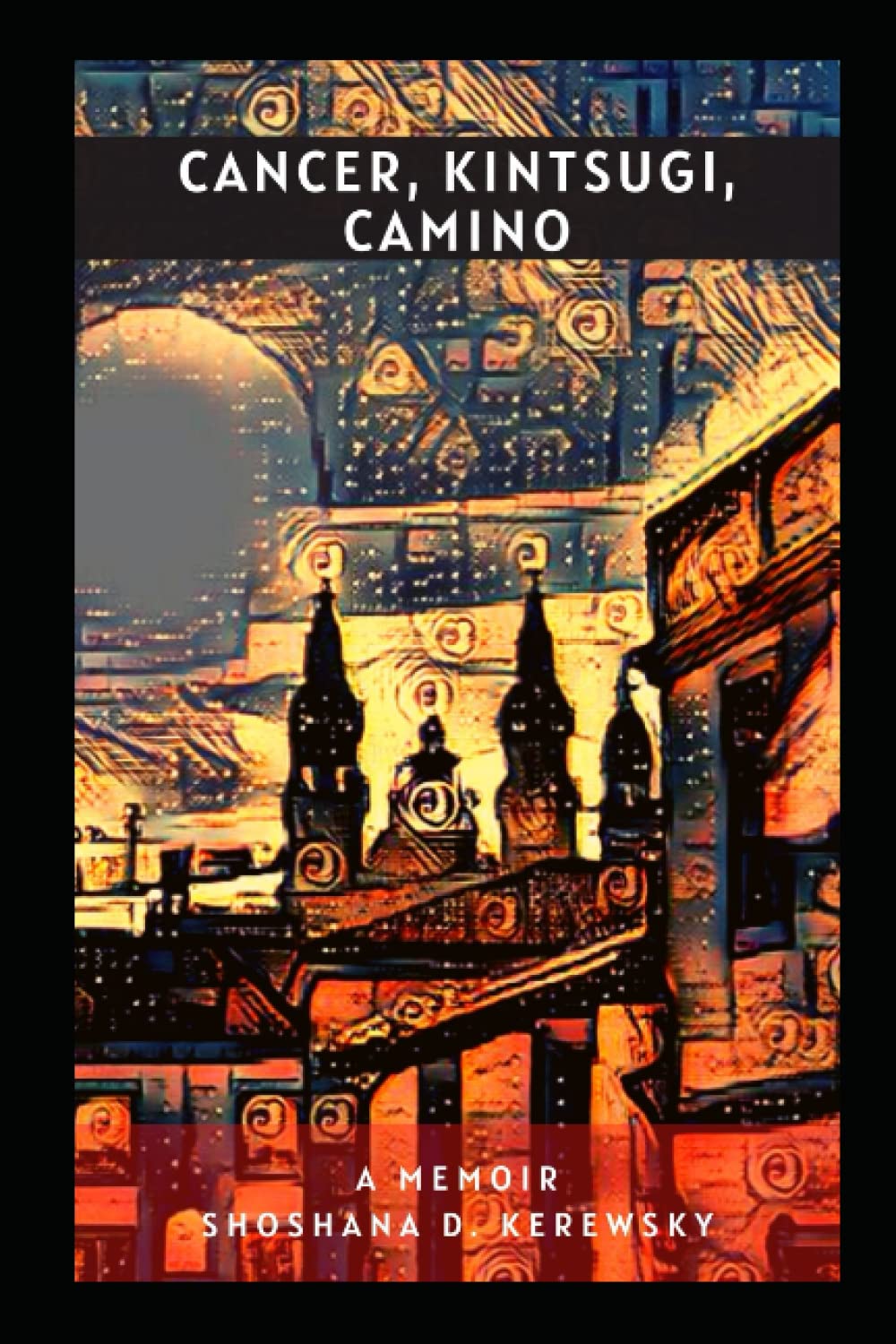

Cancer, Kintsugi, Camino

Not just a memoir of breast cancer and the Camino de Santiago. It’s also about Jewish identity, atheism, family, AIDS, COVID, metaphors and similes, breathing, bricolage, journeys, self-reflection, and hypothetical cuckoos. Through richly-layered fragments of lyrical prose and poetry, the author conveys the rhythms of thought, feeling, and walking in a sparkling narrative mosaic.

excerpt from the book

The linear accelerator rotates to roast my flesh. Rotisserie chicken, dark meat only. Someday, I will leap up and dance.

I don’t presume that I have a right not to die, though I’m aware of a strong substrate of this underlying assumption.

