Purgatorio

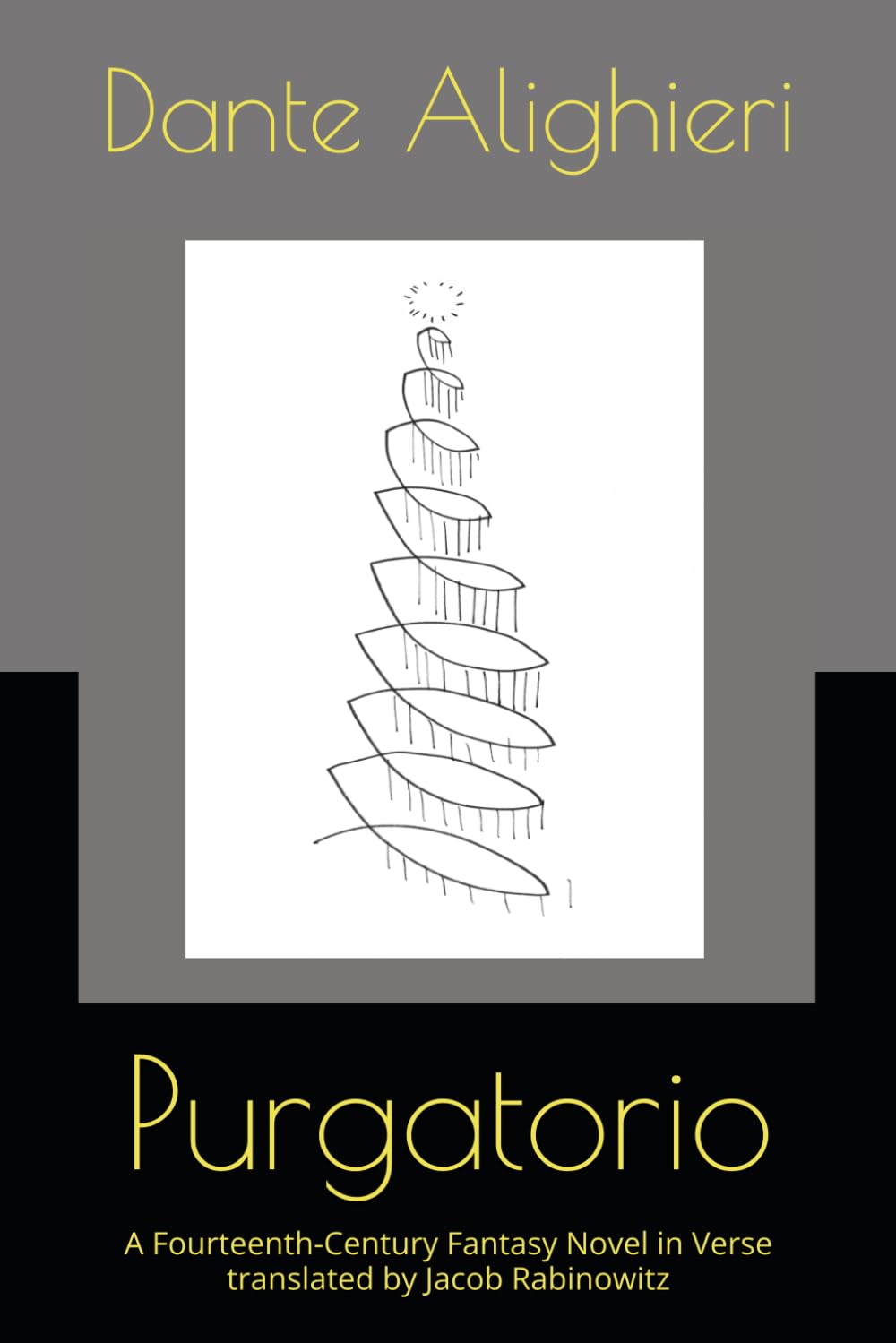

An accurate translation of the Purgatorio with all notes and clarifications poetically woven into the text so as to permit an immediate reading with full understanding, instead of a scavenger-hunt through the footnotes. This new edition contains copious maps and genealogies to clarify the history, geography, astronomy and cosmology.

from canto XXIII

with my gaze I tunneled in among

those green leaves, like one of those who waste

their lives hunting birds, supposing bow-sport

to be a noble pastime,

he who was more than a father to me

said, “Child of mine, come along, our allotted

time asks a wiser division of the minutes:

we’ve given enough to this.”

