I became a shy girl who tries to sing back love

in the voice of a little lost bird

There’s been no path back for a long time now,

every other road is closed,

my prince, my tsaryevich, is in his tall fortress,

his kremlin. Is there any way

I can trick him into loving me again?

I don’t know how. All I do know

is that life on this earth is a cheat.

No forgetting how he came to take his leave of me.

I didn’t cry. It was fate.

Now I cast nightly spells so he’ll dream of me.

My magic has no power.

That’s why he sleeps so easily,

troubled by nothing, and I’m out here

staring at his high barred gates—

or has a sirin perched above his bed,

a sirin, half-woman, half-bird,

with a tender expression in her shining eyes—

the sirin’s proper roost is that famous tree in Eden,

she’s only seen by happy people.

Who hears her song forgets all else.

Surely some such bird

has already taken my place,

and is singing my tsaryevich her siren song.