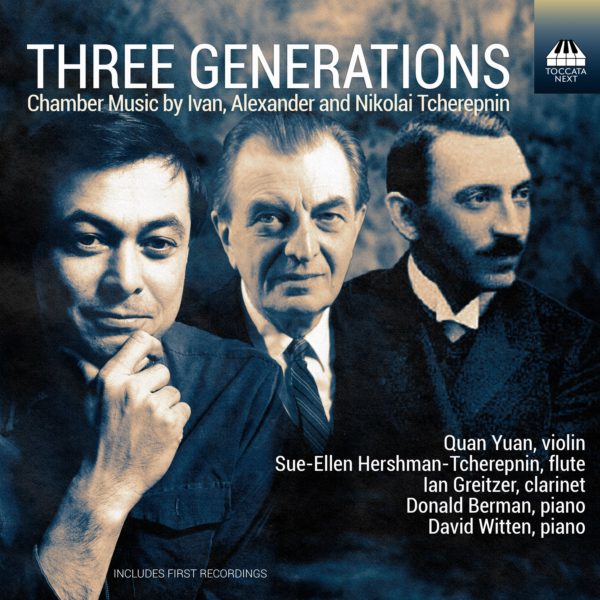

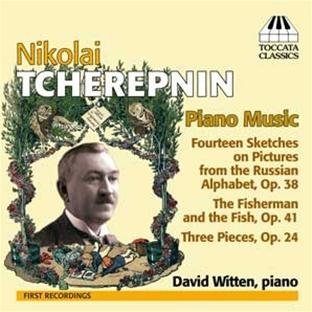

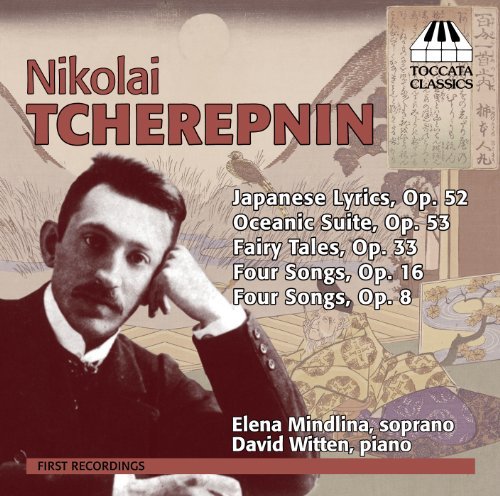

Three Generations, Chamber Music by Ivan, Alexander and Nikolai Tcherepnin, David Witten, piano; Quan Yuan, violin; Sue-Ellen Hershman-Tcherepnin, flute; Donald Berman, piano. Nikolai Tcherepnin, Piano Music; David Witten, piano. Toccata Classics 2011. Nikolai Tcherepnin, Songs; David Witten piano; Elena Mindlina, soprano. Toccata Classics 2014.

We have all had the experience, while driving, of hearing something wonderful on a classical station without being able to figure out who the composer was. In the days before station playlists were accessible on one’s phone, I have more than once sat in my parked vehicle, waiting for the DJ to come on and identify the piece.

It is with a similar sense of surprise and pleased discovery that I listened to this CD of chamber music by three generations of Tcherepnins, written between 1900 and 1996. If I didn’t have the liner notes before me, I would have guessed at the composers in vain, confident only that the work was of such quality that it must be by someone famous. Ranging from late Romantic to Modern (though considerably shy of atonality), the work is all delightful and surprising. Its natural audience will be those who are already familiar with the music of the clan’s patriarch, Nikolai Tcherepnin, but anyone who enjoys modern classical music in the Bartok to Stravinsky end of the spectrum will find much to enjoy here.

Lesser known composers are a special pleasure. The greats of a given period are, of course, great, but one sometimes ends up listening to them to the exclusion of their fellows, thus missing the musical context of the time. One forgets how refreshing it is to hear a different voice. To offer a parallel example, Shakespeare is wonderful, but if he’s the only Renaissance playwright you read, you miss out on the Jonson, Middleton and Webster, whose productions are at times not a bit inferior, and have the additional charm of the unexpected.

Chamber music involves a small group of musicians, small enough to fit into one ordinary chamber. In works of this kind, everyone has an independent part: they interact, they don’t play the same notes together. Witten has assembled a group of musicians with whom he obviously has real rapport, and all of whom are clearly having a very good time. The performance is flawless, has a genuine warmth, the players’ engagement is contagious. Some of the best recordings I have are, like this, by musicians few have heard of. The less than expert buyer of classical CD’s tends to favor well-known names, a caution that can impoverish our exposure to many outstanding talents.