I turned my face from the upward foliage

and followed fast after those sages

whose overheard conversation

made all my going seem easy and free.

Suddenly we stopped, hearing

in melodious moans the words of the Miserere,

(the Fiftieth Psalm), “O Lord, open thou

my lips . . .” the voices were pregnant

with pleasure and with pain.

“Sweet teacher,” I began, “what’s this I hear?”

He answered, “Probably souls

untying the knot of their obligations,

paying slowly what they owe.”

Just as pensive pilgrims on their path,

when they meet strangers, if they notice them at all,

only turn to give a moment’s attention,

neither thoughts nor eyes long resting

on whom they meet, they pass unpausing on:

other cares are theirs,

thus a crowd of souls, moving faster than we,

came from behind, marveled at us for a moment,

then passed ahead, silent and devout.

Dark and hollow were the eyes of all,

pale was their skin, their bodies so thin

and diminished that their bones alone

gave taut shape to their stretched and tented hides.

Once upon a time Erysichthon,

impious prince of Thessaly,

cut down a grove sacred to Ceres,

goddess of harvest. He was punished

with such hunger he devoured all he had, consumed

his holdings to pay for more provisions,

but only got skinnier the more he ate,

starving even as he gorged.

Finally he chewed the thin sinews

from his own bones. He ate himself to death.

Not even Erysichthon, diminished to a sliver

of himself, insanely fearing hunger’s pang

more than the taste of death —

not even Erysichthon,

when his fatal desiccation had reduced him absolutely

was so dried a rind

as these shrunk souls.

I thought to myself, “This is how the Hebrews

must have looked in the final days

of the Roman siege of Jerusalem.”

Then, we’re told, a mother, her face

starved sharp as a beak, pecked the flesh

of her own cooked child. The starving partisans

who came upon her grimly feasting,

to whom she offered a portion, fled in terror.

I thought of that inhumanly hungry mother

as I gazed upon these withered spirits,

eyes like rings that have lost their gems,

empty bezels, sunless orbits.

Some say the Latin word for “human,”

homo, stands out on the skull,

printed in ridges, embossified.

The silent “H” isn’t shown,

but the brow and the nose bone form the M

between two eye-socket O’s.

Well, across these faces the name of Man

was labeled large in skull-bone font,

its mortal meaning all too plain.

Who could believe the mere scent of fruit,

the smell of water, could so control a soul

as to shrink and shrivel it

with disembodied longing?

Who could guess the impossible cause?

For now I stayed astounded

to learn that spirits could dwindle,

not fathoming the meager reason

for their shrunken shapes and scaly skin.

Suddenly one of those ghosts

stared intently at me from the deeps

of its eye-pits, then shouted, “What a favor,

meeting you here!”

I’d never have recognized his face,

for that was mostly gone,

but the voice revealed at once in full

all the lost identity.

The single spark of recognition

blown to life by a vocal tone

sufficed to make old memory blaze

and I saw in his ashen mask

and lipless visage the face of my friend Forese.

He said, “Don’t look at the wasted, flaking flesh,

the blotchy scabs, the dull dead hue

of my dried-out hide, the lacking fat,

the death of me —

but tell me true of you,

and of these two escorting souls besides.

Pray, stay, and say what story’s yours!”

I answered, “I already wept once

to look on your dead face;

now I cry for you again, no less,

to see you so distorted.

I can’t yet talk, wonder still stuns me,

gaping takes my words away.

You tell me first, in the name of God,

what abrades your parched armature

flake by flake?”

Forese said, “God’s eternal wisdom

placed in the water and the plant you just passed

the power to make us wane with wanting them.

The whole nation here, tearfully singing,

restore themselves to holy health

through hunger and thirst, for they followed food

and drink, never knowing what was enough.

We’re consumed, as if by fire,

just by thinking only and ever

how much we want to eat and drink,

fascinated by the fragrance of water,

the bouquet of the fruit

wafting down through the branches.

That wasn’t the only such tree along

the circling way, that forever refreshes

our torment as we pass.

There’s always another ahead to renew

our pain — do I say pain?

I should rather call it comfort!

We approach these trees with the same deliberate

good will with which Christ went to his cross.

He felt a subtle unearthly gladness

even as he cried out, “God, my God,

why have you forsaken me?”

He knew a grim and hidden satisfaction

as he bought our freedom with the blood in his veins.”