I fear tamoxifen’s long list of side effects. I had learned a medicine-taking strategy from a video about AIDS and psychology: Associate the pills with prayer or thanks, so every morning I meet its blank white gaze, an eye in my palm to ward off danger, and address it, “Thank you, Tamoxifen” before I swallow.

Am I a double Amazon, or Tiresias? An undouble-breasted cormorant?

Cancer untruths I have encountered:

• Cancer will kill you.

• If you eat right, you won’t get cancer.

• This treatment cures cancer.

• This unattested, anecdotally-reported treatment is better than those poisons.

• Big Pharma just wants to steal your money.

• If you’re good with God, you won’t get cancer.

• Thinking negatively makes the cancer kill you.

• If you got cancer, you haven’t worked through your

• anger issues.

• You did something bad, and cancer is the punishment.

• If you say the word “cancer,” cancer will sniff you out and hunt you down.

• If you skip medical visits, they won’t find cancer so you won’t have cancer.

• You’re better off dying than having your body change in gendered ways.

• Biopsies don’t hurt.

• You’ll be up and around in no time!

• This will only be slightly uncomfortable.

• If you have a good cancer, it won’t kill you.

The myths are signs, encapsulated guideposts. They hold a story but aren’t the only story, or the experience.

I dreamed in the early morning that I looked down at my body and had had my mastectomies. I was wearing a cravat or kerchief but my torso was otherwise bare. I had some feeling of loss or diminution, but this was secondary. I was focused on the dream’s action. This was the first dream in which I saw my chest; surgery was 10 months ago.

I dreamed I was in the pleasant waiting room of a medical practice talking with a woman, a fellow patient but with different issues. She put both hands on my breasts to see what they were like, then became flustered. I was startled but took my shirt off so she could see. I had nipples and small breast swellings, which concerned me. I made a mental note to discuss this at my oncology appointment. The woman then pulled on a crepey-ropy veil of flesh hanging from my right chest and axilla to about my knee. She commented that “It’s supposed to snap?” I felt the skin to assess it. I had some pain and sensation closer to my chest, but wondered if I could trim it back without bleeding too much. I wasn’t too upset; my response was, “Oh, another goddamn thing.”

I dreamed I was lying on a gurney in a hospital corridor, all of my clothes off and other people walking around. The sheet was pulled down, showing my mastectomy scars. I wasn’t there for a procedure or action that had anything to do with mastectomy.

I have achieved a hard-core punk look with my drastic and emblematic hair, my body mod, my tattoos, my sunken eyes and cheeks. Or else clergy: My tonsure, my mortification of the flesh, every shirt a hair shirt, skin formicating with imaginary insects.

It’s not turtles all the way down. I am going to die, and I don’t like that. Bury me with terra cotta, my warriors of Xi’an.

My body still looks like a portrait by Egon Schiele, proportions distorted, puffy, skin the color of old bruises, hollowed orbits, lumps. My armpits and chest are asymmetrical. I am shaded yellow-green beneath the skin. I chose this; I am still my body.

A year ago, I was in pre-op. I count today as my cancerversary because rather than inscribe the distressing diagnostic events in memory, I want to celebrate the surgery that is what I believe eradicated the cancer. Chemo and radiation were the frosting on the cake, and tamoxifen, I guess, the sprinkles or something. The metaphor really breaks down here. Itemizing my medical visits for the last year highlights how much work this has been, and continues to be.

It is wonderful to be back to birding and seeing different countries, and as a bonus, my now-constant vertigo and my motion sickness cancel each other out so I have no nausea at sea. In Cuba we visit Fusterlandia, a Havana neighborhood rendered psychedelic, hallucinatory, encrusted with mosaic and bricolage. I feel sympathy for the raw edges, the crude joins that do not try to disguise or beautify the transitions.

Frederic died 22 years ago. That bastard. He skipped out on all of this. I light a yahrzeit candle a day early since I need to leave at 4:00 AM for my annual test item engineering gig. On the flight I try a set of Juzo compression sleeves and gauntlets. The set I first got itch and leave a waffle pattern on my arms. People smile at me in the Salt Lake airport, perhaps because my shirt is pink, perhaps because of the sleeves, perhaps because I am walking with a cane, or perhaps because there was a memo to all Saints to smile at visitors. The state I’m flying to has just passed an anti-trans bathroom bill, increasing instances of less-feminine women being harassed and pursued when they try to use the restroom. I have short hair and no breasts. Nancy exacts a promise that when my team eats at a restaurant, I won’t try to pee unaccompanied.