To describe this CD in musical detail would entail technical terms which, even if I knew them, few readers would understand, while poetic descriptions of music heard are as ineffectual as posted photos of people’s lunches. A far better recommendation of this fascinating CD would be to describe the composer who is the focus.

Nikolai Tcherepnin is hardly a name to conjure with, even among Russians. Yet this fin-de-siècle composer, who conducted the orchestra for the Ballets Russes, and himself wrote a number of their ballets, was a member of that immortal crew which included Stravinsky, Nijinsky, Fokine, Diaghilev and Bakst—but he is, for most, less than a memory now.

Tcherepnin descended into oblivion with the birth of the Modern, while those of his fellows who forged ahead into the exciting unknown, for whom turn-of-the-century decadence and excess were merely an apprenticeship, are rather better remembered.

Thus Isadora Duncan is still revered: her rivals of the time, Louie Fuller and Mata Hari, who garnered just as much contemporary attention for wearing just as little, are just amusing footnotes. The Ballet Russes are remembered for Stravinsky’s new music and Nijinsky’s new choreography. The exotic costumes designed by Bakst and Benois, which Paul Poiret adapted to clothe Paris in “cloth of fire and joy” were little more than a brightly colored side-conflagration, soon extinguished by the genius of Coco Chanel.

Tcherepnin, alas, was on the wrong side of history. His music falls in that twilight region between the end of the Romantic period and the twentieth century. His is a voice out of Russia’s Silver Age, which James Billington, the great historian of Russian culture, describes in The Icon and the Axe as

. . . equally exotic and superlative. A feast of delicacies tinged with foreboding.

But now, two decades into the twenty-first century, we can take a guiltless pleasure in such extravagant and unwholesome bon-bons as Tcherepnin’s music. In the present cultural chaos, on the cusp of an ecological apocalypse, when (thanks to the Internet) all that was past is present, Tcherepnin is once more plausible, and David Witten has chosen precisely the right time to help restore him to the repertory.

Witten’s first Tcherepnin CD, Nikolai Tcherepnin, Piano Music, offers a judicious and impressive selection from the work. The early Three Pieces showcase his earlier High-Romantic style. The Fourteen Sketches on Pictures from the Russian Alphabet were written as musical interpretations of an alphabet primer for children (A is for Arab, B is for Baba-Yaga, &c.), illustrated by Alexander Benois. These are delightful inventions, in the spirit of Schumann’s 1835 Carnaval (short piano sketches of Commedia del’Arte characters). The pamphlet included in the CD reproduces all fourteen of the images, which add greatly to one’s enjoyment.

The last piece is a musical interpretation of Pushkin’s verse retelling of The Fisherman and the Fish, which was intended to follow, section by section, a reading of the poem. The full text is provided in the liner notes.

[Several of the illustrations may be seen, and some of these pieces heard, in the interview with David Witten in this issue.]

Speaking of the liner notes, these are the most insightful and well-composed we have ever seen—not surprisingly, they were written by Witten himself. Along with the Benois pictures and the Pushkin poem, they make this CD an extraordinary gift for any intelligent friend—an opulent invitation to explore the strange little Russian Oz of Tcherepnin’s imagination.

The music is excellent of its time and place and will delight anyone who enjoys Debussy or the Schoenberg of the Art Songs. Witten’s playing is flawless, elegant and expressive. He shows absolute fidelity to the spirit and letter of the music, to which he brings real feeling and even a certain playfulness. His interpretation is always intelligent, fully articulating the content, producing a compelling performance from which one’s attention never strays.

The most startling of Witten’s performances of this composer are to be found on Nikolai Tcherepnin, Songs. As Witten points out in his (again) exemplary liner notes, Tcherepnin was a master of the musical interpretation of texts—he wrote two operas, and his masterpiece, The Descent of the Virgin Mary into Hell (1930) expounds (in a menacing mixture or Modernism and Russian Orthodox liturgical tropes) a scripture from the Apocrypha. Early translated from Greek into Russian, this Dantean tour of the tortures of the damned became a Russian religious classic. A pity that this rarely performed setting of the text has not been recorded!

