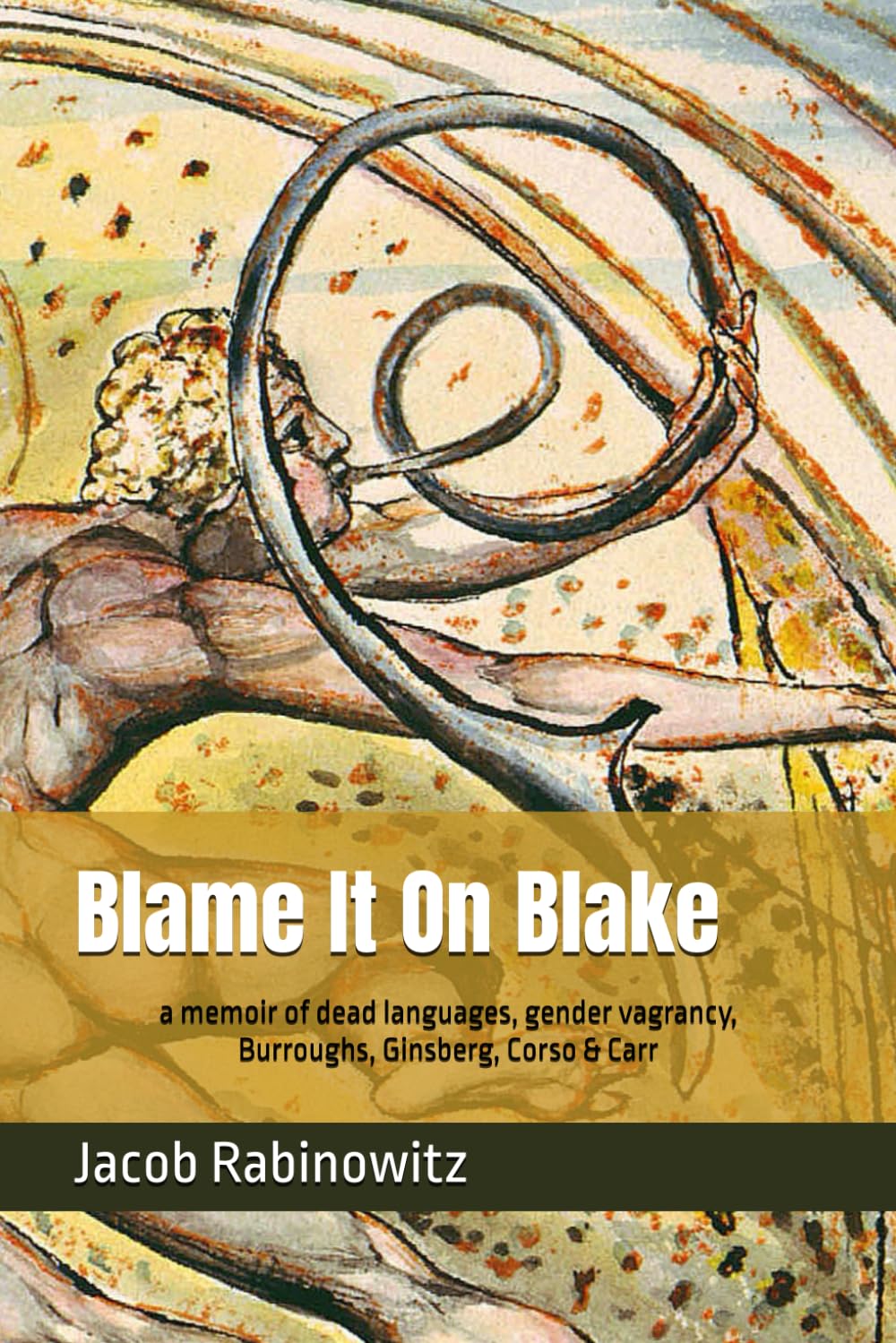

Blame it on Blake

A memoir of Beat generation authors, with explorations of Witchcraft, Egyptology, Voodoo, gender confusion and mind-altering drugs, authorized (more or less) by William Blake.

excerpt from the book

Allen introduced me to his circle. Of greatest interest to me was William Burroughs, whose writings I absolutely venerated. A tall, spare, cadaverous man in a well-cut suit which he unfortunately often wore with an embroidered Moroccan vest, his dignified demeanor and laconic speech made him seem imposing, mysterious and deep. The science-fiction themes of his writing added a further layer of glamour. It was easy to imagine him possessing a non-human intelligence, or diplomatically representing a trust of giant insects from another dimension. That would account for the studied, judge-like repose of his features. Rarely did he smile, never did he raise his voice.

The provincialism of New Yorkers! Bill was merely true to his midwestern type, a slow-talking Missouri man, measured in his words, skeptical and unforthcoming, most at ease looking out over his land with a rifle in the crook of his arm, or sipping bourbon on the porch come evening. Look at the map, and ponder the psychic geography of Missouri, right between Kentucky and Kansas, and you’ll understand a lot about Burroughs, and for that matter, about his modernist countrymen T. S. Eliot and Donald Judd.