On this CD we hear Tcherepnin’s genius brought to bear on the poetry of Tyutchev and Balmont, whose work fits somewhere in the Symbolist to Expressionist continuum. The music is shimmering, undulant, otherworldly, and the soprano Elena Mindlina’s interpretation is poignant and eerily beautiful—all the more so since the words are all in Russian. A generous and well laid-out libretto accompanies the CD. A translation is provided alongside the texts in Cyrillic—actually a very reasonable choice. The Russian speaking listener can follow, and with abstract and allusive poetry like this, a transliteration into roman letters would really not have helped one who has no Russian. A general sense of what is going on, such as the libretto provides, suffices to give a rich aesthetic experience.

The last selection on the disc is eight songs from Balmont’s Oceanic Suite—a Cycle of Incantations. The poet traveled through Mexico, South Africa and Indonesia to find the raw, vital ethnographic inspiration for these poems, and they fully vindicate the name “invocations.” Addressed variously to Erebus the Maker of Shadows, the Earth, and the Agave plant, these are magical texts, and Tcherepnin does ample justice to them. Though he does not go as far into dissonant “primitivism” as Stravinsky did in his Rite of Spring, Tcherepnin shows himself a masterful composer of dramatic music, and the settings are credibly occult. I cannot guarantee that blasting these tracks will cause your neighbors’ milk to sour or their cows to miscarry, but who knows?

Mikhail Lermontov, A Hero of Our Time/The Demon, Mark R. Pettus translator. Reading Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time/ The Demon in Russian, a Parallel-Text Russian Reader, Mark R. Pettus. Russian Book 1, Russian Through Propaganda, revised edition, Mark Pettus. All independently published.

Although everyone has heard of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Gogol, that is where the general familiarity with Russian literature among Americans tends to end. One may be excused a familiarity with Pushkin: he is one of those poets whose genius is so much one with the genius of the language, that he cannot be translated in a satisfactory way. But Lermontov has been most unjustly neglected.

His novel, A Hero of Our Time, is not only great literature but great fun. An adventure story in the Walter Scott mode, with a hero of the Byronic stamp, it is set in the mountainous Caucasus region in the early nineteenth century, back when Russia was engaged in its sixty-year-long appropriation of the region. For those of us with weak geography, the Caucasus are between the Black and Caspian seas, and includes the mountain range that separates Russia from Turkey and Iran. Lermontov was exiled to military service there in his early twenties, as punishment for a politically ill-considered poem.

Lermontov’s works in the present volume are steeped in the atmosphere, geography and exotic south-west Asian culture of the Caucasus. The perilous adventures he describes are drawn from life. He makes Scott’s adventure stories, excellent as they are, seem, by contrast, exercises in literary artifice. This is the substance, not the shadow. Lermontov wrote while dodging death, whereas Scott wrote while dodging debts.

The Bryronic “hero of our time” and the Demon of this book are parallel literary self-portraits. The satanic protagonists of European literature, from Milton’s Satan to Melmoth the Wanderer are play-actors compared to Lermontov’s creations. Lermontov’s cynical, doomed, passionate, self-mocking characters are closer in spirit to the heroes of “hard-boiled” detective fiction—credible and modern. An ongoing irony of Russian culture is that, looking always to the West for its models, it realized them with a literalism Westerners never considered. One might say that Russia has had the courage of the West’s convictions—typically with somewhat tragic results. Thus it was with Lermontov’s heroes, who are realer than they should be, and his own Romantic attitudes that were so much realer than they ought to have been that they led to death in a duel at the age of twenty-seven.

As for the translation, the particular merits of Pettus’ work may be seen to best advantage in his rendering of the Demon poem, which has only two competitors in English. I will take for comparison the second stanza, which describes the Demon as he wanders through the world.

In 1918 Robert Burness managed,

Outcast so long—no Heaven, no home—

He wandered through earth’s wildernesses—

Monotonous and wearisome,

As one age on another presses,

Or one slow minute follows minute.

The paltry world was his—but in it

His wickedness he wrought resistless,

For men on earth nowhere withstood

His wiles when he essayed—and, listless,

He loathed the evil seeds he strewed.

Truly dreadful. One has no idea of what “Monotonous and wearisome” can refer to, and it is hard not to take it as a comment on the translation itself. And rhyming “minute” with “in it” would be acceptable only in light verse,

In 1979 Charles Johnston offered this version,

He wandered, now long-since outcast;

his desert had no refuge in it;

and one by one the ages passed

as minute follows after minute,

each one monotonously dull.

The world he ruled was void and null,

the ill he sowed in his existence

brought no delight. His technique scored,

he found no traces of resistance—

yet evil left him deeply bored.

Burness can be forgiven the hubris of a translation into rhyme and meter—he was writing, after all, in 1918. But Johnston was being willfully stuffy, encumbering himself with needless difficulties which he failed to surmount. The jarringly slang phrase “His technique scored” is only explicable in a man whose powers of invention could attain no better rhyme for “bored.” His filching of the rhyme “minute” – “in it” is sufficient comment both on his morals and his aesthetics.

With Pettus we breathe at once the air of a better world,

Long since expelled from Heaven, he now roamed

The desert of this world, without repose;

One age after another passed for him

Just as the minutes pass for humankind:

In an unending and unchanging stream.

And in dominion o’er this paltry earth,

He sowed great evil—but without delight.

For nowhere did this artistry of his

Meet with resistance in the hearts of men—

Pettus has opted for blank verse, but the results are unimpeachable. The need to fill out the meter gave him space for added clarity, and Lermontov’s thoughts stand out in clear contour and high relief.

His literal rendering that accompanies the Russian text and vocabulary in Reading Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time and The Demon, is to my mind, even stronger,

Long since cast out, he wandered

In the desert of the world, devoid of shelter;

One age after another raced by,

Like one minute after another,

In monotonous procession.

Wielding his dominion over this paltry earth,

He sowed evil without delight.

But nowhere did this artistry of his

Meet with resistance—

And he grew bored with evil.

This is as close as a non-Russian-speaker will come to the poem itself. In both the literary and word-for-word versions, the elegance and fidelity of Pettus’ rendering is patent. After such a demonstration of ability as regards the poem, there is no need for a comparison with other translations of the novel. Pettus is the definitive translator.

Pettus’ Demon made so powerful an impression on me that I ordered his textbook, Russian Through Propaganda, the first of a series that brings the student through posters and political slogans through literary readings to a mastery of formal as well as conversational Russian. Since we’re cooped up in an limitless lockdown, and the freezer is already filled with home-made breads, why not turn the hours to account by learning the language of Pushkin? There’s a silver lining to every cloud, or Не́ было бы сча́стья, да несча́стье помогло́ as we can now remark with a self-satisfied Cyrillic smirk.

Pettus explains with homely simplicity and scientific clarity matters which other textbooks leave as mysteries (like how to pronounce the “soft” consonants). He immediately introduces real Russian though vintage propaganda posters, which are visually interesting, and range from the brilliant designs of Rodchenko to the kitsch of Soviet Realism. Conventional language textbooks rarely progress beyond such marvels as asking for directions and telling time. Here, the thrill of first-hand insight into another culture is delivered immediately in short sharp bursts through Soviet slogans, which are often as not both unintentionally hilarious and deeply revealing.

Russian Through Propaganda is accompanied by free online videos that explain each lesson in detail and give language-lab practice in usage and pronunciation. Pettus’ humor, directness and practical advice make this a pleasure as much as an education.

The Villagers, Art by Caroline Golden, Fables by Derek Owens. Animal Heart Press, 2022.

Derek Owens and Caroline Golden need no introduction to readers of 96th of October. Their work, both from this book and that they have created since, has become a prized feature of this magazine. This is a beautifully produced hardcover book, with full-color reproductions of the collage illustrations accompanying each of the tales. The best foretaste of this elegant volume will gained by following this link to Owens’ stories here. Beyond that, I can hardly improve on Jacob Rabinowitz’ blurb,

“Derek Owens constitutes an intractable independency which you may find on the map of the imagination somewhere between the Duchy of Donald Barthelme and the Principality of Jorge Luis Borges. As is the case with Vatican City (its closest match in size and rare book holdings), the currency of Owens depends on the economics of belief. Geographically, Owens is less a riparian land than an outright lagoon, with a range of fauna that call to mind an earlier, more innocent, and less inhibited age of map ornamentation. Logical instability makes this a less safe destination for the casual visitor. It has long been regarded as a region of mystery, a reputation which this collection will do little to diminish.

“One’s passage through these landscapes has been rendered yet more hallucinatory by the collages of Caroline Golden, who has done for Owens what Magritte did for Belgium. Her portrait-like images are at once cozy and disquieting, playful and grotesque, like a set of Toby Jugs acquired as souvenirs on a holiday in the world of the dead.”