At that time, Burroughs was living in a loft on Prince Street, at the top of a dizzying flight of stairs. The space was a vast semi-finished rectangle, with the bed at one end, at the street-facing window, the kitchen at the other. There was little by way of furniture. A few chairs, a desk for writing, a small coffee table. It would have qualified as spartan, were it not for the cases of vodka that lined the walls nearly all the way around. He had taken payment for some lecture or writing project not in cash but in booze, and he drank his way through it in a little over a year.

He had an orgone accumulator, a metal-lined wood box big enough to sit in comfortably. According to its inventor, Wilhelm Reich, remaining in it enabled one to build up a charge of orgasmic psychic energy. I never saw Bill use it; I think he occasionally occupied it to smoke a joint and rev his head for writing. His very modest array of bookshelves were slenderly stocked: most prominent were the writings of Carlos Castaneda.

After querying Allen to be sure he wouldn’t be jealous if I slept with Bill, I did so. The first time was an evening when I was a dinner-guest. I just kind of stayed after everyone else left. We drank his vodka, smoked some grass, and woozily migrated to the bedroom portion of the loft. He sat on the bed, I sat on the chair. We studied each other. Actually, he studied me. I was pretty high and just zoning in and out.

“We are having a confront,” he pronounced deliberately.

“Uh-huh,” I riposted. A long pause followed.

“You don’t think I’m . . .” his voice trailed off, then returned, “. . . too old?”

“Nope,” I lied, and unbuttoned my shirt.

Needless to say, I was welcome at the loft from then on.

Like Bill, I smoked. He favored Senior Service, a rich Virginia tobacco non-filter British cigarette, comparable to the more readily available Players. He must have developed a taste for them while living in England, where they were common and classy enough for Ian Fleming to put a pack in the pocket of James Bond. I smoked Gauloise, liking the darker Turkish and Syrian leaves which gave it a slightly harsh taste and very distinctive smell. The point here is that I smoked like a Parisian cab driver, enthusiastically put away serious amounts of alcohol without discernible effect, smoked grass, was seventeen, had hair down to my shoulders and needed a shave about once a week. I wrote poetry using the cut-up technique and had practically memorized great swatches of Bill’s writing. Bill and I were fairly compatible.

Bill would typically spend the day smoking joints in front of his typewriter, tapping away at whatever book or essay he had in hand. He was a tireless full-time writer, a real professional. I made sure to be on my way before he started his day’s work, for he liked to be undisturbed, alone at his desk in a cloud of reefer in the big empty space of his loft. And that is an apt emblem of his extremely solitary life, a big empty space between himself and other people, cozy with the constant influx of anesthetics, in the company of the fantasy characters he typed into existence. Come evening he’d cook dinner. He tended to make spicy Moroccan-style stews, and he liked having company over. There’d be plenty of drinking. He held his booze well. He knew how to pace himself, and I never heard him slur. He was a great raconteur, and whenever he had guests to table he’d regularly set the room in a roar with his stories. I wish I could recall any, but this was forty years ago and I was drunk at the time, so those pretty verbal birds have long since flown.

When I met him in 1975, he was sixty-one. The relentless drinking and reefer made him emotionally undemanding, and his natural charm made him easy to be with.

I remember standing in his loft one afternoon, a glass of vodka in my hand, thinking to myself in triumph, “I’m here, I’m in William Burroughs’ loft! I’ve finally arrived!” And that was pretty much the height of my ambition. I wanted to be with people like him, not people who would be in awe of my abilities, but people for whom my talents, interests and proclivities would pass unremarked, be simply accepted.

Bill and I didn’t talk about literature or lofty topics. He thought Castaneda offered genuinely valuable insights into life and magic and metaphysics. He devoured Science Fiction “for the ideas.” I once asked him how he could read this kind of thing. He asked me what I reading matter I would suggest instead.

“I don’t know. Homer? Chretien de Troyes?”

“You are,” he said with a weary shaking of his head, “so chi chi.”

The expression, which even then only survived in the periphery of gay culture, means “ostentatiously stylish, overly concerned with being chic.” To translate for the heterosexual reader, Bill was suggesting that my literary judgments were on a level with one girl sniping at another for carrying last year’s purse.

Ideas and literature were not good topics. He was, however, interested in noise. He often remarked on the incessant barking of dog to dog across the blocks in NYC, which you heard all night in summer when the windows stayed open (no one air conditioned a loft).

Another din of interest was the sound of the radiator. Bill had an old one in his Prince street loft that lustily clanked and banged. “Sounds like two dinosaurs fucking,” he said. “If I taped an hour of that and mixed it I’d make you a symphony that would not quit.”

Bill’s implicit disdain for modern music was matched by his disdain for modern art, which later translated into the paintings he created by shooting cans of paint in front of canvases